Thaw

by Jeffrey MacIntyre

Most days upstate, we’re tearing pages from the Iron and Wine songbook. Big box stores it is not. Yet here we are in midwinter at a first light trip, a county away from our Hudson Valley home, to a twenty-four-hour Walmart, the approximate armpit of the American dream. I’m loading remnant boxes as we start packing house. Where we’re headed, there are chickens in front yards.

We’re moving again, inland, a mile up the main street of Cold Spring, down a dirt road to a stone home in a thicket of woods. No bollards and no paving stones here. Straight to a forest dark’s dark, lit only by what breaks through the winter canopy overhead. The street name itself, a doggerel of the married couple who first cut the dirt road, is rednecked beyond recognition and flocked with wildlife. In city person shorthand, it’s a sight for sore eyes.

At the exit door to our first long winter, this hamlet’s charms can still surprise us.

We returned a mountain of overdue books to be told there are no late fees.

We read an ad in the local paper, a local thanking his neighbors for the gift of his new snow blower.

We infiltrated the high mass of an Army/Navy contest, toasted by a riot of fans.

We watched the milling deer, lazily eyeing us between head-dips into the forest floor nettles. The only noise all around was their munching.

Carpetbagging makes for good human company, too.

Even as my head, pasted to a train car window most mornings, scans downriver, my fondest day-end thoughts reliably point back home. All our happiest little moments are fastened in deep-wooded tranquility. We’re held fast and drowsy in place, at our fullest ease in its seasonal grip.

In the lower reaches of the Hudson Valley, winter is a wilderness period for locals, a season where the everyday is snowbound, ice-blasted and wind-tossed beyond what my delicate Pacific Northwest roots can easily handle. But it’s good work, getting your mettle up to match the rougher elements. I have spent more than my fair share of nights this winter, peering at the moonlit Hoth outside my deck window, the river encased as single frozen floe, the turrets of West Point glinting in the near dark of the far shore. That still small voice inside, puffed up with frost, has something to say. Forget the highs and low of petits bourgeois struggle hereabouts, it’s the restful trappings of nothing doing for miles around that make living here its own delight. The closest reminders those nights of anything beyond is the mild riverside hum, the rumble of freight trains rolling along the Hudson’s western shore.

Meanwhile, my own train commutes kept pace with the march out of the winter season. Time ticks by on a flinty upstate atomic clock, and the barbed wire of Sing Sing alongside the train car pales to the gleaming Fukushima fantasia of Indian Point.

Nothing heightens the appeals of home than taking frequent leave of it. My near-daily toddles to Turtle Bay, and a full week’s twirl among the Midtown drudges, is a slow-moving marvel of a commute, and it’s helped make our move upriver all the more enjoyable by contrast. The thread of train commute time is itself a great inviting gob of reading and relaxation.

Outside, the long fugue months of winter have hit the narrows of the Hudson River full in the mouth. But it’s a big pretty commute southward by train. The window side view: fat floes below, full-bleed white above, and a Rorschach smudge where the opposite shore of the Hudson should be. All late winter it’s been a dense snow globe glimpsed from an upstate train. The elements blasted the fjord with ice sheets — lozenges of snow and ice — and painted the length of West Point on the far bank, and Phillipstown on the near. From the train car it’s a bright canvas stretched taut. The air is thick with lazy gales, even on a bolt from the blue bright sky morning upstate. Travelers on the platform wince; the brunt of wind chill are invisible flecks of ice flitting past exposed ears. The air blowing off the Hudson is like a handshake with concertina wire. Even once the snow and ice receded, its grip has left the soil, and us, ruddy and gray.

The entire point of leaving New York — the snide side truth of carpetbaggers everywhere — was to better enjoy it, to steal some distance and perspective about the city things worth returning for. Nearly one year in, the draw of a train trip’s simple remove has only grown.

At my stop the morning train cars are nearly empty, sparsely seated by Poughkeepsie and Beacon travelers. Folks file in rapidly as we progress south along the river, corduroy waves lapping peacefully railside.

The inside of the AM train car, more often than not, is lit with computer and tablet screens, a creepy banquet of spreadsheets and PowerPointsmanship. If I’m lucky, I can eavesdrop on the small talk of the poker club, a gang-of-four regulars who pluck an ad board down, using it as their personal small stakes table.

Most returns home, my fellow passengers home are stone cold cut-outs of the gray flannel man, ambered in their gin, a half-century on and loping leadenly into their alcoholic autumns. There are fewer number crunchers and more readers. Some blessed days, it feels like a riverside NYPL reading room.

It’s hard to resist revisiting the funny gamble that got us here. For us, it’s clearer now, at the approaching hingepoint of a year’s time up here, that going upriver was more Huck Finn than Mr. Kurtz, a lighting out for territories that makes inevitable returns more pleasing by contrast. City versus country living: if you can swing it, why choose?

Jeffrey MacIntyre is a freelance writer and consultant. His writing appears widely.

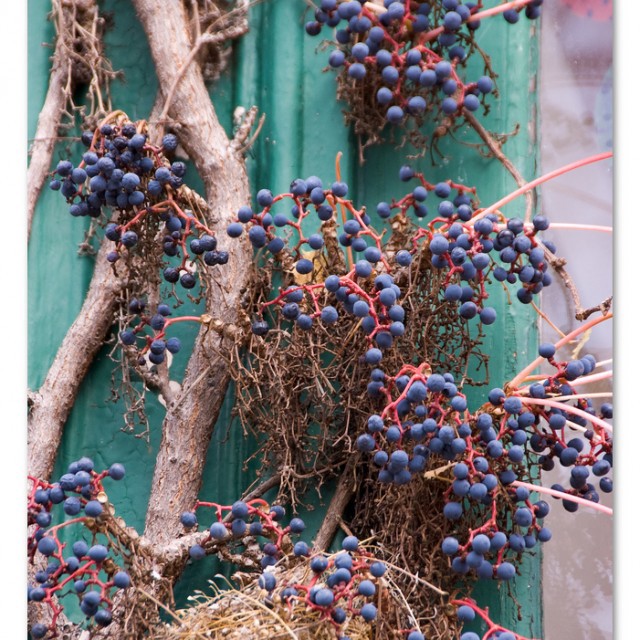

Photo credits in order of appearance: “Hudson River — Cold Spring , N.Y.” by Ricardo Noltenius; “_MG_2811” by MK Marino; “cold spring” by MK Marino; “_MG_2708” by MK Marino; “Winter wasteland” by Father Matthew Green; “Free Snow” by MK Marino; “Cold spring riverfront” by Daryl; and “Cold Spring” by Robin “Evil Bob” A.

All images via Flickr and used with permission.