What Can Confession Mean Now?

The determined forays of hallowed Western faith traditions into the digital-media world rarely produce a non-embarrassing outcome. There are your teen-themed “Bible-zine” translations. There are your evangelical trade shows. There are your media churches. But the recent news that the Catholic Church was launching a quasi-official confession app on the iPhone was something else again — and not just because it got snapped up in the related Maureen Dowd column-generating software.

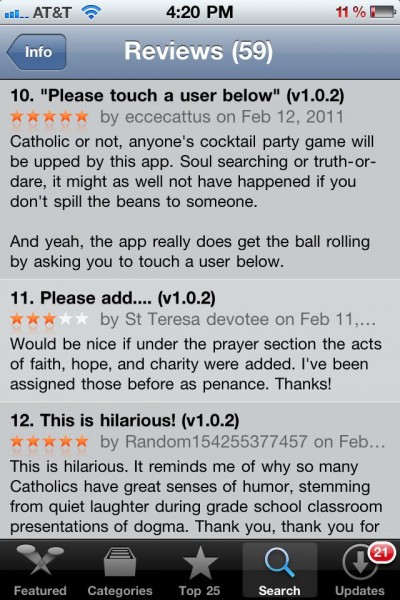

To be fair, the app — the brainchild of a pair of entrepreneurial Indiana-based Catholic brothers, Patrick and Chip Leinen — is not designed to supplant the traditional rite of confession, spoken in anonymity to a real-life priest sequestered in a box. It’s more in the nature of a confession aid — a customized digital enounter tailored to the special needs of a particular sinning demographic. “A priest won’t have the same examination as a teen girl or a married man,” Patrick Leinen told the Catholic News Agency. “You will get something unique to you.” A scalable examination of the human conscience may not yet prompt a boom in digital contrition — at least not until it’s somehow customized further to work on an Angry Birds platform — but it’s something of a formal breakthrough for a faith tradition that hasn’t exactly made “user-friendliness” a watchword. (One also assumes that if the Church-sanctioned app solicits a confession of sexual abuse from a member of the clergy, it will trigger a Mission Impossible-style immolation of app, phone and — who knows? — user.)

Being no strangers to the hierarchical cast of Catholic devotion themselves, the Leinens cite the authority of the papal bureaucracy — namely, the directive from Pope Benedict XVI calling for greater engagement with the social media platforms favored by today’s youth. The Leinen brothers also took pains to win the imprimatur of South Bend Bishop Kevin C. Rhodes, and collaborated on the finer points of the app’s graduated sin-inspection software with a pair of priests, Thomas G. Weinandy, the executive director of the U.S. bishops’ Secretariat for Doctrine and Pastoral Practices, and Dan Scheidt, pastor of Queen of Peace Catholic Church in the nearby Indiana town of Mishawaka.

Still, for all this ex officio punctiliousness, one can’t help feeling that a confession app is a bit off-base. For one thing, it’s aimed at generating a profit, costing $1.99 per user. Has the senior Church hierarchy really forgotten that a mere six hundred years or so ago the open retailing of priestly forgiveness furnished a central grievance of the Reformation?

More troubling still is the question of anonymity. Yes, we are assured, the security protocols of the confession software are sound, but there’s a more fundamental reason that iPhone apps fall under the generic rubric of “social media” — users generally employ them in complete indifference to their surroundings, further denaturing the increasingly porous cultural boundaries that separate out public and private conduct. While the app may ultimately land a wrongdoer in front of a duly solemn confessor in the designated sanctum of a church, completing a subjective moral inventory isn’t something that’s meant to be done during some dead time on a conference call, or while you’re impatiently scouring the departure board at Grand Central Station.

In other words, it’s probably best that the buildup to confession be inconvenient, with a minimum of media distraction involved. According to all manner of Christian moralists, divine judgment is a harrowingly solitary affair, and one reason that the priest in the confession box is concealed — apart from ensuring full anonymity to both parties in confession — is to symbolize the impersonal nature of god’s judgment. Without that screened-in generic symbol of divine authority, Church fathers reckoned, confessors would be apt to conceal their mortal sins out of a sense of personal shame. Initiating that same process via an iPhone app, by contrast, is a bit like trying to administer extreme unction via a Netflix stream. There’s a reason that a fully mechanized vision of the confessional was trotted out as a joke, after all, in Woody Allen’s futurist farce Sleeper (back in 1973, that is, where the innovation seemed laughably remote, and Allen was still capable of executing convincing jokes on film).

Viewed from the logic of the new information age, a digitized confession is but another step in the broader diffusion of the vital human stuff of soul, intelligence and selfhood — the cyber-utopian, new-machine dynamism that Clay Shirky and Chris Anderson hymn (in different keys, to be fair) before the mirror each morning in their own rote and priestly fashion. Still, for all the soothing appurtenances that attach to way-new digital faith, it’s hard to see how the duly wired believer can significantly advance behind the dour Catholic counsel of Blaise Pascal: “All men’s miseries derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.”

Chris Lehmann has been our religion columnist.