Claims Adjusters of The Third Kind

Who is alien abduction insurance really for?

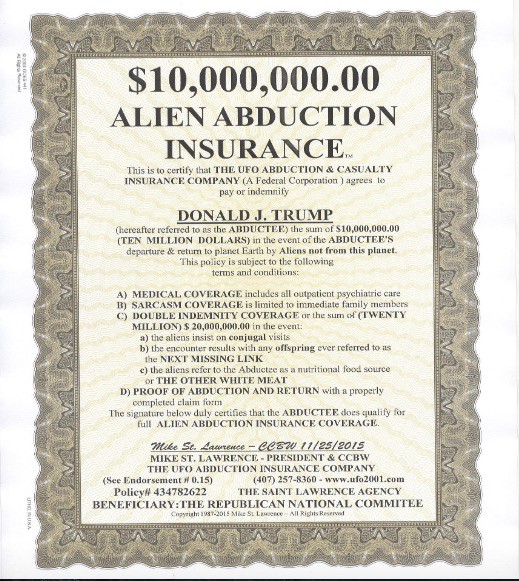

In Altamonte Springs, a sleepy suburb of Orlando, Florida, there’s a little insurance outfit, the Saint Lawrence Agency, that will sell you a bizarre product: “Alien Abduction Insurance.” For a low one-time premium of $9.95, company president Mike St. Lawrence offers $10 million in coverage for medical or psychiatric care and physical or emotional damages resulting from any future extraterrestrial kidnappings that take you past earth’s atmosphere and back. He even offers a double indemnity if your alien kidnappers leave you (man or woman) impregnated, insist on returning to molest you repeatedly, or refer to you as a potential food source. He doesn’t care if you’ve been abducted before; he’ll sell the same policy to anyone who inquires. There’s just one catch: if you want to make a claim on that coverage, you’ll need to prove that you were in fact abducted, ideally in the form of a signed statement by your abductors.

The Saint Lawrence Agency’s offering is patently absurd, written tongue-in-cheek and functionally impossible to claim. Yet now and then, someone genuinely afraid of abduction will find this insurance, only to discover that it’s poking fun at his or her fears. And St. Lawrence isn’t the only agent who’s ever offered alien abduction insurance; at least one other policy may have sucked true believers into the joke to their detriment. Parody policies like this one are an unsettling quandary about the ethics of business, humor, and our perception and treatment of people with “absurd” beliefs.

St. Lawrence wrote his abduction policy in 1987. He’d been selling $10 million “reincarnation insurance,” which he meant as a spoof on the decade’s yuppie materialism. If life insurance is about protecting your loved ones after you’re gone, he said, then “reincarnation insurance is all about insuring yourself when you come back for the next life,” if you can prove you’ve returned. Then one night he and his brother caught a TV interview with an abductee, Whitley Strieber, promoting his new book, Communion. His brother said he should make the emerging UFO mania of the era his next vehicle for satire. So he cracked out the policy in a fifteen-minute sitting.

St. Lawrence, who sees himself as a consumer advocate, described the policy as a spoof of the insurance industry, where many firms obfuscate details that could frustrate buyers and a select few straight up prey on fear and knowledge gaps to sell crap. “That’s the point I’m trying to make,” he said. “You’ve got to be careful as a consumer that someone’s not trying to pull the wool over your eyes.”

To make sure his product doesn’t become a massive irony, St. Lawrence takes pains to present his policy as a novelty item. His website, which looks like it was built on Angelfire circa 1996, is peppered with dated jokes, like the fact that he’s backed by the inventor of the Japanese junk bond, Dr. Hu F. Oh. He calls the gold-embossed certificate that comes with each purchase a unique gift, and makes a conscious effort not to sell to anyone he thinks doesn’t understand the joke. “Most of the people who purchase this policy don’t do it for themselves,” says St. Lawrence. “They do it for someone they know who might have an interest in the subject matter. It’s a really cool gift to get them if, and only if, they’ve got a sense of humor.”

But not everyone is so scrupulous. In 1996, Simon Burgess of London’s Goodfellow Rebecca Ingram Pearson (GRIP) put out his own alien abduction insurance. The exact timing is a little unclear, but St. Lawrence is convinced that it came out days after an article on his Alien Abduction Insurance Company ran in a British paper. “I get really bent out of shape when I talk about that Burgess guy,” he says. “I’d like to get my hands around his neck and… hurt him [laughs].” I reached out to Burgess at his most recent financial venture, British Money, but he did not respond to answer questions about the origins of his policy or anything else — including the status of these policies despite the fact that GRIP is no more. But Burgess does have a history with other parody insurance policies — against Loch Ness monster attacks and virgin births, to name a few — and his alien abduction policy did differ from St. Lawrence’s in some details, such as charging an approximately $150 yearly premium for an average of $1.5 million in coverage.

