'Repo Games': Turning Poverty Into A Game Show

The insider term for the goal of those who produce reality television shows, those who assemble the footage into episodes, is a profane one. I learned this from a reality television producer (who wished not to be named so as to continue being a reality TV producer). “We in reality TV talk about ‘shit to gold,’” RTP said. This is the mechanism by which some soul is given an opportunity to overcome an obstacle. “The audience loves seeing shit turn into gold.” Objectively speaking, they certainly do.

I was talking to RTP about this peculiar little program called “Repo Games.” The show is, naturally, about repos. Home foreclosures may hog the headlines, but little tiny foreclosures, or ‘automobile repossessions’ are a quieter reality of these modern times. In 2009, 1.9 million cars were seized for loan non-payment. More than 5,000 vehicles a day were repossessed, 5,000 sad little transactions that make no one happy. So what could be more American and more now than producing and broadcasting a game show in which debtors fight to save their potentially repo’ed vehicle by winning a trivia quiz, for our home-viewing edification? A show like that could be called morally questionable. It also could be called Tuesdays at 8 pm on Spike TV.

I’ve watched the three episodes that have broadcast at the time of writing this, and the show is primarily nothing but disturbing. It’s produced well — the cameras don’t shake, you can hear clearly everything anyone says — but it’s an experience that requires a number of actual showers to make you feel clean.

The premise is that a repo man, in the course of his actual job, will casually mention to the loan defaulter, once the vehicle is chained to the tow truck, that if they play a little game, and they can answer three out of five trivia questions, then they can keep the car and the loan will be paid off. That sounds like an excellent opportunity for the defaulter. In fact, on paper it is an excellent opportunity. The trivia questions aren’t that hard. There’s usually one of the five that’s a bit tricky, but never an impossible question, like something about the Jewish calendar or the middle names of the partly-famous. It seems a small price to pay for having an auto loan in default paid off.

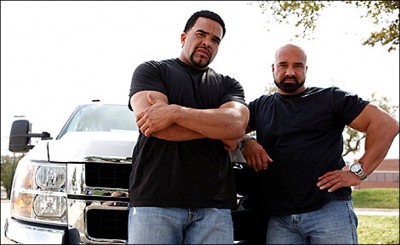

Actually, it’s a very big price: being broadcast to millions of potential television viewers as someone in financial peril, plus also possibly someone who is not very good at trivia. Not to spoil anything, but four of nine “contestants” on the shows I watched did not manage to win the Repo Game. The answers from the losers were embarrassing (as are some of the wrong answers from the winners), and enough so that repeating them would make this piece an accessory to the crime. The actual repo men, however, are the protagonists. They’re big fellows, but with gentle, been-around-the-block affability. They’re the good cops, and they manage to explain the game and read the questions. Yet what charisma the repo men may have is not enough to elevate this show into anything but a tawdry little twenty-two minutes.

The kneejerk response to the questionable is to ignore it. “This is the worst thing ever, try it,” is a request to which no one looks forward. The logic behind this is that by choking off reference to the toxic crap, interest wanes and the toxic crap is soon totally forgotten. But this toxic crap is particularly timely. We live in what continues to be a recession. No matter how the GDP may slowly rise and how many bulls roam Wall Streets, the people aren’t feeling it. A big swath of the Baby Boomers are becoming personally acquainted with permanent unemployment, and a commodities spike has transformed the visit to the grocery or to the pump into a potential cardiac event. Times are tough in a way that times have not been tough in generations. Because of this, “Repo Games” is potentially trenchant toxic crap, as it distills all of the uncertainty and dismal prospects of the era in which we live into a calorie-free nothing of a cheap reality show. It turns the heartbreaking into the banal. It’s fascinating, like a package in a train station that makes a sound that could be ticking if you cock your head the right way.

***

Jennifer Pozner is a media critic and journalist, and the author of Reality Bites Back: The Troubling Truth About Guilty Pleasure TV. Her premise is that reality TV is not a popular form that was borne of consumer demand, but rather a business model that became ubiquitous as its comparatively low production costs (and correlating high profit margins) became evident to the rest of the industry. And the appeal of these shows? She told me: “Reality TV is intentionally steeped in social beliefs — deep-seated biases about gender, race and class — that regress viewers to the intellectual state they had when they were three or four years old.” The moral landscape of reality TV is black and white and without any complexity at all. Repossessees are looked down on because they are bad, solely by virtue of being a repossessee in the first place. And these broad strokes, the reduction of the world into the ethical structure of the playground, is, according to Pozner, the intent of the producers of reality TV.

