For Your Own Good: Chipping Away at 'Roe'

The Supreme Court’s historic Roe v. Wade decision turned 38 last week, and regardless of one’s ultimate view of the issue, the legal right to abortion on demand is clearly in the throes an awkward middle age.

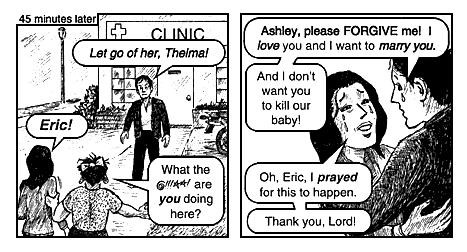

This year’s Roe anniversary coincides with the indictment of Philadelphia abortion provider Kermit Gosnell on eight counts of murder. Gosnell appears to have been the sort of unscrupulous abortion mill operator you’d find in a Jack Chick comic — an answer to the many fervid prayers of pro-life activists keen to make the public abortion understand as murder in the most brutal and forceful terms. When state inspectors suspended his license and closed his clinic down in February, they noted that he performed abortion in any term of a pregnancy, heedless of basic health, safety or sanitation measures.

They reported finding “blood on the floor and parts of fetuses in jars” — though as the Philadelphia district attorney’s office notes, these conditions prevailed only in the high-turnover main facility of Gosnell’s clinic, which catered chiefly to low-income and immigrant pregnant women in the middle Atlantic. A separate part of the clinic, designed to serve better-heeled suburban white patients, was safer and cleaner, the DA reports. Gosnell himself got rich in the process, even though he was never actually licensed as an OB-GYN, charging about $3,000 per procedure, and making $1.8 million; the DA’s office had found $240,000 in cash in his home.

The grand jury report on the indictments spells out the routine butchery of the Gosnell operation in a wealth of horrifying, heartbreaking detail. Seven of the eight murder counts involve him (or one of his all-too-often untrained assistants) ending the lives of viable fetuses — another routine malpractice alleged in the indictments involved Gosnell blithely disregarding or misrepresenting the gestation of a fetus, so as to sidestep Pennslyvania’s Abortion Control Act, which forbids abortions after the 24th week. Gosnell or his fellow clinicians would terminate these more mature fetuses by crushing their spines or slitting their throats. The one non-fetus count in the indictment is a wrenching character study unto itself: In November 2009, a 41-year-old patient named Karnamaya Mongar died after an unlicensed employee of the clinic administered too much anesthesia to her. Mongar had arrived in the United States just four months earlier together with her husband, after spending almost twenty years in a Nepalese refugee camp; the couple had been expelled from Bhutan along with thousands of other dissidents for taking part in pro-democracy protests, and Mongar’s husband, Ash, had just found work at a Virginia chiecken factory. After a Virginia clinic refused her an abortion because Mongar was in her second trimester, she was referred to Gosnell’s operation; there, a clinic’s aide performed an ultrasound, and while Gosnell signed a form stipulating he’d met with Mongar beforehand, he hadn’t bothered to, instead leaving an aide who was by all accounts his least competent anesthesia hand to administer what the indictment. The initials of both Mongar and her daughter, who drove her to the clinic, were affixed to consent and waiver forms, even though Mongar spoke no English and her daughter scarcely spoke any. Mongar was a diminutive 4’11” and weighed 110 lbs, even well into her second trimester; a competent physician would have taken that into account with her anesthesia; but then again, a competent physician would have actually met with his patient and not signed a form falsely representing that he had done so. Over a grueling six-hour ordeal that sought to chemically induce cramping and labor, Mongar was administered heavy doses of sedative to be kept asleep. As the grand jury report tersely notes, “repeated injections of strong narcotics, administered in accordance with Gosnell’s standard procedure, killed Mrs. Mongar.”

