The Supreme Court Justice Who Shot A Senator

by Zach Dorfman

If, like me, you are dispirited by our national political climate, you may occasionally entertain the sense that you are witness to an era of unprecedented moral debasement. Creeping oligarchy, the re-emergence of an atavistic paleo-conservatism, the slow death-wheeze of the fourth estate, the rise of a relentlessly cheery techno-utopian Gatsby class — we’ve got a lot working against us. But if you think our era is defined by its high concentration of professional reprobates, or that the stakes for our republic are particularly high, you might find lukewarm comfort in the story of Judge David Smith Terry.

In the pantheon of salty, contemptuous bastards in American politics, not many can out-do Terry, a bowie-wielding, ardent-pro-slavery Texan with a volcanic temper, who rose to become Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court in the mid-nineteenth century. Like some shadow-character from Blood Meridian, Terry’s life mixed tragedy, vulgarity, absurdity, and spite in equal measure.

Terry was a nationally infamous figure in his own day — no mean feat, in a time when travel back East often meant a seaward departure via the Golden Gate, and an overland trip through the jungles of Panama. There was a wealth of contemporary writing about the judge during the nineteenth century, most of it highly tendentious, portraying Terry as either a rough-and-tumble all-American hero or Lucifer instantiated. (“Blood, blood, blood, seems to be the only substance in nature capable of slaking the thirst of this man-beast,” wrote the San Francisco Bulletin.) But there was a steep drop-off in interest in Terry after his death. In fact, the most recent book about him, a blithely sympathetic biography, David S. Terry of California: Dueling Judge, by Albert Russell Buchanan, a history professor at UC Santa Barbara, is itself sixty years old.

Born in Kentucky, and raised in Mississippi and Texas after his father abandoned the family, Terry fought in the Texas Revolution and, later, in the Mexican-American War. He studied law and headed, like so many other self-aggrandizers then and now, to California to make his fortune during the Gold Rush of 1849. It was there that he developed his reputation as a bit of a stabby hothead, inclined to settle legal or personal disputes with his giant knife, which he always kept sheathed at his side. (Once, in a fit of pique over an unflattering piece about him published anonymously in the Pacific Statesman, he reportedly broke a cane over an editor’s head, then waved his knife him, shouting, “Now, damn you, give me that name or I’ll take your life!”)

Terry’s reputation did not stymie his political ambitions. After a few failed attempts at running for office, Terry was elected in 1855 to the California Supreme Court as a member of the Know-Nothing Party at the age of thirty-three. Most other men would have settled into the kind of staid, stable life promised by a prominent civic position. But Terry’s penchant for violence was rivaled only by his comic capacity for high dudgeon.

In 1856, the year after he was elected to the state Supreme Court, Terry stabbed a man in the neck during a street brawl in downtown San Francisco. The man was a member of the San Francisco Vigilance Committee of 1856, which had recently overthrown the local government in response to its lawlessness and corruption. Terry was arrested, imprisoned, and tried. When Terry’s victim failed to succumb to his injuries, the judge’s release became more politically palatable for Vigilante leaders, who were under pressure to hang Terry for his crime, but did not wish to incur the wrath of the Federal Government. Terry’s speedy trial concluded under highly irregular circumstances, and he was acquitted.

In 1859, at the Democratic convention in Sacramento, Terry launched a blistering attack against U.S. Senator David Broderick, whom he blamed for blocking his nomination to a second term on the state Supreme Court. Broderick, a former tavern owner, was raised in New York City and schooled in Tammany Hall machine politics; he was also a leader of the abolitionist wing of the party. During his convention speech, Terry accused his enemies in the party of being “the personal chattels of a single individual,” belonging “heart and soul, body and breeches, to David C. Broderick.” Understandably displeased, Senator Broderick chastised the Chief Justice as a “damned miserable wretch” to a friend of Terry’s during breakfast a few days later at a San Francisco hotel.

