The Mysteries of Ambrose Bierce

Hello, would you like to buy something weird? Hammer Time is our guide to things that are for sale at auction: fantastic, consequential and freakishly grotesque archival treasures that appear in public for just a brief moment, most likely never to be seen again.

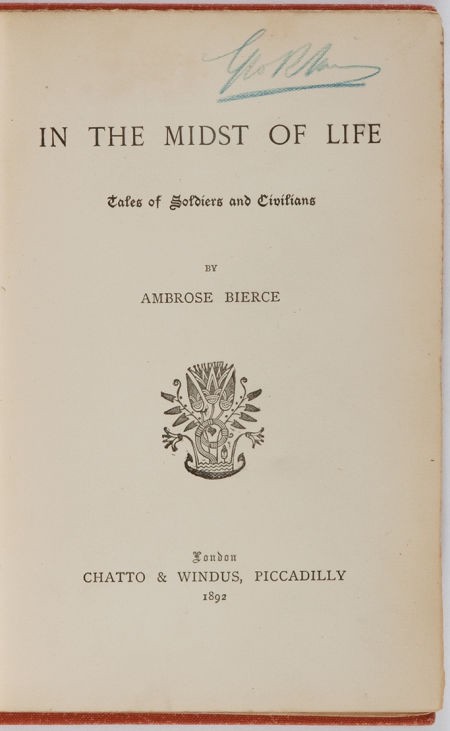

If novelist Carsten Stroud has $53 or so to his name, we hope he hurried over to Heritage Auction house for their most-recent sale of books and autographs. Under the hammer: a British first edition of Ambrose Bierce’s In the Midst of Life: Tales of Soldiers and Civilians, which contains “An Occurrence at Owl Creek,” a short story Stroud recently listed as one of his “Top Five Horror Classics.”

Stroud is in good company. Kurt Vonnegut proclaimed “An Occurrence at Owl Creek,” which was first published in The San Francisco Examiner in 1890, to be the greatest American short story. It has inspired an opera, movies, television adaptations, and various narrative forms with irregular time sequences.

And yet, it’s hardly the most interesting thing about a man whose personal motto was “Nothing matters.” At the age of 71, Bierce supposedly penned the following farewell to his niece, Lorna:

Goodbye. If you hear of my being stood up against a Mexican stone wall and shot to rags please know that I think that a pretty good way to depart this life. It beats old age, disease, or falling down the cellar stars. To be a gringo in Mexico — ah, that is euthanasia.

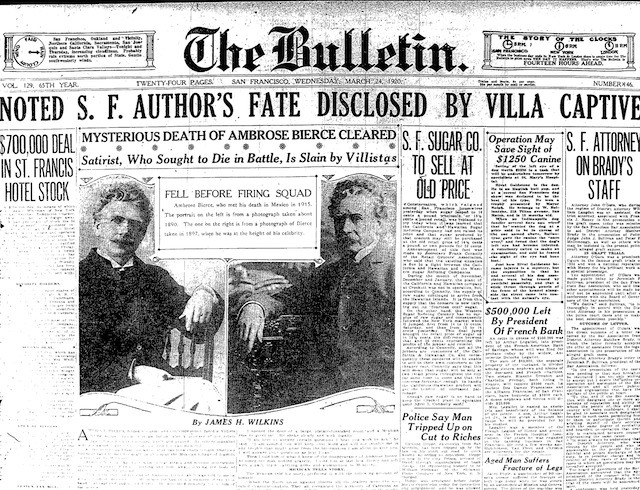

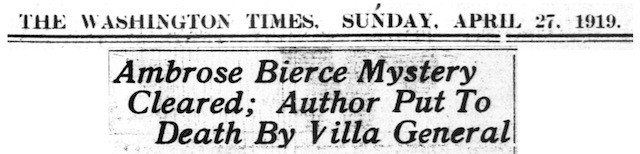

He would never be seen again. By the time Bierce entered Mexico by way of El Paso, the country was two years into the decade-long revolution. In Ciudad Juárez, he must have witnessed the Robin Hood-like tactics of “Pancho Villa,” then provisional Governor of Chihuahua. The two reached some kind of agreement, and Bierce joined Pancho Villa’s army as an observer, but after December of 1913, he completely vanished.

The circumstances under which Bierce died were debated by his contemporaries, and the discord has not lessened with time. Some argue he was critical of Pancho Villa, while others cite his poor health and advanced age. No single theory has been substantiated to satisfaction, but a very thorough attempt was made by a retired priest. After collecting oral histories in Sierra Mojada, Coahuila, James Lienert concluded that Bierce was executed by a firing squad in 1914, and paid for a headstone to be engraved. (translated to English)

Very trustworthy witnesses suppose

that here lie the remains of

1842 Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce 1914

a famous American writer and journalist who

on suspicion of being a spy

was executed and buried in this place

Such a dispute is fitting for a searing critic whose nickname was “Bitter Bierce.” At 15, he left his poor, literary parents and twelve siblings (all with names beginning with the letter “A”) in hopes of becoming a “printer’s devil.” He soon abandoned the apprenticeship for the Union Army’s 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment, and fought in the Battle of Shiloh. Bierce was discharged after sustaining a head wound, but he rejoined General William Babcock Hazen’s expeditions in the Great Plains.

After the Civil War ended, Bierce made his way to San Francisco and resumed a career in print. His editorials often appeared in local newspapers, but it was his polemic satire that frequently put William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner at the very center of controversy. After President William McKinley died from complications associated with gunshot wounds, Bierce was fingered as instigator. Rival newspapers, along with then Secretary of State Elihu Root, called into question a poem Bierce had penned after William Goebel, the only governor to be assassinated in office, was killed.

The bullet that pierced Goebel’s breast

Can not be found in all the West;

Good reason, it is speeding here

To stretch McKinley on his bier

Despite naming the president in the concluding stanza in 1900, Bierce maintained that his intentions were to express national anxiety, not welcome another murderous act.

While the poem certainly aroused public interest, Bierce’s best known satire can be found in The Devil’s Dictionary, a reference book published as The Cynic’s Word Book in 1906. He defines a conservative as “a statesman who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal, who wishes to replace them with others.” An idiot is just one member of a “large and powerful tribe” who “sets the fashions and opinion in taste, dictates the limitations of speech and circumscribes conduct with a dead-line.” While most of his definitions focus on politics, with a nod to those driven by self-serving motivations, Bierce was also preoccupied with the domestic sphere, defining intimacy as “a relation into which fools are providentially drawn for their mutual destruction.”

He was likely referring to his own marriage to Mary Ellen Day, with whom he had three children. In 1888, Bierce left his wife after discovering a collection of suggestive letters penned by an admirer. They would divorce in 1904, after they had buried both of their sons: Day committed suicide in 1889 after an amorous gesture was rejected, and Leigh was an alcoholic who died of pneumonia. Mary Ellen herself died in 1905, and their daughter Helen lived until 1940.

While Bierce’s personal items rarely come to auction, most of his published works are still in print.

Alexis Coe’s work has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, The Hairpin, SF Weekly, The Toast, and other publications. She holds an MA in history, and was a research curator at the New York Public Library. Follow her.