The NFL Negotiates The Apocalypse

Eyes either narrow or widen, depending, and voices come up a tense octave. There’s a certain palpable raising of the drawbridge from the man responding: the question or statement is contemptible, and it is very clearly being held in contempt, and this discussion is going to end just as soon as it can be ended. The reason it doesn’t end right then, right after the word gets said, is that these are professionals, professional football players and smooth spokesmen both. And so the proper responses — “no, not at all”; “that’s most definitely not how we see ourselves” — make their way out and into the microphones and notebooks and early-week assessment pieces. But offense is taken all the same whenever a team or player is described as exemplifying or exhibiting finesse.

Even in the umbrage-powered world of the NFL, the response elicited by the word “finesse” is noteworthy for its intensity and weirdness. Offense is taken even though every NFL team is, in some sense and several facets, a “finesse team,” and even though the good ones are more so than others. “Finesse” means elegant and skillful and clever when used as a noun, and describes a swift use of subtlety as a verb. It is also both a noun and a verb in bridge, as it turns out, but in neither of the word’s common or (improbably complicated and weirdly player-on-your-left contingent) card-related definitions does “finesse” scan as faggoty or soft or un-tough. (Although the fact that there even is a bridge definition maybe does not help, there) The only place that finesse plays as an insult or gay-baity taunt is football, and the only reason for that is that, in the football lexicon, finesse is antonymic to power and therefore the opposite of praise. Describe a player or a team as a finesse team and they will correct you: they are a physical team, they are a tough team. They don’t know what you’re talking about, but they know in their hearts — they can look around this locker room and tell you, straight up and for sure — that there is no finesse in here.

Which is fine or fine-ish, since this particular usage issue is hardly the most offensive thing about football’s jingo-tarded lexicon and also because the league’s wounded linguists are honestly welcome to whatever gets them through the headache-y night of a brutally long season in a punishing sport. And anyway, it’s not unique to them; we get the same sort of thing from the secret sportswriters who cover politics. And in the same way that all that sneering at candidates inclined (so elitistly) towards “nuance” tends to look kind of nauseating once the blunt/direct/plainspoken Manicheans bring their straight-line idiocies to elective office, the NFL is suffering-unto-death from its aversion to the skillful or subtle or un-direct, and an unwillingness to acknowledge any way around a problem but over it. In this case, it’s about money, and labor, and how the NFL’s owners understand the coddled, sharecrop economy in which they participate.

After a year of relentless and relentlessly ridiculous war-talk, the NFL Players Association and the league’s owners are meeting — right now, and for the rest of this week — in a federal labor mediator’s office on the plains of Armageddon. On one side are football players trained to believe, think and speak in the language of power; opposite them are the puffy, tough-talking billionaires of the NFL’s ownership caste, who learned the same stupid language in boardrooms and boarding schools. It’s billionaires against millionaires — a point the president made in dismissing speculation that he’d involve himself in the dispute, right before he went back to determining what kind of cuts in the safety net were the most moderate. The NFL negotiations feature true believers and hard-liners everywhere you look, each rolling out the same smash-mouthy dullardry, calling plays from the same goofy playbook, and avoiding any appearance of finessing anything. Those stubborn things being, in no particular order, just how much money the owners are entitled to make off their teams, how little of that revenue they are entitled to pay to the athletes who create that value, and what broader responsibilities each might have to the other. This is complicated stuff, and neither side seems able, let alone willing, to talk about it. The resulting power-off has been not so much a negotiation as a helmet-to-helmet tackle, over and over, back and forth forever.

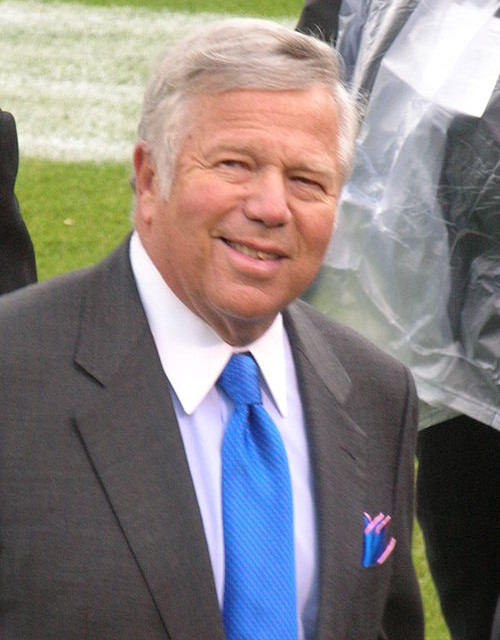

This is the kind of helmet-to-helmet hit of the kind that leaves both parties foggy and writhing on the turf, but the aggressor — the one who “launched,” to use the strangely technical language of the soggy and selective anti-concussion policy that the NFL belatedly put into place this year — would unquestionably be the owners. NFL players are bred as dominance machines, but in the hard-line owners — wild-eyed Galt-grade assholes like Panthers owner Jerry Richardson or doughy boardroom zealots like Patriots owner Robert Kraft — the players are facing a different and differently motivated opponent than they’ve faced before. Richardson is a former NFL player born again as a Hardee’s tycoon and Bush Ranger in the feudal and union-averse Carolinas, and he is prone to Tea Party-ish oratory about “taking his league back.” Kraft, a real-estate magnate and the NFL plutocracy’s most benign public face, bought the Patriots because he grew up as a fan and kept them in New England because he was from there. What the two have in common — besides great wealth, limited patience, personal friendship with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell and a vanishingly small risk of trauma-induced brain injury in their day-to-day lives — is a privileged place among the nation’s sports oligarchs.

