How to Spot a First Edition

One of the most touching things about Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids is the way the author slips into book-scouting lingo when she describes the knack she had for that enjoyable (and revenue-enhancing) pastime in the late ’60s and early ‘70s:

Not long after, I found a twenty-six-volume set of the complete Henry James for next to nothing. It was in perfect condition. I knew a customer at Scribner’s who would want it. The tissue guards were intact, the gravures fresh-looking, and there was no foxing on the pages. I cleared over one hundred dollars. Slipping five twenty-dollar bills in a sock, I tied a ribbon around it and gave it to Robert.

Smith describes a number of such finds. The mere idea that you could run into a signed Faulkner just wandering around a used bookstore in New Jersey!

It’s worthwhile to know a little bit about rare books — because it’s fun and also because you shouldn’t be letting valuable things slip off into perdition, if you can help it. There are many characteristics that tend to make a book more valuable, but nearly all the valuable ones are first editions. So what is a first edition, exactly?

A reasonably simple question, but it turns out to be one of those deceptively difficult ones, like “What is knowledge?” or “Can cats secretly talk?”: one that even a lifetime of study can never fully answer.

Let’s get on a sound footing by first considering the whole idea of collecting books.

Bibliophilia, taken as a separate pursuit from the mere love of reading (which it may accompany) is concerned with all aspects of books, not only their contents. Bibliophiles like to study their materials and construction, or the whole history of a publishing house, a genre, an author. There’s no detail they won’t pore over. The history of publishing is chockablock with romantic stories: the charm and brilliance of designers like Eric Gill, say, or the literary sensitivity of Max Perkins (soon to be played by Sean Penn in a movie, apparently). Whole collections are built around such things as these. And collectible books can become tokens rich with personal associations, of course. Patti Smith found one of the rare Ace paperbacks of William S. Burroughs’s debut as “William Lee” at a bookstall near Forty-Second Street one night with Robert Mapplethorpe. She never sold it, she says.

The study of a particular copy will somehow set the collector’s heart beating a little faster: how close is it to that rare state, “pristine,” still looking absolutely new despite its great age, in a fresh, glossy, clean wrapper free of even the slightest little tear, and inscribed by the author to his favorite mistress, who happens to be the model for the heroine of the story? That would be ideal. Or maybe it’s an agreeably raggedy old thing, published by the book club a century later: “spine ends bumped, with chipped corners, cocked, hinges cracked and some foxing.”

For those of us who have always collected books in order to read them, the two might scarcely be worth telling apart, so long as they contain the same words in the same order. To a collector, however, who sees each copy of a book as a specific, significant instance of that book’s history on this earth, the difference may be as vast as that between the Hope Diamond and some wretched thing the cat dragged in. So, on to business.

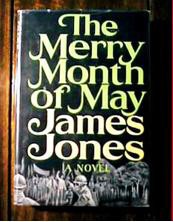

Here is a quite nice-looking book, in a decent dustjacket (or in Knifecrime Islandese, “dustwrapper”) in a protective mylar cover. (The Highsmith company of Wisconsin is a great library supplier where you can buy these at a good price and in small quantities. Yay Wisconsin.)

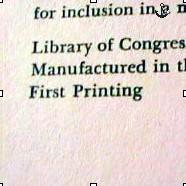

Much of the information you’ll need for identifying a first edition is contained on the copyright page, which can be found on the reverse side (“verso” they sometimes say) of the title page.

The number series (also “number line” or “printer’s key”) found on the copyright page of many modern books is a valuable clue. Unfortunately, the subject volume lacks this feature. When the number “1” is present, that is an excellent sign and really almost always means a first printing. Irritatingly, some publishers such as Random House (in certain years) omit the “1” and begin with “2,” even on the first printing.

