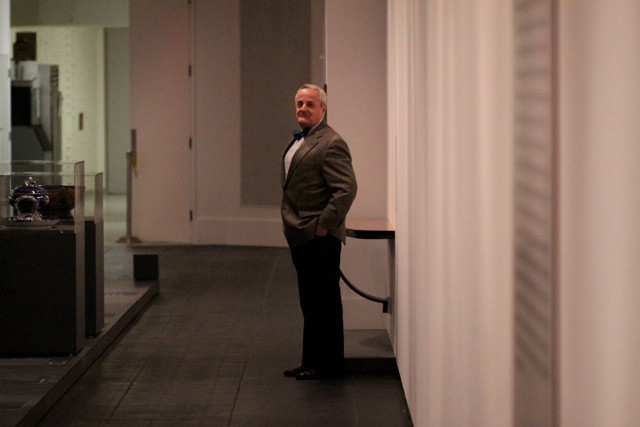

Barry Harwood, Curator of Decorative Arts, The Brooklyn Museum

by Andrew Piccone

Tell me about your job.

I’m responsible for 25,000 objects that were made in the West, that is, European and American. The earliest objects we have are medieval ones from the 14th century and we go up until tomorrow, as I like to say; it’s very much an ongoing collection. I’m responsible for interpreting the objects, doing research on them, and then to display the objects, working with a lot of different people in the museum: conservators, designers, all of the art handlers. You have to coordinate with a whole team of people in order to put objects on display. Even though we have so many, only about 15% are on display. They live in storage, which always makes me sad, because people don’t get to see what we have. The objects are owned by the board of trustees, but it’s in public trust, it’s a public collection. I think the most fun part of my job is acquiring new objects. We acquire objects through purchase, and through coaxing people to donate them. Although sometimes very generous people will step forward and offer things. And so we buy both old objects to fill in the historical story, and we try to buy new objects, figuring out what is going to be deemed important down the line. Right now we are showing a new installation through the end of May called “Thinking Big,” and it is 45 relatively recent acquisitions that the decorative arts department has made. They are all 20th-century objects, and they were all acquired in the last ten years. Periodically, it’s really interesting to show the public the sorts of things we’ve been buying, but to my amazement we’ve acquired over 600 objects in the last ten years that are from the 20th century. This is just 45 of those 600. Contemporary items are real crowd pleasers, and it’s very interesting for me because it’s some of the most important and interesting things we’ve acquired and its great to see the new shape of the collection.

What brought you to where you are now?

I somehow always knew what I wanted to do. When I was a small child I knew I either wanted to run an antique store or teach about history. I always had a sense of wanting to be around old things. I guess I didn’t think about working in a museum until I was in high school when I realized this was the sort of job I wanted. I’m from New York, and growing up we went to museums all the time. Although the funny story is I didn’t come to the Brooklyn Museum until I was at Princeton in graduate school. They took us on a field trip here and I remember asking my mother why we never came to the Brooklyn Museum, it’s such a fabulous place. And she just said to me, ‘Oh, back then nice people didn’t go to Brooklyn.’ She has since been proved wrong. I’ve been here almost 25 years.

How have you seen Brooklyn change firsthand in the last couple of decades?

Well, everyone knows the demographics have changed. I think that the new, younger people of Brooklyn see this very much as their museum. Of course in the early part of the 20th century, before the Depression, when Brooklyn was still expanding a great deal, this was a very lively place, a center for the community. I think the Depression really devastated Brooklyn, and then people started to move away. After World War II, it was the great flight to the suburbs, and that hurt Brooklyn a great deal. In the last 20 years there has been a real return, and a sense that this is Brooklyn’s museum. Though, there are a tremendous amount of foreign visitors who come here. Foreign visitors come here, they open up their guidebooks, and the Metropolitan Museum gets four stars and the Brooklyn Museum gets three stars, and if they’re here for a while they’ll come here.

You mentioned the Met. Are they your museum ‘rivals,’ so to speak?

