"87th Precinct" (1961-1962)

The TV treatment of Ed McBain’s beloved 87th Precinct novels got whacked.

I once worked with a guy who told me this, with unblinking seriousness, when I sheepishly confessed to liking Metallica: “Metallica deconstructs masculinity.” I wasn’t sure if this was true, but I loved it: it sounded both smart and crazy, seemed dazzlingly counterintuitive, and absolved me of some of my embarrassment by conferring value on the sentence’s somewhat naff subject. In fact, I liked the statement so much that in the intervening couple of decades since I first heard it, I’ve tried to match its latter two words with other unlikely subjects in the art and entertainment worlds. For example, “Evan Hunter deconstructs masculinity.” Sure, it lacks the satisfying crunch of the original, but it has the advantage of being true.

Evan Hunter was born Salvatore Lombino in New York City in 1926 and died in Connecticut in 2005, and in that span he wrote one hundred–odd novels and a clutch of screenplays, most famously The Birds for Alfred Hitchcock. But the books for which Hunter is best known are credited to Ed McBain, whose name you will have seen on the covers of the 87th Precinct crime novels in your dad’s den. Your dad has good taste: the 87th Precinct novels are crisp, funny, and keenly plotted; Hunter was devoted to showing the detectives’ technique, supplying forensics, and not wasting the reader’s time.

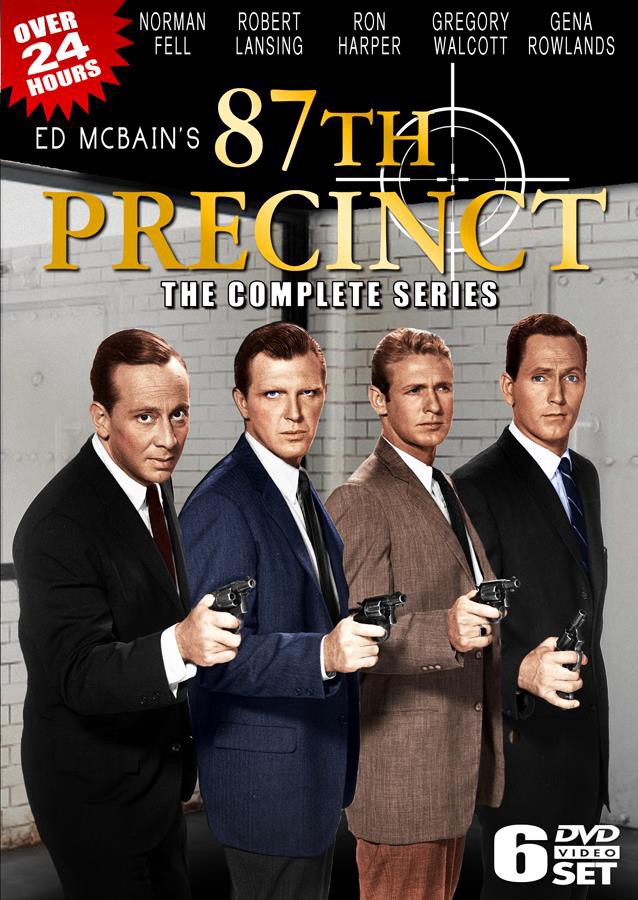

The books are also the basis for a rather marvelous, utterly forgotten black-and-white crime drama that ran on NBC for a single season, from 1961 to 1962. “87th Precinct” doesn’t seem to be streaming anywhere; I got a copy of the DVD through my Boston-area library, which somehow borrowed it from a library in Lawrence, Kansas. Like the McBain novels, “87th Precinct” revolves around a handful of detectives working out of a standard-issue building in a gritty metropolis. Robert Lansing plays the head dick, Steve Carella, in a way that’s hard-boiled but not ossified. (Lansing had practice: he played Carella in 1960’s The Pusher, based on the McBain novel of that name.) Carella’s second bananas are Bert Kling, a young buck played by Ron Harper, whose tutelage under Lee Strasberg served the actor well; Meyer Meyer, the long-suffering family man, played by Norman Fell — Mr. Roper to you if you’re a child of the seventies — who turns in a subtly Jewed-up performance; and dedicated bachelor Roger Havilland (an asshole in the McBain novels but cleaned up for television), played by Gregory Walcott with a Southern accent that — in the series’ only unsolved mystery — keeps disappearing.

The thirty episodes are economical and muscular, and there’s not a dud among them. Some were based on stories by pros like the just-out-of-the-gate Donald E. Westlake, but the most reliable source of material was the 87th Precinct books — Hunter himself turned a couple into teleplays. Given this, “87th Precinct” can’t help but carry the mark of Hunter’s liberalism, made plain in his books and in interviews, which is what transforms the show from a solid crime drama into something a little bit heroic for its time.

“87th Precinct” is almost exhibitionist in its sympathy for the luckless community the detectives serve, made up of kooky old-timers, people with accents, kids playing unsupervised on city sidewalks, and adults on their second chances. You won’t often find the 87th’s detectives rushing to catch a crook at a Park Avenue palace. This precinct was serving — in a phrase that would have made Carella suspicious — multicultural America.