Of all the reasons for rich people to buy a professional sports team, profit would ordinarily not rate terribly high. But Richardson and Kraft and every other NFL owner makes money off the teams they own. Just how much they make is a secret, because the privately held NFL teams have (as is their admittedly confusing right) refused to open their books to the union in negotiations; the open books of the Green Bay Packers, the NFL’s one publicly owned team, suggest that NFL teams generate profits in the tens of millions of dollars. They make this money through the league’s $4 billion television deal — split equally between the teams, as is the plutocratic style — and they make it through ticket and luxury box sales and the associated extortionate frippery related to those ticket sales and they make it through renting out the stadiums they (and local tax money and government-authored bond issues) bought. And they make it in part because their employees work on non-guaranteed contracts and also, in part, because they have not as yet had to contribute much to the very expensive post-retirement health care of those employees, who have recently evinced embarrassing-ish tendencies to lose their minds and harm/kill themselves post-retirement, among the other sad misbehaviors consistent with what one would expect from people who had suffered extreme and repeated work-related brain trauma.

Which would maybe make it more sensible if the players were the “launchers” here, driving themselves vengefully — in the self-destructive, head-first manner taught as a fundamental by your big-time football coaches — at the vulnerable heads of the employers who are kind of objectively getting over on them in a bunch of ways. But they’re not. The owners are proposing that the league expand to an 18-game season while simultaneously proposing to take another $1 billion (in addition to the billion they already get) off the top of the league’s $9 billion in revenue for overhead. The latter will shrink the players’ share of the league’s revenues from roughly 58% to a little under 48%, while tacking two weeks of effectively unpaid (and highly dangerous) overtime onto the season. Given how profitable NFL teams already are, given how small a share of those profits players actually see, and given that the players association is expected to concede on at least some of what’s in the last sentence — the 18-game season is seen as a virtual inevitability — it’s hard to see what the owners are so hacked-off about. Yes, costs have gone up and NFL revenues, despite breaking records year after year, have fallen short of the owners’ projections; but profits remain strong, and NFL teams continue to appreciate in value exponentially. Leaving aside the only-in-the-NFL idea that the owners of sports teams — teams that are generally regarded as vanity purchases, and perhaps most charitably seen as public civic goods with decent cash-flow — are somehow entitled to ever-increasing profits, this simply should not be a crisis.

There’s a reason why owners have proven seemingly unable to regard it as anything but that, though. It has to do with the same wrongheaded rich-guy righteousness that saw your more media-savvy plutocrats endeavor (and succeed!) in making public employees with five-figure salaries into the villains of an economic collapse created by financial industry speculators earning ten times that and more, and it also has to do with the permanent-midnight doomsaying that has become the only way the right talks about economics. And of course it has a lot to do with the by-any-means-necessary acrobatics of which even the softest-bodied capitalist is capable when his right to all-you-can-eat everything is challenged.

As with the dim, meatish governors of Wisconsin and Ohio, Karl Rove’s cynical rhetorical signature — accusing the opponent of your crime — has found a strange and sobering new life among NFL owners who are seemingly not in on the bleak joke, and who actually believe this shit. There’s a frank ridiculousness to Richardson and other NFL hard-line owners laying in a multi-billion dollar strike fund — comprised of TV revenues which the league demanded as an advance from the networks, without ever promising that there would be a season to televise next year — while heatedly filing a lawsuit accusing the players of not negotiating in good faith. (That ridiculousness probably has something to do with federal judge David Doty invalidating that agreement, a decision that deprived NFL owners of the wherewithal to weather a lockout and that gave the best hope yet for reconciliation.)

Likewise, there’s a breathtaking cynicism undergirding Jerry Richardson’s exhortation to “take back our league” from the players who do the dirty, concussive work in exchange for less than 60 percent of revenues, but it might absolve him somewhat that he honestly seems to believe that no struggle could be braver or more justified than that of NFL owners against their employees. Just as surely as Scott Walker believes his trollish politicking and crude bullying is brave and unblinking statesmanship, Richardson et al believe that they are making a twilight stand against… well, what?

This is the problem with making a casus belli out of something as simultaneously brutish and opaque as the divine right of the powerful. The broad-unto-blurry ideas at work here — keep what you earn, get what you can get, do as thou wilt, and so simply on — sell easily enough. Put it into practice, though, and the actual all-out pursuit of Every Single Thing looks a lot like madness. That is, it leads to behaviors and ways of understanding that are not just vain or self-interested but actually fucking nuts, which actually make the world warp and twist around its self-interested new axis until everything that is not the individual and that individual’s interest falls into formation with the army opposite, an army that’s just about the size of the rest of the world. It’s a worldview that doesn’t work. It widens every negotiation into an armageddon, brooks no result but the destruction of the opponent, and that’s what it’s doing here in the NFL and there in several states. The rhetoric of the NFL closes off compromise on its own, but this particular problem is deeper. It’s tough to imagine the NFL Players Association — or AFSCME, or anyone — successfully finessing this sort of apocalyptic narcissism.

David Roth co-writes the Wall Street Journal’s Daily Fix, contributes to the sports blog Can’t Stop the Bleeding and has his own little website. And he tweets!

Photo by BrokenSphere.