Clearly, there is nothing for pro-choice activists to cheer in this grisly saga. And critics of the absolutist, no-slippery-slope defense of reproductive rights — “abortion on demand, without apology,” as the slogan has it — are seizing on Gosnell’s story as a limit-case of where this reasoning leads. The terms of engagement, as always, are the entirely arbitrary trimester-scheme of fetus viability that the Roe decision bequeathed to the partisans as its own sort of scripture. In the worldview of choice absolutism, as Slate’s Will Saletan writes…

…there’s no moral difference between eight, 18, and 28 weeks. No one has the right to judge another person’s abortion decision, regardless of her stage of pregnancy. Each woman is entitled to decide not only whether to have an abortion, but how long she can wait to make that choice…. You can argue that what Gosnell did wasn’t conventional abortion — he routinely delivered the babies before slitting their necks — but the 33 proposed charges involving the Abortion Control Act have nothing to do with that. Those charges pertain strictly to a time limit: performing abortions beyond 24 weeks. Should Gosnell be prosecuted for violating that limit? Is it OK to outlaw abortions at 28, 30, or 32 weeks? Or is drawing such a line an unacceptable breach of women’s autonomy?

Yes, the Gosnell case does raise these well worn issues anew — though one obvious rejoinder to Saletan’s rhetorical questions is that it’s not too much to ask that the state competently administer both later-term abortion limits and standard medical regulation and licensing protocols.

Still, Gosnell’s grotesque brand of malpractice, in the Mongar case especially, also touches on the emerging new legal and moral battleground of the abortion debate. As Mother Jones writer Sarah Blaustein notes, abortion foes are increasingly citing the well-being of the mother as the basis for restricting and — so they hope — eventually outlawing the procedure all together. South Dakota’s controversial 2005 bill virtually banning abortion was redrafted to stress the alleged long-term mental-health harm that abortions wreak on women who endure the procedure. And the U.S. Supreme Court, in its 2007 Gonzales v. Carhart ruling upholding the congressional ban on later-term abortions, employed a version of the same rationale. The majority opinion, written by Justice Kennedy, conceded that the proposition holding that abortions harmed the mental health of patients was “unexceptionable,” even though “no reliable data” actually upholds that view. In lieu of such data Kennedy cited the anecdotal testimony presented before the South Dakota legislature — even though, as Blaustein observes, that legislation itself contained no exception for the mother’s physical health.

Such acrobatics point up the rhetorically overloaded character of the seemingly never-to-be-resolved moral debate over abortion. For pro-life absolutists, the fetus in gestation possesses a sort of emotional supra-life, despite so much of the legal debate’s preoccupation of just when a fetus can be said to be defined as an independent human life. In this righteous scheme, the crocodile tears shed over the alleged mental health perils the procedure wreaks on would-be mothers almost entirely crowds out the actual plight of people like Karnamaya Mangar, who was no “culture of death” libertine. She had two daughters in addition to the one who drove her to Gosnell’s clinic, and a grandchild as well; in all likelihood, she and her husband reckoned an unplanned pregnancy was an economic burden they couldn’t fathom facing in a strange land on a chicken worker’s salary. And there’s no rhetorical percentage for the anti-abortion crowd to make the debate about victims such as her, since an outright abortion ban would vastly increase the volume of unscrupulous and unlicensed providers like Gosnell in the marketplace, and thereby multiply the body count among women seeking outlawed abortions.

Meanwhile, for pro-choice absolutists, the hard-fought legal goal of women’s bodily autonomy is the higher good that tends to suborn other moral or legal claims. As Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote in a stinging dissent to Kennedy, the Carhart opinion rested on “an antiabortion shibboleth for which [the Court] concededly has no reliable evidence…. This way of thinking reflects ancient notions about women’s place in the family and under the Constitution — ideas that have long since been discredited.”

Still, one can’t help but thinking how little meaning such notions of choice and autonomy wound up having for Mongar, especially after she’d paid so heavily for agitating for democracy in her own homeland. The pat, passionately held certitudes on both sides of the abortion debate fall oddly silent before a system of health care that deliberately ensures a higher quality of basic care for the more affluent — and as the Philadelphia DA observed, even a shitheel like Gosnell knew enough about the real workings of the class-segmented health care market to reproduce its logic in his own facility.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the debate over universal health care is prey to the same theatrically gnat-straining brand of moral absolutism — or what amounts to the same thing, the wan subject of difference-trimming resolutions from clerics that are most notable for their eagerness to sidestep the culture-war landmine of abortion rights. The Gossnell indictment doesn’t note what religious beliefs Mongar may have held, but one thing seems clear: She was a collateral casualty of a sclerotic public discourse that, in its patent disregard for making choice a nonlethal good in a fiercely privatized medical marketplace, can fairly be described as faithless.

Chris Lehmann is our religion columnist now