At The Celebration For Reynolds Price At Duke

At The Celebration For Reynolds Price At Duke

by Ben Cohen

One evening last spring, exactly one year ago tomorrow, I drove with a few friends through the quiet woods of North Carolina to eat dinner with the writer Reynolds Price. “Please don’t have any plans that will rush you away immediately after the last bite of food,” he warned beforehand in an email. We had just completed a class with Reynolds, what would turn out to be his final course, meeting Tuesdays and Thursdays around a rectangular table in a room overlooking a parking lot, to discuss The Gospels. This night felt no different than those classes, with Reynolds telling us stories about the friends he knew very well and the people he’d met only in passing.

“Have I ever told you my Bob Dylan story?” he said once at the beginning of class. (Could there be a better way to begin a class?) Reynolds had seen Dylan at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. In that same 75-minute session, he told us about his run-ins with Jimi Hendrix and Shaquille O’Neal before proceeding to read aloud from the Gospel of John. By then, his baritone wasn’t so booming — his voice had once been so musical that when he recited passages like, “Before Abraham was, I am,” it must have been nothing short of the sound of God — yet class still consisted mainly of him reading his translations as we hung on his every word. We dutifully scribbled his textual insights and then littered our notebook’s margins with everything else he said. Each conversation brought a new quip. Perhaps someone would ask him about Lady Gaga (“I like her name!”), or he might tell a story about seeing Bill Gates (“a piece of chalk with a suit on him”).

He could tweak both academia (“A great many modern scholars don’t agree with that, but a great many modern scholars are assholes”) and then roll his eyes, as always, at the mention of Twitter (“What a way to spend a life!”).

At the end of the dinner, when the sun was finally down, we took our ice cream and sat in the living room between walls that could have furnished museums. (Reynolds’ art-buying habit was so prodigious, a local gallery owner once tried to cut him off, like a bartender refusing to serve someone more drinks, because he had no room left in his house. That was in the 1980s.) Not long afterward, all of us recognized that it was time to leave. He turned to us, obliging, and offered one last snippet of what he dubbed grandfatherly wisdom. It was concise enough that I could commit it to memory even after two hours of red wine. “Never do something you don’t love for more than three years,” he said.

I was reminded of this night in January, when Reynolds died at the age of 77, and again yesterday, when about 300 people gathered in the Duke Chapel for a celebration in his honor. The event was called “A Long and Happy Life.”

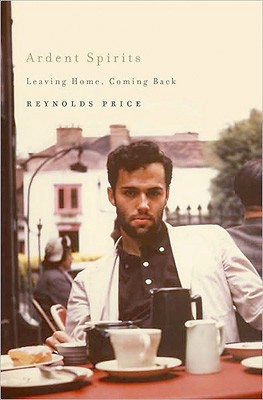

That was the title of Price’s first novel, which he published in 1962. He was just seven years removed from his undergraduate days, when he’d forged such a legacy at Duke that the legend of him dashing through campus in a scarlet-lined black cape still persists. He left his alma mater only to spend three years in Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship — Duke’s president, an English professor himself, described this period yesterday as his “truancy” — before he returned on an appointment to teach freshmen. It was meant to last three years. He turned it into 52.

Reynolds did not want a funeral, and this commemorative service lasted only an hour, right around the time limit he’d stipulated: “In my lifelong dread of boring the world, I want nothing that lasts longer than 45 minutes.” The ceremony started with a 2001 recording of Reynolds reciting ten lines from Ben Jonson’s “To the Immortal Memory, and Friendship of that Noble Pair Sir Lucius Cary, and Sir Henry Morison.” His voice glided through the chapel before making way for five speeches, a poetry reading and a scene from his play “August Snow.” One of those speakers was the writer and producer Daniel Voll, the first of 30 men who Reynolds hired for assistance after a spinal tumor, discovered in 1984, left him paralyzed from the waist down. (He frequently referred to this job, a one-year stint, as the Reynolds Price Finishing School for Husbands.)

“Reynolds was gracious enough to let us think we had something in common with him,” Voll said. He paused. Then he acknowledged what that implied: we didn’t, and we couldn’t.

It was true, maybe especially so, for people who met him only last year. This was partly because he was the teacher anyone with a certain bent sought out before graduation — as Voll said, if you wanted to be a writer at Duke, someone would tap you on the shoulder and tell you to find Reynolds Price — and also because he indulged in the sort of culture that other serious novelists dismiss while hibernating in their garrets. I learned just yesterday, and it somehow wasn’t all that surprising, that Reynolds delighted in scouring eBay. The same man who snacked on pimento-cheese sandwiches (from Ava Gardner’s recipe!) with Harper Lee also owned an Eminem bobblehead. He danced with Lauren Bacall many years before he was driven in a specially designed minivan to see “Twilight.” Once, before a poetry reading, he asked someone to pose a specific three-part question to ward off that cruel silence between applause and the question-and-answer session. This friend agreed, memorized the question, and, when the time was right, repeated the query verbatim. Reynolds simply stared and informed him that this was the dumbest question he had ever heard. He aspired to be the most memorable American writer of his time, and he also loved Fast Times at Ridgemont High. How could such a person exist? Even his oldest friends in the front rows — the gray-haired folks who knew him in the 1930s, 1960s and 1980s, who spent more than just a few afternoons in his quiet home, who have read and re-read his published volumes of fiction, poetry, plays, essays, short stories, memoirs and translations — hailed him as a veritable icon, a type that won’t be around much longer, a legend in any right.

The ceremony concluded with a recording of James Taylor’s “Copperline,” lyrics by Reynolds Price, and before everyone could file out into the cloudless afternoon to gather in the library to nosh on miniature biscuits and deviled eggs, the song filled the chapel with such sweet thunder that it made me recall something Reynolds had said just about three years ago, when a similar group of luminaries gathered for a weekend event called “A Jubilee for Reynolds Price.” The first night coincided with a basketball game on campus — you know, of course, why I remember this — and not a five minute’s walk away, Reynolds was talking at an oak table with his friend Charlie Rose, who was in town to interview him for the occasion. He had just turned 75. It was 50th year teaching. “What a good time I’ve had,” he said. “You’ve never met someone who has enjoyed life as much as I have.”

Ben Cohen writes about sports at the Wall Street Journal.