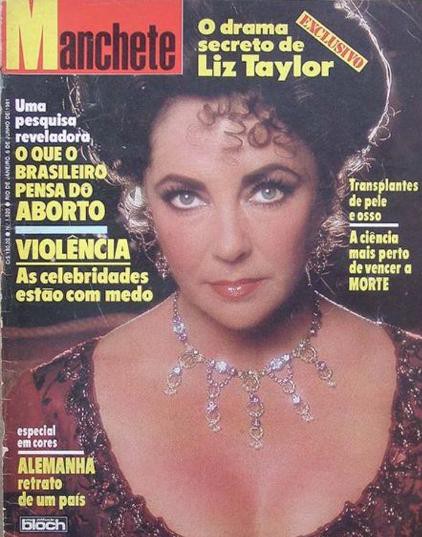

Elizabeth Taylor and AIDS: A Brief History of the 80s

by Phoebe Connelly

Elizabeth Taylor turned 49 in 1981, and she had behind her six marriages and 55 feature films. In November of that year, she would appear on daytime soap “General Hospital” as a mysterious widow. She was also in the final year of her marriage to Republican Congressman John Warner of Virginia. “The Republican women told me, ‘You simply cannot wear the purple pantsuit you’ve been campaigning in anymore,’” she told Michael Kors, later, in Harpers Bazaar. “I ended up in a tweed suit. Me. Little tweed suits. What I won’t do for love.”

By 1985, after a divorce and a stint in rehab, the actress had fashioned herself into the most vocal mainstream champion for AIDS awareness and prevention. She was the founding chair of the first mainstream (read: straight) AIDS foundation, convinced then-president Ronald Reagan to speak at the foundation’s 1987 gala dinner (his second public speech on the disease): in it, he opened with some jokes and then quoted Auden. She regularly raised millions of dollars for AIDS education and treatment until her death. “She redefined the role of the celebrity by daring to talk about AIDS way back in the ’80s, when no one else wanted to touch it,” wrote Michael Musto yesterday at the Village Voice. “If you have fame,” Taylor told Dominick Dunne at a 1985 AIDS charity gala, “this is the way to use it.”

The precipitating event for Taylor’s activism was 1950s movie heartthrob Rock Hudson’s announcement from Paris, in July of 1985, that he had AIDS. Taylor starred opposite Hudson in the 1956 Texas ranch melodrama Giant. Hudson’s announcement made waves, as did his death three months later.

Taylor’s involvement also marked the beginning of the disease becoming an acceptable straight charity cause. This was greeted with mixed feelings by the gay community, which had spent more than half a decade trying to gain recognition for a disease that was sickening and killing thousands. Taylor was recruited by Dr. Mathilde Krim, a professor of public health at Columbia University, to co-found the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). Like many of Krim’s fundraising connections, this one likely came through Krim’s husband, who was president of Orion Pictures.

In September of that year, Taylor and amfAR held a Hollywood bash for AIDS research. The benefit had to move locations after Hudson went public with his diagnosis, because stars suddenly lined up to purchase tickets at $500 a head. “Everyone of any consequence in the film industry went to that party,” Dunne wrote in Vanity Fair. “Friends started calling me,” Taylor told Newsweek in 2001, “’Don’t go near this one, Elizabeth. It’s not a sympathetic charity.’ Then a couple of months before the dinner it came out that Rock [Hudson] had AIDS. All of a sudden the city did a total spin. It was like, ‘Oh, one of us got it, it’s not just bums in the gutter.’” Among the 2,500 attendees were Betty Ford, Rod Stewart, Carol Burnett, Shirley MacLaine and Burt Lancaster; Rod Stewart and Cyndi Lauper performed. According to the Times, “The Los Angeles homosexual community has also strongly backed the benefit.” Three Andy Warhol paintings were auctioned off.

“How we behave at this moment we’re going to remember for the rest of lives, long after this disease has passed,” MacLaine said at the event. Taylor continued to fundraise for the organization, at one point, editing a telegram sent to 94 potential patrons asking them to contribute to a cabaret benefit. Joan Kroc, heir to the McDonald’s fortune, responded, and arrived at the event to present Taylor with a $1 million check.

Making AIDS mainstream, even as it continued to predominately affect the gay community, gave fundraisers access to money, even as it marginalized the voices of those closest to the suffering. Susan Maizel Chambre, in her history of AIDS and New York, notes an interview Krim gave to Newsweek in 1987 about the role she and Taylor were able to play. “We had to have credibility; we had to be seen as a mainstream group and not a gay organization.”

* * *

What was most unusual about Taylor was how her fundraising was ongoing. In 1991, she donated the proceeds from the sale of photographs of her 8th wedding (to construction worker Larry Fortensky) to her newly created Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation. At this point, the actress had significantly scaled back her work with amfAR due to illness and personal clashes with the staff. For her 65th birthday in 1997, the violet-eyed star threw a televised birthday bash complete with a new song performed by Michael Jackson. The event raised over $1 million for AIDS research. Taylor checked in to the hospital that same week for high-risk surgery to remove a brain tumor.

It’s easy, 30 years in now, to take Taylor as yet another pretty face getting her bonifides via charity work. It’s difficult to express the stigma that accompanied AIDS in the 1980s. The Canadian magazine Maclean’s ran a rather nasty column addressed to Taylor, deriding the actress for championing “the trendiest of all diseases. Trendy people die of it and trendy people go onstage and emote about it.” Adweek reported that Taylor was rumored to have lost her advertising contract with Coca Cola because of her AIDS work.

In 1992, a reporter implied that Taylor cared more about AIDS fundraising than her mother, who had been ill. “Are you saying I don’t care about my mother?” she asked. “That’s a really shitty thing to say.”

And if you were a straight, high-profile beauty willing to talk publicly about a disease that even today predominately affects minority populations, then the assumption is that you must suffer from AIDS yourself. When the actress was hospitalized for pneumonia in 1990, she was plagued with rumors that it was AIDS.

None of this is to say that Taylor was a saint. She is, after all, the woman who wrote a book titled My Love Affair With Jewelry. But she used her very public persona to transform mainstream American and political opinion on AIDS. The woman who polished her sapphire on the hem of her dress in the middle of a 1969 interview with Roger Ebert raised more than $100 million for the fight against AIDS over the course of her lifetime.

Phoebe Connelly is a writer in D.C.