The End of the Rodeo for the World's Greatest Cowboy

by Mike Riggs

The World’s Greatest Cowboy had to be peeled off his barstool and carried home the night he killed a man.

The next morning, in the presence of two deputies from the DeSoto County Sheriff’s Department, the cowboy sat, elbows on his knees, face protected from the light of day by a latticework of fingers, and tried to remember shooting Edward Delaney. He sucked in air, and smelled burnt powder. He breathed out, and caught a whiff of high-proof mucus. He remembered nothing.

Here’s what the deputies already knew: The night before, one of Delaney’s bartenders called him from the Corral Bar, which he owned, and told him that the soused cowboy needed a ride home. More than a few people in town had heard the rumor that Delaney was involved with the cowboy’s wife, a redheaded cabaret dancer named Linda. The deputies filled in the blanks. After exiting Delaney’s truck, the cowboy stumbled inside his house, fetched his 30–30 rifle, returned to the front door and sent 11 grams of lead spiraling through Delaney’s rear window as he pulled towards the road. Whatever the cowboy was aiming for — a taillight, a mirror — it was Delaney’s brain that had a bullet hole in it.

A few weeks later, the cowboy traded in his old life — world tours, shiny buckles, adoring fans, money, his second wife, his only son — in exchange for a second-degree murder conviction and a 15-year prison sentence. It was 1971.

Forty years later, the World’s Greatest Cowboy is finally learning to be great at other things.

***

Charlie Driver lives in an old singlewide trailer just off I-10 in the Florida Panhandle. His place is not on any map, so when he entertains visitors from out of town, he tells them to either turn left at the Arby’s if they are coming from the interstate, or right if they are coming from Monticello (pronounced Monti-SELL-o). The first time I called him, asking to interview the rodeo legend my grandmother told me about when I was a little boy, and for directions, Driver told me not to come at all.

I ended up driving around Jefferson County, Fla., for six hours on the hottest day of June 2009. Traffic in Monticello was bumper-to-bumper. The annual Watermelon Festival was happening, and a car crash near the parade route had killed an old lady and injured a few others. The lead story in the Tallahassee Democrat’s weekend edition was headlined “‘Miserably Hot’ Weekend.” The quote belonged to a jogger who the paper had interviewed on Friday.

After several hours of sweating and driving, I called Driver again, and this time I told him I’d flown from D.C. to Orlando, then driven from Orlando to the Panhandle, just to meet him. Driver laughed and laughed. Then he invited me to an “old cowboy-lookin’ place” on the outskirts of town, and told me to turn right at the Arby’s.

Everything Charlie Driver has ever done in his entire life is collected behind the Arby’s. There is the trailer, and looming behind and above it, a rodeo arena. Rust has eaten the red paint off the rails, and the bleachers are bowed and warped, but its very existence is nevertheless grand and shocking: A rodeo arena. Behind a single-wide trailer. Behind an Arby’s.

Driver used to throw a rodeo every year during the Watermelon Festival. His grandstands can seat roughly 900 people. “A thousand, if a sponsor asks,” Driver says “We can have kids sit on top of the buildings.”

Sponsors no longer ask, and Driver could not throw a rodeo now if his life depended on it.

For the last two years Driver has been recovering from a spate of illnesses, the most traumatic of which was Guillain-Barré syndrome, a freak autoimmune disorder that causes paralysis and, in some cases, death. One morning, he says, he woke up and couldn’t move his toes or his legs. Then the syndrome worked its way up to his chest, where it nearly stopped him from breathing. For one whole day, he couldn’t move his arms or hands. That was when he decided to visit a doctor.

The disease pushed Driver past a threshold: He now feels as old as he looks.

The skin on his hands, arms, and face is paper-thin. The bruises puddled underneath the dermis are as detailed as forensic slides. While he is not fat, he does have a belly and jowls. He is shorter, but no less stylish, wearing a gleaming, saucer-sized brass buckle below his slight, flannel-swathed paunch, a creamy white-straw Stetson cowboy hat atop a head of brownish red hair, and navy Wranglers that cling to his spindly legs. He walks with his arms and hands out to his side, a black cane in one, the other balled up tight.