St. Lawrence got bent out of shape by the GRIP policy not just because it copied him, but also because he felt it led people to confuse him with a manipulative firm. In 1996, Burgess claimed he’d paid out $1.6 million to an abductee who came to him with a transparent alien claw, but later acknowledged this was a publicity stunt. A year later, it was reported that he’d insured the alien cult Heaven’s Gate for $1,000 with $1 million in coverage per person months before almost forty of them committed suicide in 1997. The company briefly stopped selling the policy, but had resumed sales by late 1998 at least after greed got the better of them, as Burgess told an SFGate reporter that year. By one account, GRIP wound up selling at least 30,000 policies and making at least £4 million. “I’ve never been afraid of parsing the feeble-minded from their cash,” Burgess said to the same SFGate reporter.

Most people who believe in alien abductions aren’t likely to buy into such prodding and impossible policies. However, according to Susan Clancy, a cognitive psychologist at Harvard and author of Abducted: How People Come to Believe They Were Kidnapped by Aliens, stunts like Burgess’s can validate the fears of those most troubled by the prospect of abduction. There are always people too desperate for assistance to read the fine print who end up purchasing policies that will ultimately slap them in the face when they want to make a claim. Even policies like St. Lawrence’s, which is more obviously presented as a joke, can screw with this population, she said. “You think you’re going for help and you find that the person you’re going to for help is actually making fun of you?” muses Clancy. “It sucks.”

To date, St. Lawrence has sold about 100,000 policies. He claimed there was only one instance of a misunderstanding, when an old man bought a policy from him only to realize ten years later that it was all a joke. He says he did the honorable thing and refunded him $19.95 (the old rate for a policy). However it’s hard to say how many people may have been turned away or disappointed. It probably doesn’t help that he admits to having paid out on two policies, which drew a fair amount of publicity. At least one was to a true believer whom St. Lawrence says still had a sense of humor and used the publicity to make light of a real fear. The man eventually presented him with a letter from a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor claiming that an object he’d removed form his body after an abduction wasn’t made of any earthly metal, a proof St. Lawrence accepted. He then agreed to pay out $10 million — in the form of $1 per year over 10 million years or until the man died. However, he lost track of him down the line.

Within business ethics, it’s functionally legitimate to insure almost anyone against almost anything. For fun and publicity, cruise lines have taken out policies against sea monster attacks and hotels against damage caused by their poltergeists. St. Lawrence has even been investigated by regulators in Texas and Florida. They affirmed that, so long as he’s clear about the humorous intent of the impossibility of a full payout on the scheme, what he’s doing is absolutely permissible — officially ethical.

Even Clancy admitted the number of people who could possibly be burned by these (and most other) parody policies is very low, especially in relation to those who’ll benefit from the satire. She estimated that while up to ten percent of Americans believe alien abductions are possible, only one percent believe they happen, and just a small subset of those people live in actual perpetual fear that might drive them to seek legitimate insurance. For any product, there’s always acceptable risk, she stressed. “But in the field of psychology and psychiatry,” she said, “we’re very worried about the issue of harm. So even if it harmed only one person for every thousand who got a [laugh] out of it, I’d still have ethical concerns.”

St. Lawrence stands by the humor, value, and legitimacy of what he’s doing. He also fulfills his legitimate duties as the purveyor of a novelty product. But sometimes existing ethical norms and regulations fall short of a full understanding of the effect a product can have on a population — especially a tiny population we’re used to freely mocking.

It’s impossible to create a regulatory system that fully mitigates harm to consumers, at least without becoming unduly censorious. Still, one has to wonder whether Burgess would have joked so freely about bilking the “feeble-minded” and marketed his policies so legally-yet-cavalierly if he’d actually known an abductee as a person rather than a joke. Or whether St. Lawrence should have made a greater effort to track down the folks he’s paid out to in order to understand the long-term effects of his products. There’s human value in contemplating absurd insurance policies beyond the initial laugh factor. But for most people, all of this is a little too far out there to give a flying fuck about. And so it flies.