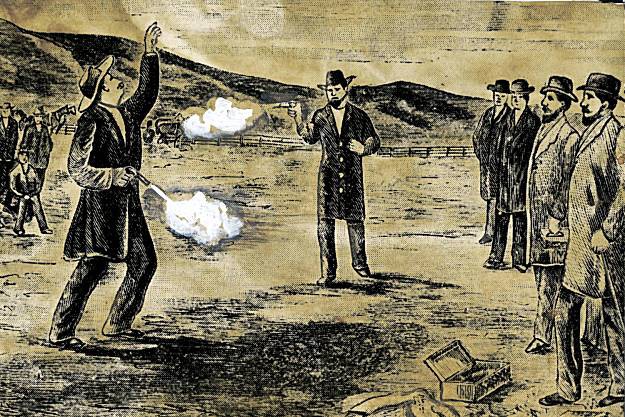

Terry could not countenance this affront to his honor, and subsequently challenged Broderick to a duel. On the cold, misty morning of September 13, 1859, the two men squared off in a verdant ravine just over the San Francisco city line, near the south side of Lake Merced. Broderick fired first, and missed. Terry did not. The senator hung on for a few feverish days, and then died (but not before he claimed, on his deathbed, that he was murdered for opposing “slavery and a corrupt administration”). Fairly or not, the duel was widely seen thereafter as a proxy battle for the pro- and anti-slavery constituencies in California, and across the entire country.

Terry temporarily abandoned politics. He made his way to Nevada, attempting to stake a claim in gold country. When it became clear that the South would secede from the Union, Terry was swept up by the passions of the day. In 1863, he snuck out of California — Unionist officials there kept a close eye on him, since his sympathies were well known — to return to his native Texas to fight for the Confederacy during the war. He was wounded at the Battle of Chickamauga, and subsequently escaped to Mexico with a group of Confederate dead-enders when the cause was very clearly lost. After an aimless three-year period in Mexico, Terry returned to California, and resumed his relatively prominent place in local life in Stockton. He seemed to mellow with age.

Terry’s first wife, Cornelia Runnels, had always been a moderating influence on the judge, but he did not choose wisely in love again. After Cornelia died in 1884, he married a boisterous, vivacious woman twenty-seven years his junior

named Sarah Althea, who was a client of his. Althea was already locally infamous when Terry agreed to represent her: she claimed (falsely, it appears) to be the secret ex-wife of U.S. Senator William Sharon of Nevada and demanded her share of the senator’s considerable wealth. Terry felt the presiding judge, Stephen J. Field — who was also a sitting federal justice of the Supreme Court (and a Unionist Lincoln appointee) — was prejudiced against his client (his wife). The judge ruled against them. In the melee after the decision, Terry assaulted a number of court officials, and was sent to jail for six months.

Terry did not forgive this perceived injustice, and his begrudging attitude led to his rapid demise. On August 14, 1889, roughly six months after his release from jail, Terry happened to travel with his wife from Sacramento to San Francisco on the very same train as Judge Field. Terry spied the Supreme Court Justice during a stop at a stationhouse dining room in the San Joaquin Valley, and purportedly rushed at the judge and slapped him upside the head. Terry was promptly shot to death by a U.S. Marshall; he was sixty-six. Sarah Althea returned for a brief time to San Francisco, but soon came completely untethered, and was sent to a sanitarium in Stockton, where she spent the next forty years of her life.