We retreat from the June weather into Driver’s “cowboy shack,” an air-conditioned storage shed on cinderblocks. This is where Driver keeps most of his rodeo memories. Every inch of wall is covered with photographs, and countless more reside in knee-high stacks on the floor.

Charlie Driver’s right hand shakes as he fishes a cigarillo from his breast pocket. “Give me a light,” he says. “And don’t tell Bambi about this.”

Driver’s doctors don’t want him smoking. Nor does Bambi, his wife. But a condition of my visit is that he can kick back and sneak a few much-wanted hits off his secret cigarillo stash while I ask him about his life. His eyes travel through photos as he talks.

Massive bulls with their hind legs high up in the air, Driver pitching forward, his right hand high above his head; a grinning Driver accepting a cardboard check; a group of well-dressed gauchos standing beside Driver, the Madison Square Garden sign behind them.

There is a secret history not shown on the walls of Driver’s cowboy shack. Delaney’s death and the collapse of Driver’s rodeo career are parts of it, but not all of it. I ask about the pictures that are not on the walls. The family that has been erased from the photo album.

Driver’s rolls the stubbed out cigarillo between his fingers, brushes ash off his chest. “Sometimes,” he says, “things just fall apart, and we are never the same.”

***

Before Florida had Disney World, NASCAR, or Lynyrd Skynyrd, it had what Garth Brooks once referred to as the “goddamn rodeo.” Rodeo started in Spanish Mexico before coming to the United States, and so it was only natural sense that the settlers who chased feral Spanish cattle through Florida’s swamps would adopt the sport as their own.

Like church and court hearings, rodeo has a certain theatrical archness about it that Floridians love. There are hard and fast rules — eight seconds on an animal to score, a rider’s free hand can’t touch hide; a tried-and-true order of events that never changes — National anthem, bareback horse riding, steer wrestling, team roping, saddle bronc riding, barrel racing, and bull riding; and clowns.

Also like church, (and very much unlike NASCAR races, Disney and Skynyrd shows), the rodeo gave rural Floridians a reason to put on their Sunday best. They do not now, nor have they ever, showed up to a rodeo in jorts. Rodeo-goers wear their nicest denim, their nicest boots, their nicest button-front long sleeve shirts, and their nicest Stetson cowboy hats, which they keep boxed the rest of the year.

Dating back to the early 20th century, at a rodeo was the only place ranch hands and ranchers and citrus pickers and grove owners sat side by side. And like with most sports, Florida had its own homegrown legends. In the 1960s, glory days for Florida rodeo, there was Joe Johns, the 5-foot-5 Seminole from Okeechobee who rode bucking horses like he’d been glued to their hides; Pete Clemons, the wiry bull-rider-turned-cattle magnate who won more championship titles in a year than most riders managed to collect in a career; and Matt Condo, the orphaned young gun who made it all the way to the national semifinals before a poorly cinched rope broke his riding hand.

And then there was Charlie Driver.

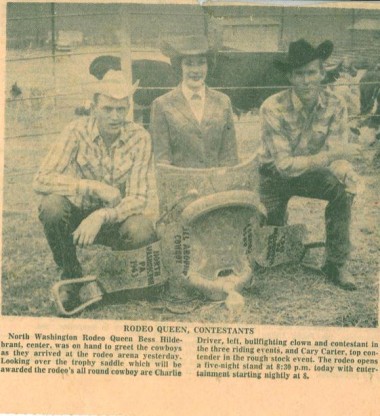

“I remember exactly what direction I was facing when I first saw Charlie,” says Nancy Barber, a former ballroom dance instructor and school administrator in Osceola County, where the schools let out on a Friday in February in celebration of the Silver Spurs Rodeo, instead of the following Monday, which is President’s Day.