That’s a complicated story. In Europe the museum systems are really centralized. In France, there is the Louvre; since it’s a small country that is the one, main central museum. However, the United States is so enormous there are important museums all over the country: Chicago, LA, Dallas, and in between. The reason why the Brooklyn Museum is here is because when it was founded Brooklyn was a separate city. Chalk it up to civic pride and everything — they wanted a separate museum. After the end of the 19th century, when all the boroughs combined, I think that the potential of the Brooklyn Museum was diminished a little bit. If it were in any other city it would be the principal cultural attraction. But in New York the museum firmament is so dense. The collections here are really world class. I suppose the Egyptian collection is the most famous on an international scale, but the American decorative arts is really as good as anywhere else. It’s a bit different from the Met’s collection. The Met always says that they’re a museum of masterpieces. At the Brooklyn Museum we always collect a bit further down the food chain. We indeed have masterpieces, but we also have objects that were used by the upper middle class. It’s a much more diverse collection in that way. In some ways it’s more representative of the vast middle class that developed here.

What is your favorite piece in the collection?

Even though I’m in charge of this enormous historical period, I suppose I’m most interested in the period after the Civil War, up to the present. That is when the United States developed the identity that we all recognize today. It was a very exciting time. There was a great deal of immigration. It’s a period where the United States became the principal world power. It was a great center of industry, invention, innovation. I’m most interested in that sense of the growing modernity which developed. The core of the collection here is a group of period rooms, the earliest is a Dutch Colonial house from the late 17th century and the last one is an Art Deco room from a Park Avenue apartment from 1930. We have a very exotic parlor from about 1880 from a house that was on 54th street and it’s decorated in the aesthetic movement style and it was the American view of a Moorish smoking room. It’s very exotic and very dense, pattern on pattern, color on color. It’s a very extravagant room. Even though it’s a whole room, that as an object is my favorite in the collection.

How is the Brooklyn Museum, and the industry in general doing in 2011?

I think all museums are feeling really pressed at the moment. Americans and New Yorkers in particular are incredibly generous. In Europe the museums are supported almost completely by the government, private giving is nowhere near as important as it is here. There’s just not a tradition really of that kind of public giving. Museums here rely on government money, but also private money. The curious situation here is that the City of New York owns the building, and they pay for the upkeep and running the building, the maintenance staff and the guards are all city employees. The professional staff, such as myself, are not city employees, but employed by the board of trustees. Every year the city cuts back the amount of money it gives to Brooklyn, and that’s a serious problem. Corporate funding gets cut back during tough times, and private giving gets cut back too, people feel nervous and insecure. The charitable dollar is one of the first things that goes. It’s still a very difficult moment. The corporate sponsors are only very slowly coming back, but they are. What’s interesting is that private donors didn’t stop giving, but gave at a lower level.

I see you have a Dr. Spock cut-out in your office; are you a Trekkie?

I’ve been a Trekkie from the very beginning. I’ll still watch reruns, I can recite dialogue. My favorite series was “The Next Generation.” I’m completely devoted to the early series, but by the time “The Next Generation” started, the special effects were better, the acting was better, it was just better. I enjoyed the reboot of the film series from a few years ago. I thought it was really enjoyable and well done and really convincing.

If you could have one other job, what would it be?

Oh, hmm, well I do have another job, actually. In addition to being curator I also teach at Cooper-Hewitt’s masters program in decorative arts. I enjoy teaching a great deal. I always say jokingly, when else do I get to hear my favorite person talk for two hours? It is performing; it is a bit of an ego trip. But it’s also a more serious way to pass on what one knows, and what one has learned. It keeps me more active in the field and the contact with the younger people in the field is very exciting. If I could have another career, well, I played violin growing up. I suppose I would have pursued music if I hadn’t pursued art history. I’m very happy with the path I did take. I have lots of acquaintances who are at the point where they are nearing retirement, and I can’t imagine retiring. I’m doing what I like to do, so why retire?

Andrew Piccone is a photographer in New York.