If you’re lucky, you will see the generally credible words, “First Printing.” A first printing in collector’s terms means the first printing of the first edition, so that when you see those words your research may well be over. The words “first edition” and “first printing” are often used more or less interchangeably in the book world, though really they shouldn’t be. A printing is a single print run. An edition refers to the whole set of what were once printing plates. When any corrections or amendments are made to the original plates, then you have a second edition. If a dozen separate printings are made off the first set of plates, though, only those copies from the very first printing are of significant value; this is true, generally speaking, even of highly collectible books. You may have the twelfth printing of the first edition, but that doesn’t mean you have a “true first.” Almost always, it’s only the very first printing that has collectible value. (With older books, this whole business gets quite a bit trickier, since number lines didn’t come into general use until well into the twentieth century. It sometimes takes quite a bit of research to get hold of all the pertinent details.)

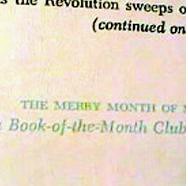

The agreeable term “First Printing” can also be found occasionally in a modern book club edition, in which case the book club will have just ordered some immense number of copies right off the first print run.

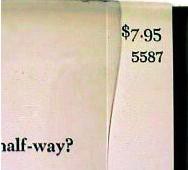

This very book contains a message indicating that it was a selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club. That may mean that this is a book club edition, printed in the zillions and therefore utterly without value; or it may mean that the author Mr. Jones was fortunate enough to have secured an agreement with the BOMC in advance of the original trade publication of his novel. In these cases, you must check out the dustjacket, if present. Book club editions, most commonly, do not have a price on the inner flap of the dustjacket. But this copy has the price… a good sign.

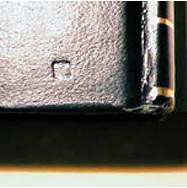

Also, you’ll find that book-club editions are commonly marked with a blind stamp — that’s a small embossed dot or square or other recessed mark on the lower right corner of the back cover. There are probably exceptions to this (there always seem to be!), but blind stamps seem to be found only on book club editions. No blind stamp here … excellent.

(Personally, I find book club editions make great reading copies, and you don’t have to feel so guilty when you take them into the bathtub.)

It’s a good bet that this is, in fact, a genuine first edition. Worth, according to comparisons from the various search services such as Abebooks, maybe thirty or forty bucks in this condition.

The real trouble is that even today, there are no standards by which all publishers routinely identify their own first editions, and there are immense numbers of publishers. Not to mention which, publishing houses tend to change their methods over the years, and exceptions and errors are made constantly. Even experts are continually fooled as to the authenticity of various books purported to be “firsts.” All the little details that go into identifying the first edition of a particular title are called “points,” or “points of issue”; if you ever get into collecting a particular set of titles, you’ll very soon be up on all the relevant ones. Here’s a good one, just to be getting on with: the true first of Infinite Jest has got William Vollmann’s name misspelled on the dustjacket blurb (with just one “n”).

Keep in mind too that most books, even most first editions, are without collectible value. Only the stuff that turns out to have lasting interest appreciates over time. Really the best way to learn how to identify valuable first editions is to handle a lot of books with a view to learning how to do so. There are several excellent basic books on collecting commonly used by experts, notably Collected Books: The Guide to Values by Allen Ahearn and Patricia Ahearn, and The Pocket Guide to the Identification of First Editions by Bill McBride is a good portable reference. Also recommended: the murder mysteries by John Dunning, Booked to Die and The Bookman’s Wake. These feature the detective Cliff Janeway, a bibliophile and book dealer whose descriptions of book collecting are fun to read and full of useful details. Plus, there are murders!

Please be aware that a substantial percentage of the books for sale online are wrongly described. (That is a knife that cuts both ways, of course, because quite often less knowledgeable sellers may not quite know what it is they’ve got.) Careful study will reveal that many, many dealers, in some cases more than half those offering a given title, have not bothered to figure out what the earliest printing was, but instead merely pop the magic words “first edition” into their listings, either out of unwarranted optimism or mere laziness, or outright chicanery. If book lovers do the necessary homework, it will no longer pay those lazy bums to be so sloppy.

A Visual Dictionary of Commonly Used Terms

Cocked (spine slanted)

Foxing

A blind stamp

Lower spine end bumped

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like A Gentleman, Think Like A Woman.