“I was 11 years old, and I was facing east, and Charlie Driver walked out of my house behind my father,” says Barber. “And I know my jaw must have been hanging open, because he was undoubtedly the most gorgeous human being I’d ever seen in my entire life.” Her voice softens. “He was tall and slender and a cowboy, and I remember him having a wonderful smile.”

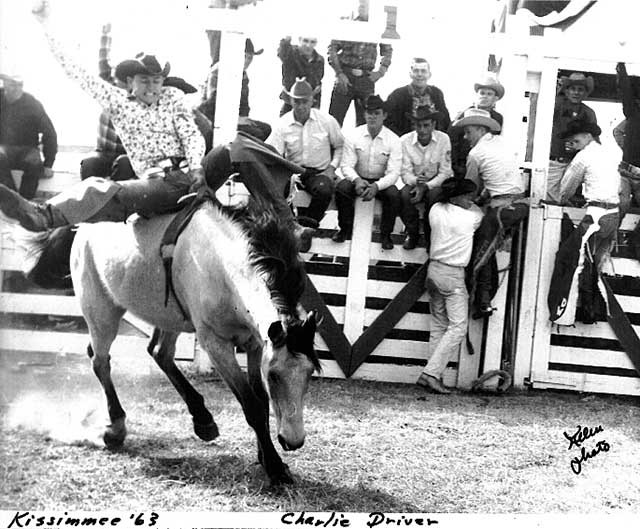

It was spring 1963, and Driver had drifted down to Kissimmee, in Osceola County, to make his name. Barber’s father, a rancher who everyone called Little Bill, took Driver on as a hand while he cut his teeth at the Silver Spurs.

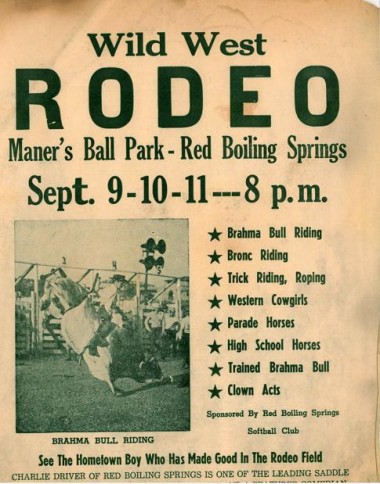

Though he seemingly appeared out of nowhere, Driver had been working toward an opportunity like this since he was a 14-year-old in Red Boiling Springs, Tennessee. That was how old Driver was when he realized he hated life on the farm. His mother and father farmed corn and tobacco, and they lived simply, raising everything they ate, from vegetables to hogs. They made enough from their crops to get by, but Driver did not want to just get by. He wanted to be a star.

A neighbor’s ornery colt gave him an out. Driver had been tasked with breaking the animal, but several hours in, he couldn’t get the animal to so much lead, much less ride. All he could do was hold as the horse careened around its pen. This skill impressed the neighbor, who decided to take Driver and the colt to Moss, Tennessee, and sell the horse as a bucking bronco. Driver had a better idea. He borrowed $5 from his uncle, and once he got to Moss, entered himself as a contestant.

“I was the only guy that rode a bull for eight seconds that night,” Driver says. He spent most of his prize money in a pool hall, buying chips and sodas for cute girls.

His parents had no idea. “They worked hard for every quarter they got. I never did tell them that I made a whole $50 in one night — that was a pile of money. That set me afire on being a rough-stock rider. That’s all I wanted to do from then on.”

When Driver finished high school, he left Red Boiling Springs with nothing but a knapsack and some pocket money from his grandfather, and hit the road. He hitch-hiked to Georgia, where he ran out of money and found the Cherokee Wild West Show. In Cherokee’s employ, Driver discovered that his showing in Springfield wasn’t a fluke. Cherokee’s animals were wild and mangy, and Driver rode and clowned them like show ponies. For all his talents, there was still an element of amateurism to Cherokee’s outfit. The real test was in Florida.