When I struck up the conversation with the producer RTP, who has worked in the field and in the editing room on shows both similar and dissimilar to “Repo Games,” I asked right off, “Is there such a thing as a moral responsibility when producing reality shows?”

“Hmm,” said RTP, and then paused. “I think my pause says a lot.” It did. RTP emphasized that these shows were vetted by lawyers and Standards & Practices offices of the networks. But, I asked, is there ever a line that’s crossed? RTP answered, “Absolutely. You’re exploiting people’s misfortune, bad decisions, etc., for entertainment purposes. It felt gross. But it was case by case.”

This brings us back to the Philosopher’s Stone of the industry, “shit into gold.” Every debtor that trivias his or her way out of their auto loan, and even every chance to do so, is a narrative with an upward trajectory. RTP added, “Also, if the debtor guesses wrong and they lose the vehicle, well, fuck ’em. They couldn’t pay anyway, so the audience doesn’t have to feel bad for ’em. And if they do win, then the audience can cheer for ’em. The audience wins either way.” On a basic level, Pozner and RTP agree: Reality TV is engineered to draw us in by constructing these narratives that punch lizard-brain buttons: empathy, contempt, jealousy.

And who are these people that we feel bad for? Their depiction is the most upsetting aspect of the venture. Signifiers of lower economic class status are abundant on the show. There are the too-many-babies, there are the less-than-clean domiciles, and there are slack-jawed vacant stares. It’s a vicious stereotype that doesn’t so much cross the line as it does run over the line with a lawnmower. It’s a field guide for the slanders used by those that believe that debt, poverty and bad circumstance are always the result of bad decisions and poor breeding.

I’m not saying that the events portrayed didn’t happen, or that these stereotypes don’t exist for a reason. But the subjects for each episode are not chosen out of a hat, and footage does not air unedited. The tone is a choice, and the tone is “poverty porn.”

I asked RTP if the subjects of the shows RTP has worked on that deal with similar socio-economic issues as “Repo Games” are ever reluctant to appear. “Always,” was the answer. This may be the reason that, if you hang around until the end of the end credits of each episode, you’ll see a very small-print disclaimer stating that those that appear on the show receive an appearance fee.

This is not to excuse the defaulters. But we the viewers are never acquainted with the whys and wherefores of the reasons behind the fiscal crisis of each “contestant.” Are they Livers-Beyond-One’s-Means, or are they Actually Unfortunate, a victim of an unexpected job termination or sustained medical emergency? Ultimately, it doesn’t matter, at least to the show, as the show presents a little America where no personal financial story is tragic and all defaulters are dirtbags by default.

And the heroes of the show, the Repo Dudes, are not immune from this. They cannot avoid the subtle eyeroll or the resigned condescension when commiserating with the eventually repossessed. The Repo Dudes are not the authors of this, but they do not transcend it. A conversation-ender used by one of them is, “Why didn’t you pay your bills?” The Repo Dudes have bought into whatever ingrained caricature of our debt culture that enables an actual TV show to poke the less fortunate with sticks just to giggle at their comical protestations.

Let’s go back to the conversation-ender, “Why don’t you pay your bills?” Let’s take as a given that it’s a question that at all deserves to be asked (though some would argue it isn’t). But if it is, it’s also a question that deserves the opportunity to be answered, and a peek into the lives of the scorned defaulters of America, a peek that is not just pornographic but near-bukkakic, is not a valid opportunity to do that.

***

“Repo Games” is not the sole repo-themed basic cable enterprise, nor is it the first. If you’ve spent time in the triple digits of your cable provider you may have noticed “Operation Repo,” “Repossessed!,” “Wild Animal Repo,” “Night Shift: Repo Men” and even “Airplane Repo.” Some of these shows are straight documentary, and some are dramatic recreations (think anything hosted by Bill Kurtis). They all deal with the potentially sticky question of finding entertainment in the default of debtors, so maybe the horse already out of the barn when it comes to this particular topic. But “Repo Games” is not just an exercise in voyeurism. It’s a game show, and a whole ‘nother nested level of comment on the phenomenon of people having their stuff taken away.

The industry itself is not a fan, even though the repo men are clearly the stars of the show. “The program clearly depicts the recovery business as a group of unprofessional, unlicensed, lawbreakers,” says Les McCook, the Executive Director of the American Recovery Association, a major trade association for the recovery industry. “The number one thing the show gets wrong is the violations of the debtors rights in almost every scene,” says McCook. It may sound incongruous for a trade association to worry about the rights of its non-customers, but asset recovery is a very delicate job. “If the television show were to portray the recovery industry as it really is, it would not have a viable television program. Most collateral recoveries are conducted quickly and quietly,” says McCook.