If the pasty, blue-eyed Lansing doesn’t immediately conjure the novels’ pointedly Italian-American star, there’s no glossing over his background in the scripts. In one episode, after Carella meets an older Italian couple — the owners of a burgled shop — he tosses off a line in Italian to gain their trust. In another, he’s trying to get a suspect’s name out of a club owner who says, “It’s one of those long, crazy I-talian names. Seems like it starts with a C,” to which the detective replies, “You mean something like Carella?” In “Occupation, Citizen,” Carella meets with a locksmith — a “Hungarian refugee” — who may be able to identify a perp. When Carella tries to pronounce the locksmith’s name — it’s Czepreghi — the man smiles and says, “I’m going to change it when I get my citizenship papers. I mean, we’re going to have a baby. You can’t hang a name like that on an American kid.” Carella says, “Don’t change it. It’s a good name.” Funny how Hunter, who had adopted a de-ethnicized name, kept his protagonist’s stripes visible.

I-talians, Latinos, and various ambiguously accented characters were joined by Asian characters played by certifiably Asian actors — hardly a sure bet in 1961 and 1962; as late as 1964, Marlo Thomas was cast as a Chinese mail-order bride in an episode of “Bonanza.” At some point while I was tearing through “87th Precinct” episodes, I figured at this rate I might even see a black actor. I racked up several, including a cop played by Bernie Hamilton (later of “Starsky and Hutch”) and an unbearably cute toddler who says “I was robbed!” while sitting on Meyer’s desk, the precinct’s rest stop for neighborhood eccentrics.

When the kid’s parents — a smiling, well-dressed black couple — come to claim their little prevaricator, I became convinced that the team behind “87th Precinct” was informing white viewers, two years before television brought them the March on Washington, that black people were part of their world, so deal with it, you racist shitsacks. Having said that, the lost-toddler-on-the-desk scene also works as a reflection of the show’s commitment to realism. In this episode, a toddler tests Meyer’s patience. In another, Lansing grumbles about breaking in new shoes. Everybody’s home life intrudes on their work. Everybody bitches about their meager paychecks. These short, naturalistic-seeming sequences, all inconsequential to the case up for cracking, offer a level of set dressing anathema to the crime genre at the time. As Ron Harper says of “87th Precinct” in a DVD extra, “It wasn’t Sergeant Friday.”

The nattering among the series’ four principals neutralizes the detective story’s archetypal macho posturing, and at one point the show addresses it head-on. In “Line of Duty,” which Hunter wrote specially for the series, Kling kills his first criminal, and it turns out to be a teenager, which undoes him. A preoccupation with male grief is characteristic of Hunter’s work and the lynchpin in his 1959 novel A Matter of Conviction, at the end of which a troubled teenager’s remark, “Crying is for cowards,” is answered this way by the prosecutor protagonist: “Crying is for men, too.” When Carella tells Kling’s worried girlfriend, “The first time I killed a man I went home and I bawled like a baby,” it splits the seams of his Ronald Reagan–ish rectitude.

“87th Precinct” doesn’t avoid all the tropes of the era. Some judo chops are less convincing than others, and a few of the less seasoned guest stars should have joined Ron Harper in Lee Strasberg’s acting class. But overall, the guesting actors are a welcome procession of favorite midcentury faces, some on their way up (Peter Falk, Dennis Hopper, Leonard Nimoy, Robert Culp, and Gena Rowlands, as Carella’s deaf wife) and one on her way to Washington (Nancy Davis Reagan). By the time John “Gomez” Astin showed up, I thought there weren’t any beloved character actors left, but suddenly, there was a pre–“Beverly Hillbillies” Nancy Kulp, screaming her head off about a corpse.

In the graveyard for shows canceled before their time, “87th Precinct” must have one of the dumbest causes of death. An online source says that its ratings suffered from its being up against CBS bulwarks “The Danny Thomas Show” and “The Andy Griffith Show,” but in his DVD extra, Harper reports that “87th Precinct” had sturdy ratings and ended because its producer, Hubbell Robinson, went to another network and NBC’s pooh-bahs didn’t think the program could continue without him. Harper says he thought “87th Precinct” had years of life left in it, and I agree. Imagine what an Italian-American gent, an all-American boy, a grumpy Jew, and a lapsed Southerner could have made of the decade’s social issues to come, each new challenge parading up the precinct steps and taking a seat in the chair at Meyer’s desk.

In 2010, there was a news item about how Lionsgate TV, overseen by Steve Buscemi and Stanley Tucci’s Olive Productions, was working on something called “87th Precinct.” I’ve read nothing else about the project and can only surmise that it fizzled. For now, the television successor to “87th Precinct” remains “Hill Street Blues.” Hunter, who truly was the father of the modern police procedural, took issue with that show, telling an interviewer in 1998, “I really don’t think ‘Hill Street Blues’ was an homage to Ed McBain; I think it was a rip-off.” He was even moved to consult a lawyer to see if there was grounds for a suit. “Without even a tip of the hat,” Hunter griped. “Had the creators said somewhere that it was inspired by Ed McBain, I’d feel a little better about it.” Jeez, what a crybaby.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.