“He came [to Kissimmee], and I mean he was tall, and agile, and he could fight bulls,” says Tom Bass, who rode with Driver throughout the ’60s and now announces at the Silver Spurs Rodeo in Kissimmee, the state’s oldest.

Bass is the closest thing Central Florida has to an official rodeo historian. His family has lived in Osceola County since the late 1800s. His mother, Georgette Bass, was one of the last women to compete against men in rough stock events like bronc riding and bareback riding, and stopped only after she broke her neck during a competition.

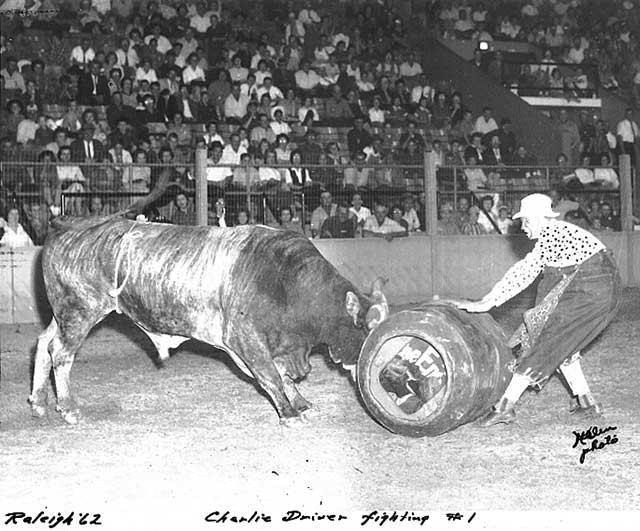

What made Driver exceptional, argues Bass, is that he was good at everything. “Charlie could stay busy the whole rodeo,” he says. “He could ride the broncs, ride the bulls, fight the bulls.”

It’s the bull-fighter’s job to distract an enraged and horny half-ton beast while the thrown rider books it for the fences. Most of them don’t last long, and the ones that can’t seem to quit eventually graduate to playing the “barrel man,” so-named for his job of running and hiding in a padded barrel when the bulls get ornery.

“Being dumb and quick won’t make you a good bullfighter. There’s more to it than that. You gotta be smart and quick and have some cow in ya,” says Grant Harris, owner of the Cowtown Rodeo in New Jersey, who traveled the rodeo circuit with Driver when he was a child.

“That’s what Charlie had. Lots of cow. He knew how to get around them and could figure them out.”

In the 1960s, the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association had yet to mandate a minimum of two bullfighters and a barrel man in the ring during bull-riding events. It was often just Driver and a barrel man, and it may as well have been just Driver. He somehow managed to make himself the center of attention even when he wasn’t the main event. During one show, Driver was paired with an easily winded barrel man who would hop in his water barrel and pretend to be knocked out as the bull rampaged after Driver. While concussions are a reality for rodeo clowns, Driver suspected that his bull-fighting partner was taking advantage. So the next time his partner pretended to pass out, Driver grabbed a crumpled rodeo program from his pocket, ran past the bull and up to the barrel, lit the program on fire and dropped it on top of his snoozing partner. Even the barrel man found it funny, because there was nothing Driver would to someone that he wouldn’t do to himself.

“In Kissimmee, they used to have these big old black and white bulls, and they called all of them ‘Speck.’” Bass says. “Some joker took a piece of clothes hanger and wired a $50 bill between Speck’s horns and told Charlie to fetch it.”

Bass stops mid anecdote to laugh.

“Charlie played around with him, got him up next to the fence, then jumped up on the rails, reached down, and got the fifty off him. Then he says, ‘You’ll have to come up with something better than that.’”

“He never ran out of air,” says Bass.

***

The black-and-white spotted bull calf behind Charlie Driver’s trailer tosses its head and paws up plumes of sugar sand when I place my elbows on the rusted bars of its pen. He’s too small to do much damage. His horns are just two-inch stubs, and his legs are still stick-like. I am staying alert, however, because this bull calf has the eyes of the devil.

