When Sharks Cry

There’s a fair amount of crying in business

Not long after Mikki Bey started pitching the Sharks on her eyelash extension business, the waterworks started. Seven million people watched at home as her eyes, the area of her expertise, turned into muddy rivers. She was defending her business and, by extension, her dream. It was a vulnerable, passionate act of crying, and, for real estate mogul and “Shark Tank” investor Barbara Corcoran, one worthy of admonishment.

“The minute a woman cries, you’re giving away your power,” she said. “You have to cry privately.”

Capitalism, by nature, works best when it’s cold and impersonal. “Don’t cry for money,” Kevin O’Leary, the show’s resident Simon Cowell, once intoned when the dudes of Mr. Tod’s Pie Factory got weepy. “It never cries for you.” But something about “Shark Tank,” a reality program replete with bombastic music and crushing insults, makes it one of the most emotional shows on television. Entrepreneurs pitch their companies to multi-millionaire investors; the results can either transform or destroy their lives.

“People get so emotional during ‘Shark Tank’ because it encompasses making dreams come true,” Lori Greiner, one of the “sharks” and a prolific inventor known for investing in retail products, told me. Somewhere out there, there’s still an American Dream. People start businesses in garages; they steal time from their day jobs to make products. They borrow money from in-laws and roll the dice on second mortgages because they believe in themselves. They don’t want to spend another day working for a clueless boss. They never say no to fifteen minutes on national television.

I asked Robert Herjavec, who is a technology mogul and one of the show’s longest-serving “sharks” and the “son of an immigrant factory worker,” why the Tank gets people so worked up. “These entrepreneurs are putting their futures on the line,” he told me. “They sacrifice their time and money — giving their heart and soul to develop their idea. ‘Shark Tank’ is an incredible platform that tells the story of a business in a way that’s relatable and inspiring.”

Social media shows fans crying in droves, moved by the plight of producer-vetted entrepreneurs, stung when their delusions get aired out. Others suspect crying is a negotiation tactic, a last ditch effort to goad the Sharks into throwing money at bad companies. I asked a viewer named Christine what about “Shark Tank” made her weep. “Mostly the fact that people take such big risks,” she said. “And to have them pay off is such a great reward for all their fear, hard work, and sacrifice.”

For Nick Lutke, a devoted “Shark Tank” fan and self-proclaimed connoisseur of reality competition shows, tears are directly tied to deals. “It’s heartbreaking to see their dreams crushed and it’s heartwarming to see their hard work rewarded,” he told me. “I’m an empath, so I get very invested in people and their struggles. Watching people overcome doubt and have their visions confirmed and celebrated is moving enough to elicit tears.”

One of the show’s most infamous crying jags was courtesy of Taya Geiger, co-founder and CEO of Scratch & Grain Baking Co. She lost it after Mark Cuban asked how she’d become so driven — an innocuous question to viewers, but one that resurrected memories of growing up with a drug-addled single mom. “Mark Cuban knew exactly what to ask me,” she said. “To be honest, the producers were jumping up and down when they saw me start crying because I did not tell them any of this stuff. I purposely hid everything about my past because I didn’t want it to be a public thing. They know what they’re doing. They know the emotional questions to ask.”

Geiger was also very pregnant at the time. “I actually had my baby less than twenty hours after we filmed that segment,” she continued. “It was an emergency kind of a deal, five-and-a-half weeks early. We took a plane ride home early, and had I not done that, it would have been a whole different outcome. So, yeah, part of my tears were hormonal.”

One risk of crying on “Shark Tank” is that it becomes part of your company’s narrative, thanks in part to incessant reruns on CNBC. Eventually, “Shark Tank” could fill a role akin to “Seinfeld” and “Friends” — an audio-visual narcotic primed for late-night comfort. We’ve seen every pitch; we know every quip by heart. Tears become an act of iconic vulnerability or ugliness, depending on who you ask. Some viewers never let the presenters forget.

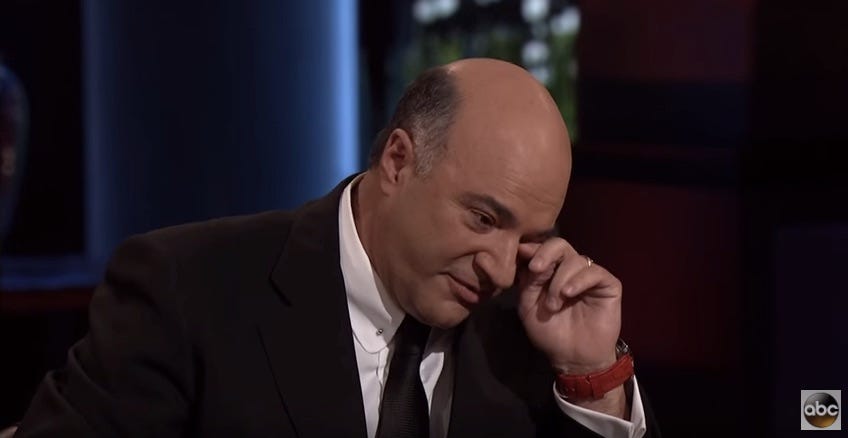

Ultimately, Scratch & Grain boarded that flight with a deal. Their investor? Barbara “there’s no crying in business” Corcoran. And while Corcoran has (by my count) only wept once on the show, it’s not unheard of for Sharks to join in on the waterworks. I like to think of the Sharks’ row of five as representing a progressive scale of softness. Cuban, on the far left, has an estimated $3 billion in the bank, over six times the wealth of his nearest peer (O’Leary). He never cries. And like Corcoran, usually seated to his right, his facial expressions maintain a hint of disgust toward entrepreneurs who don’t keep their composure. Kevin O’Leary sits dead middle, the most frequent catalyst for tears and most dismissive investor on the show, yet secretly he’s kind of a baby.

Greiner, “the Queen of QVC,” sits second to the right. She takes risks on personalities rather than products and isn’t afraid to let emotions play a role in her investments. Then there’s Robert Herjavec on the end, softest of Sharks, ready to let loose at mention of his father or a timely rags-to-riches appeal.

When I asked Mark Cuban why the show elicited such emotion, he concluded the reason was its polarity. “Watching people see their dreams come true or possibly crushed can bring anyone to tears of joy or empathy,” he said. There’s little to no space in between. Success and failure result in the same tears, whether from the entrepreneur under bright lights or us watching under covers in the dark. “Shark Tank” provides a novel view into the real people behind corporations. As Geiger pointed out, companies aren’t just General Mills or nonsense words favored by the tech industry. “That’s why ‘Shark Tank’ is so popular,” she said. “It humanizes business.”