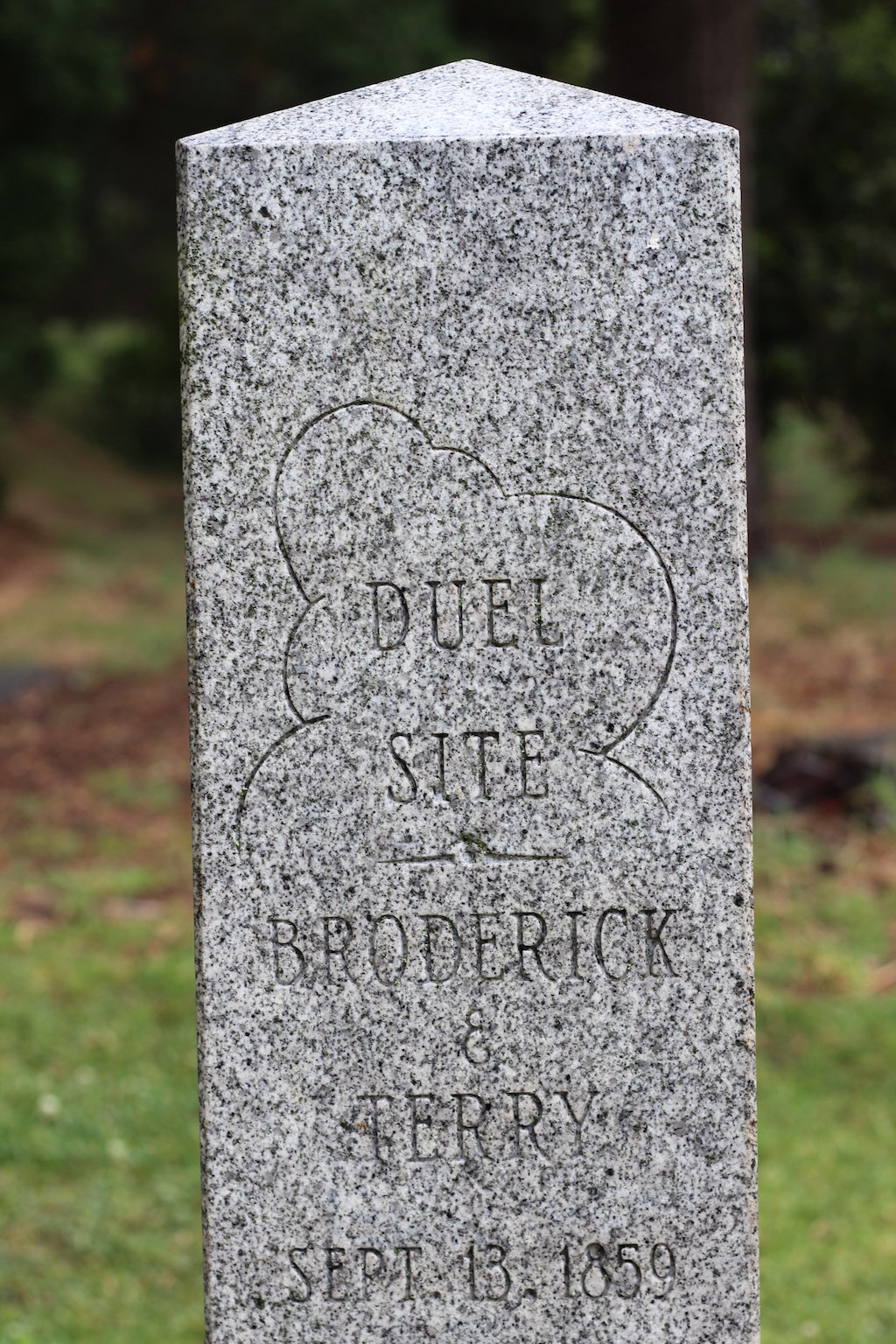

With a little effort, you can still visit the Terry-Broderick duel site today. If you head toward the ocean on John Daly Boulevard — passing the Chipotle and Home Depot and T.J. Maxx — you will eventually reach the neat, manicured upper-middle-class Westlake neighborhood, the very one made famous for its “ticky-tacky” houses. Hidden between two of the homes is a little wood-chipped path that leads to the site.

You can only access the park from the south. To the north, a ravine raises steeply to the lake. To the west is an exclusive country club, to the east is an even more exclusive one; the golf courses of both are visible through the eucalyptus. There are blooming wild calla lilies, and cigarette butts, and fresh coyote scat. In the center of the clearing there is a small obelisk commemorating the site. A little farther down the path are two older stone pillars marking the exact spots where Broderick and Terry stood when they shot at one other, maybe twenty steps apart.

The Terry-Broderick duel si

te was among the first recognized by the state as worthy of official commemoration, and designated as such in 1932. California — and the Bay Area in particular — tries to perpetuate a myth of continual reinvention, but the site provides a small bit of tangible proof that America’s venomous nineteenth-century politics transported themselves all the way out to the Pacific.

Thankfully, organized violence is no longer considered an acceptable way to settle domestic political disputes. We will probably never see a character like Terry, with his George Wallace-meets-Crocodile Dundee vibe, again. But the robust berserker streak in American life? That, as the last six months have made abundantly clear, is here to stay.