Nearby, Bambi watches. She’s wearing brown boots stained with cow shit and dirt, a wiry bun of grey-tinged black hair pinned up off her neck. The bull calf snorts again and Bambi calls out to me from the warped aluminum bleachers a few feet away, “It’s because you’re here. He doesn’t like strangers.”

Driver seems to be enjoying the interruption. A shaky finger flies to various points of anatomy in order to illustrate that the Mexican stock gives the animal smaller ears and a shorter skull, while the Brahma gives it muscle mass. Nowadays, talking cows is easier for him than talking about — or doing — anything else.

Driver grabs onto the top rung of the pen with one hand and leans into the rails to take some of the stress off of his right wrist. Then he clucks his tongue, and the bull-calf drops its head and charges the gate. I trip backward, but Driver only chuckles and nods, a proud grin tearing across his face.

“The bull’s just getting used to hating people,” he says.

A couple of cowhands will come here next weekend and give the calf another go-round with a motorized bucking strap. Then they’ll try him out with human riders. If the hate runs deep enough, the riders will turn the calf into the kind of wild sonofabitch that Driver can then ship from rodeo to rodeo.

“Mosquitoes will be out soon,” I say. Bambi and Charlie nod. The bull calf has grown bored and wandered back to its mother. Halfway back to my car, Driver stops as if he has forgotten something.

“Mike, what did you come out here for?” he asks.

For a moment, the Lord strikes me dumb. On the drive to Monticello, I had rehearsed my questions about Delaney’s murder. After two hours in Driver’s company, I have not asked one of them. I am not scared, or even embarrassed, but suddenly aware that there is more to his existence than the terrible, earth-shattering act of violence he committed 40 years ago in a drunken haze.

So what I say is this: “I came here to write a story about the greatest rodeo man who ever lived.”

Driver laughs until he cannot breathe.

***

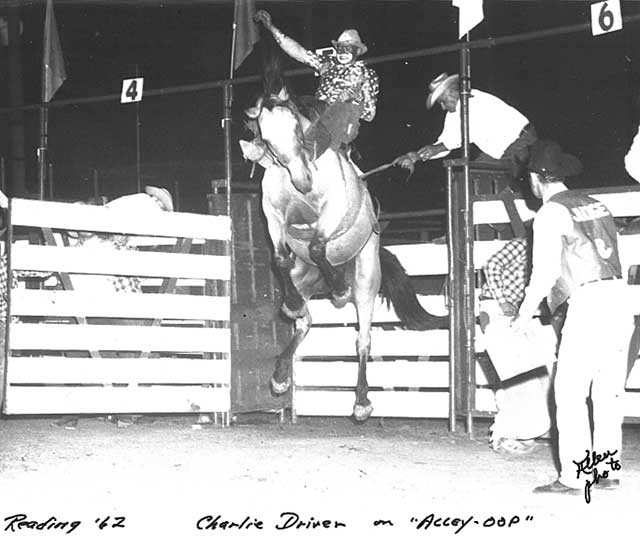

By 1966, Driver’s hard work had started to pay off. He was nationally ranked in the top 30 out of 5,000 registered rodeo riders. He’d won the all-around competitions at the Silver Spurs, Arcadia and Okeechobee — the three biggest and longest running rodeos in Florida — as well as countless rodeos big and small across the country. He’d even shared space on a scoreboard with Jim Shoulders, “the Babe Ruth of rodeo,” during a bull-riding event in Dallas: The event featured 88 bull-riders from across North America; Shoulders placed first, Driver placed seventh.

“If he drew good, he was going to get a check,” Grant Harris says, referring to a practice in which riders draw slips out of a hat to determine who will ride which animal. (The best stock, which travel from rodeo to rodeo, have almost always been more famous than their riders. A good draw can speak to a rider’s prowess.)