Sadly, it’s not the quick and quiet repos that make the news. Just in recent weeks, a repo in Saline County, MO ended in assault and a trip to the hospital, two repo men were run over in Kentucky, and a Nevada gentlemen mistook the intentions of a “Repo Games” crew themselves, which started with a punch in the face and then ended with an armed standoff with the North Las Vegas police department. None of these incidents ended in the loss of life, but that is not an entirely unheard of outcome.

That’s some gritty stuff, above and beyond the drama of men and women doing the dirty job of collateral repossession and the “clients” who do not love them. Possibly the stuff of art — mention must be made of course of Repo Man (and its sequel?) — but is the repo industry something on which to base a game show?

Those in the repossessions industry just want to get their jobs done, without any undue attention and most of all without any trouble. The ideal repo intends to have absolutely no contact with the debtor until the job is completed. Repo men do not knock on doors and ask the motorist to watch while their ride is snatched. The drama, the hurt feelings and the obstreperousness of the repossesses are exactly what the industry is trying to avoid, and that is exactly the aspect of the industry that “Repo Games” is popularizing. This is why the ARA is displeased. Says McCook, “The public that watches these programs now believe this is how they will be treated if they have the unfortunate occasion to deal with a professional recovery agent. Part of the reason we have seen an uptick in violence is that this expectation of mistreatment has created an acrimonious relationship between debtor and agent before the agent has ever had contact with the customer.”

“Repo Games” takes these transactions and yanks them out of context. It’s not by accident. In the name of creating a product that will garner eyeballs, defaulting debtors are lured out of their homes and in front of a camera so that viewers at home can alternately feel like there’s a chance out there because that lady got her auto loan forgiven while simultaneously congratulating themselves on the happy fact that they don’t have it as bad as those poor goofs.

***

Terrible as it is, “Repo Games” catches the extant texture of American life, almost as if it had been imagined as parody, as the punchline of a in-joke between TV executives — “What about a show in which [abhorrent thing happens and is filmed]? Right?” Right. (I asked Pozner about the advent of “Repo Games”: “It’s not surprising to me. I almost expected this about three years ago, as the economic conditions became evident, a new subgenre of reality TV that plays on the pathos of poverty.”) Maybe Bumfights started out in a similar way, back when society was less frayed by economic insecurity and could preoccupy itself with bald meanness. Though, for the record, Bumfights never made it to a broadcast medium, like “Repo Games”.

It’s no small coincidence that, fifty years ago this week, the head of the Federal Communications Commission, Newton Minow, gave a speech to the National Association of Broadcasters. Minow gave notice to the networks of America that the FCC was going to turn an eye to the quality of content on the airwaves, after a period of quiz show and payola scandals and general programming insipidness. It was a really good speech, and it coined the phrase “vast wasteland” (although the phrase that Minow hoped would stick was “the public interest”). It’s worth quoting now:

Why is so much of television so bad? I’ve heard many answers: demands of your advertisers; competition for ever higher ratings; the need always to attract a mass audience; the high cost of television programs; the insatiable appetite for programming material. These are some of the reasons. Unquestionably, these are tough problems not susceptible to easy answers. But I am not convinced that you have tried hard enough to solve them.

Even though the speech is 50 years old, that passage could easily be lifted from a speech given yesterday, as not only is the list of pressures to which broadcasters succumb unchanged, but also television is still bad.

Minow also addressed the unique nature of terrestrial broadcast in the U.S. — the specific frequencies on which content is broadcast are licensed to broadcasters by the government. Broadcasters have not owned these frequencies; we have been giving them permission. Minow said:

[The] people own the air. And they own it as much in prime evening time as they do at six o’clock Sunday morning. For every hour that the people give you — you owe them something. And I intend to see that your debt is paid with service.

TV history is littered with embarrassments. Our parents and grand-parents lived through the casual racism of “Amos ’n’ Andy,” the ingrained sexism of every ’50s show from “The Honeymooners” on up, the socioeconomic patronizing of “The Beverly Hillbillies” and “Petticoat Junction,” and the slur on affable clumsy people that was “Gilligan’s Island” — all of these were icky. “Repo Games” breaks out of that pack, however, bare weeks after its premiere. It is offensive. It does not mean well, and no matter how many cars are saved because someone knows the capitol of Iowa, it does no good. The people’s airwaves should expect better.