Driver, 25, was also still clowning at every rodeo.

“He was that kind of a talent,” says Harris.

With the riding came partying. The term “buckle bunny” originated during Driver’s heyday to describe what are essentially rodeo groupies. These women proved a perpetual distraction for Driver. Anything with a skirt and a smile entranced him. The women wanted him back. He was lean and young and handsome and funny.

I suspect one reason my grandmother told me about Driver when I was little is because, in 1968, he made a play for her affections despite her being married to an Episcopal priest. They were at a mutual friend’s house when Driver slipped away to his truck and fetched a bottle of whiskey. When he returned, he sat down next to my grandmother, spun the lid and said, “I didn’t know what I was keeping it for, but now I do.” My grandmother rebuffed his advances. “I was not tempted, but I was curious,” she tells me 40 years later. While Driver doesn’t remember the incident, he concedes that at the time, “If they’d drink it, I’d pour it in ‘em.”

Booze was as integral to the cowboy experience as learning to use a lasso, and as detrimental to a cowboy’s life as taunting a bull when you have nowhere to run.

For Driver, the never-ending party was a sign that he’d made it. “He was always laughing, always had jokes to tell, fun to be around,” Harris says. “And drinking was kind of a big part of things in those days.”

Driver was also well into his second marriage to a Florida woman named Linda, and now had a young son named Rusty, who had his mother’s red hair and his father’s playful disposition. (His first marriage, to a barrel racer he’d met while working for Cherokee, wasn’t the domestic kind.)

In Linda, Driver had found a woman who could balance good times with family living. “Linda was dancing on the girl’s show at the carnival at the state fair,” Driver tells me. “Me and Ole Matt [Condo, who Drive took under his wing] was going down through there one night after the rodeo, and I told Matt I sure would like to meet Ole Red. And Matt said, ‘Ole Red isn’t going to talk to you, she can get anybody she wants.’ I said, ‘Oh hell yeah, Ole Red will talk to me.’ I walked right up to the stage and gave her the ‘come here’ sign, and she leaned down and I said, ‘Hey, let’s eat breakfast when this show’s over.’ And things went on from there.”

Linda was a fellow wild child, the daughter of a wealthy Tampa businessman who managed some of the city’s best restaurants. With Linda’s help, Driver traveled to Puerto Rico, where he hosted a rodeo that ran for three weeks. After Rusty was born, however, Linda wanted a normal life. Driver, however, had begun to take partying more seriously than riding.

Early one evening in ’69, Driver, stinking of booze and toting an expensive prize-saddle, jumped on the platform at a cattle auction. Brandishing the saddle, he demanded that the auctioneer stop what he was doing and sell the saddle then and there. When the auctioneer balked, Driver explained that he had bought drinks for everyone at the bar down the road and needed to pay his tab; he wasn’t leaving until someone bought that saddle for $900. In deference to Driver’s reputation, the auctioneer sold the saddle for far less than $900, but more than enough to pay the tab, and Driver returned to the bar in time for one more round.

Around the same time, Driver and a bull rider from New York named Dominic Moretti were invited to a party at a wealthy ranching couple’s house in Kissimmee. “Now Dominic, these people are good people,” Driver remembers telling his New York rodeo partner. “Don’t get over there and pee in the pool or do something stupid.”

The party started off well enough. People were eating and drinking and dancing. Moretti was not peeing in the pool; Driver was getting lit. A few hours in, some local jocks showed up, and with them, a bevy of high school girls, one of whom had just been crowned Ms. Tangerine.

“Well, I danced with little Ms. Tangerine a time or two, and then I told her, ‘Let’s get out of here and grab a hamburger or something,” Driver says. When the two returned, Ms. Tangerine’s boyfriend was waiting to deliver a beating.

“I heard someone say, ‘Kick that cowboy’s ass’ when we got back to the house,” Driver says. As the group circled around the cowboy, a soused Moretti appeared in the yard gripping a handgun, and threatened to shoot into the crowd. “I told Dominic, ‘It’s a fight, not a killing,’” Driver says. “And ole Dominic whispers, ‘It’s just a toy.’”

Driver grins, his teeth as big and white as piano keys.

“So I hollered for him to shoot the sonsabitches. I’ve never seen anyone run so fast.”

***

The day in 1971 that two court-appointed psychiatrists determined Driver was fit to stand trial for Delaney’s murder may have been the first time in years that the World’s Greatest Rodeo Clown woke up sober. The prospect of 15 years in a Florida prison, handed down a few months later, was even more sobering.

Yet, thanks to a man named Doyle Conner, Driver’s prison stay, 1975 to 1977, was short and easy. Elected to the state legislature in 1950 at the age of 21, speaker of the Florida House of Representatives by 28, and agricultural commissioner by 31, Conner wielded immense power as a member of the governor’s cabinet. Fail-safes, written into Florida’s constitution during Reconstruction, gave cabinet members, as well as the attorney general, voting power over commutations and pardons.

“Someone in Arcadia who knew Charlie and knew Doyle, knew that the only way Charlie could get through his sentence is if they didn’t put him in a jail cell and leave him there the whole time.”

No one at the Florida State Penitentiary batted an eye when Conner obtained a pardon for Driver after only two years of a 15-year sentence and put him to work on his ranch in Tallahassee. Or, a few years later, when the Florida Department of Agriculture hired Driver to conduct research on cattle breeding.

Very few people see Driver as having not paid his debt. “But for the grace of God, it would have been one of us that did same thing,” Bass says when I ask him about the night in January of 1972 that forever changed Driver’s life. The incident is seldom talked about. My uncle, a cowboy and former bronc rider who now raises stock part-time, sees no lack of justice. “What happened just happened,” he says after a short silence. “There’s no need to judge. It was late at night and the whiskey was talking… Charlie rode a lot of hard miles and he’s got his wounds,” he says. “But he understands rodeo and he understands stock. He’s a genuinely decent kind of fella.”

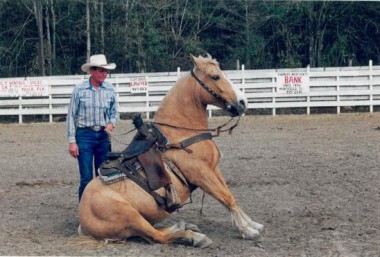

Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, Driver rodeo-ed on weekends while working for the state, perfecting a stunt act with a horse named 40 and a Longhorn steer named Raw Hide. He raised stock, hosted the rodeo during the Watermelon festival and visited with his buddies from Kissimmee and Arcadia. He stayed married to his third wife, Bambi, a feat considering his record. He drank too much.

It’s possible he thought the worst was behind him, but the worst, and even the best, were very much ahead of him.

***

“I haven’t laughed in goddamn months,” Driver says into the phone. He tilts his head back to the ceiling, closes his eyes and wheezes.

He is talking on the phone to a friend who has called to check on him. He’s trying to convince the friend that he is not utterly falling apart.

He is lying.

Driver met Bambi almost 30 years ago when he was working at the Florida Department of Agriculture. “She was my bossman’s sister. And he introduced us and we got to going to some of them rodeos and dating, and it just kinda took,” Driver says.

A black-haired, dark-eyed woman with a narrow face and slender tobacco-tan arms, Bambi stood by Driver through his second and less noteworthy rodeo career; through bad drunks and failed business ventures. They married 14 years after they first met, and with Bambi’s help, Driver sobered up for good in 2000. During the 16 months Driver spent in and out of hospitals recovering from both Guillain-Barre syndrome and a respiratory infection, Bambi took over his cattle operation, making sure stock were shipped to various rodeos as well as buying, loading and unloading 50-pound sacks of feed. When she wasn’t managing the ranch, she was at Driver’s side, feeding him, bathing him and moving his arms and legs — which Driver had lost the ability to move on his own — to keep them from atrophying.

In the fall of 2009, several months after I first visited Driver, Bambi was carrying a bucket of feed out to the pens when she collapsed. A few days later, doctors discovered malignant tumors in her stomach and intestines. Five months, several surgeries, and a chemo treatment later, cancer is still eating away at the only person in Driver’s life.

Today, Bambi is a few hours south of Monticello, making the arrangements for her mother’s funeral.

“They called me when she was asleep and I didn’t even tell her,” Driver says into the phone. “I waited ’til this morning, and of course, she cried.”

Driver pauses. “It’s coming strong, but I can handle it. I can handle it.”

There are only two places where one can sit down in Driver’s living room: A recliner, in which Driver is currently kicked back, watching the Superior Productions cattle auction on a small flat-screen TV, and a wheelchair covered in blankets that both Driver and Bambi have taken turns sitting in over the last two years. The only other piece of furniture, an ancient and ragged loveseat, is covered in unfolded laundry and Planter’s peanut jars full of loose change. “I call this my office,” Driver says, surveying the room. “I got numbers wrote all over everywhere, but I can’t find a damn thing. Bambi’s been sick for so long, and I was sick all last year, we just got to where we chuck, pitch and throw things down.”

I squeeze my way onto the loveseat, and Driver nods to an ashtray embedded between two cushions. I fish it out while Driver lights a cigarillo. When he tosses the lighter my way, I ask if he’s sure I can smoke in the trailer. “Ain’t no point worrying about it now, bo’,” he says. For a while after that, the only noises in the room are the auctioneer on television and the sound of two men slowly, deliberately, exhaling.

Eventually, Driver begins to crack wise about death. “I want to be cremated,” he says.

“They put you in a box, and you can’t go nowhere. I’ve been locked up before, and it ain’t worth a shit,” Driver says, laughing.

“Yessir, I wanna be cremated and dropped off the Branford Bridge over the Suwannee with all those pretty girls skinny-dipping.”

Two years before, doctors operated on an aneurysm on Driver’s heart. Days after his release from heart surgery, he was re-admitted to the hospital in extreme pain. His intestines were twisted. He died on the table during the emergency procedure to fix his bowels and was revived. Shortly after leaving the hospital, he began suffering from Guillaine-Barré syndrome. Other problems have reared their heads since then: high blood pressure, more chest pains.

Forty years after he took a man’s life, Driver is now facing the end of his own. But what gets him, is that he’s facing the end of his life with Bambi.

Driver does not curse his bad luck. For the first time in his 70 years on this planet, he has no doubt that he deserves to be alive. “God was looking out for me all this time, but I never knew why,” he says through a cloud of smoke. “The only thing I can think of is that he wanted me to look after Bambi.”

He nods after he says this, more to himself than me. “If the diseases get us, me and ole Bambi had a good ride.”

We watch the cattle auction for a while longer, and the hosts pontificate that good genetics don’t always make for a winner. “That’s right,” Driver says to the TV, “you can’t tell just by their momma and daddy if they’re gonna fly.” Around dinnertime, I tell Driver I’m going to get out of his hair. He chuckles and tells me that I have demonstrated unnaturally bad timing in all of our interactions.

I ask if he’d like me to run to the store for him and grab some groceries. Driver shakes his head. “I’m just killing time, bo’. Just waiting by the phone to see if my old woman makes it all right.”

Outside, the air is heavy with the scents of manure and blazing sugar sand. A cicada cacophony rises and falls in time with the waves of a liberating breeze. In the pasture next to the trailer, an adolescent bull covered in black and white spots languidly looks my way, flicks his tail, and goes back to grazing. Six months from now, the calf and all the other stock will be gone. Driver will tell me that he is too worn out to take care of them and Bambi both, and that he has chosen Bambi.

Mike Riggs was born and raised in Central Florida. He now lives and works in Washington, D.C.