Snakes and Ladders

On Allen Frantzen, misogyny, and the problem with tenure.

“Brain tumor?” the direct message read. We speculated about personality-altering illnesses. I repeated the conversation with other friends, other colleagues. It is not ethical to talk like that. Speculating about another person’s health is indefensible. But what can you do when an academic hero turns out to be, or to have become, all of a sudden terribly stupid?

Allen J. Frantzen is a medievalist, now retired. He’s an emeritus professor of Loyola University in Chicago. He is sixty-eight years old, and in 1990, he published a book called Desire For Origins: New Languages, Old English, and Teaching and Tradition, which sits by my bedside. It’s in the permanent pile (which is next to the reviewing pile, separated by a house plant), because it’s one of those books I think is so good I want it within arm’s reach all the time.

Many people find Old English remote, dull, and boring. Desire For Origins interrogates how that came to be, and Frantzen manages the unusual feat of climbing outside his own field. It’s comparable to the work Edward Said did for cultural representations of “The East” in Orientalism, what Johannes Fabian did in Time and the Other for anthropology.

Frantzen has also contributed remarkable work to the youngish field of queer medieval history, with books like Before the Closet: Same-Sex Love from Beowulf to Angels in America. His work is undoubtedly progressive, which is why recent revelations were so stunning as to lead to speculation about personality-altering illnesses.

Follow the internet trail to Frantzen’s personal website, and you’ll find a series of misogynistic screeds peppered with the most hackneyed and useless men’s rights activist jargon you could imagine. It was uncovered by other medievalists last year, and I came across it after Jeffrey Cohen, a professor at George Washington University, tweeted about it:

Allen Frantzen (<– medievalist) is an embarrassment to medieval studies. http://www.allenjfrantzen.com/Men/femfog.html

Frantzen’s reputation first began to shatter within the medievalist community, and ended up as far as the pages of the Chronicle of Higher Education, even Jezebel. The precise page Cohen links to in his tweet has been deleted, but the language used in it, specifically the term “femfog,” sparked ongoing widespread hashtag ridicule.

In a blog post at medieval internet concern In the Middle, Cohen reproduced a section of a now-deleted page of Frantzen’s site, summarizing “femfog”:

Let’s call it the femfog for short, the sour mix of victimization and privilege that makes up modern feminism and that feminists use to intimidate and exploit men … I refer to men who are shrouded in this fog as FUMs, fogged up men. I think they are also fucked up, but let’s settle for the more analytical term. These may might not be feminists but as they wander through the mist of politics and polemic about women, they feel like they should be feminists. They think feminism is good for everybody and they want to be nice to women … My aim in this RP essay is to help you clear the fog of feminist propaganda. Grab your balls (GYB) and be the man you want to be.

A search of #Femfog on Twitter turns up results both funny and deadly serious, and there’s going to be a scholarly panel on it at this year’s big medieval conference in Leeds.

Frantzen espouses ‘masculinism,’ and presents faux-academic arguments for rejecting feminism wholesale as a kind of hegemonic delusion (the aforementioned femfog). He uses MRA terms like “red pill” and “compulsory feminism” and refers to the supposed “fog of WAW (Women are Wonderful) feminism pumped out by the media and politicians.” He cites data in a bizarre parody of scholarly rigor, footnoting and dividing his argument into sections, then writes in the second person.

Like some kind of malevolent advice columnist, Frantzen teaches the would-be ‘masculinist’ to counter his feminist friend’s arguments by suggesting a reading list. “You don’t need to read the whole of these books,” he says:

My bet is that the first few chapters will kick your ass, and that’s all you need. If at any data-related point the feminist challenges you (“That’s not true,” or “I don’t believe that”) check her (or his) credentials. Do this by asking a question: “What have you read about this? Do you have other information, or is that a hunch or perhaps your reaction to a point of view or some data you have not heard before?” Chances are good they will not have data. Press on.

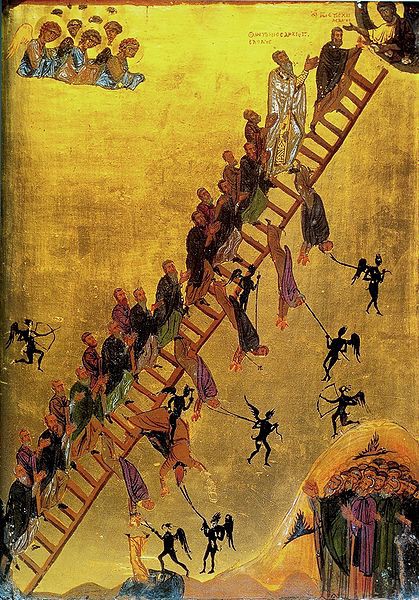

I’m not sure what the strict definition of “hero” is in today’s world, but the author of a book that I keep on a bedside table must be mine. This particular hero has turned out to be a cartoon villain. Medieval literature is usually more subtle than that: fortune’s wheel, which dictates the rise and fall of kings and emperors, turns slowly. It doesn’t spin, or unexpectedly explode. I don’t really have the strength to unpack everything that Frantzen wrote on his site. He’s gay, does that matter? I don’t know. It’s mostly very sad.

The medieval studies community has reacted in a calm and collected way to this nasty event. I’m not worried about the discipline, which is led by ferocious women and brilliant human beings of all genders and identities. I am worried, however, about a workplace in which the tenured, particularly men, are exempt from the kind of character scrutiny to which ordinary employees, especially women (cis, trans, or otherwise), are subjected to in almost every other profession.

In a blog post about Frantzen, Cohen said, “Even as I write an email arrived telling me that I am being ‘extremely unprofessional’ for condemning this writing.” Where is the outline of professionalism for a high-achieving professor and why can’t anybody show it to me? Did tenure protect Allen Frantzen? Tenure means different things depending on context: there’s the tenured professional, then there’s the tenured social individual.

Tenured professors can get fired; immunity from disciplinary action is a myth. Having tenure just means that, if your department wants to fire you, they have to do it in a very slow, well-reasoned, well-proven way. Not all tenured professors are untouchable despots. Cohen is right that, in one sense, the it isn’t the “the profession or its structures” which are to blame. He emphasized “that Frantzen was a lifelong misogynist who carefully kept himself in check until after retirement — so he knew tenure would not protect him all that much with his MRA views.” Still, Cohen says, this is a conversation that we could have had long ago. So, why didn’t we?

From my perspective (far lower down the academic ladder), a tenured professor’s behavior is not subject to sanction, under almost any circumstances, because of the weighting of power in the hierarchy of academic relationships. Not every academic who has hit on, harassed, or propositioned me has been tenured or published influential work, but most of them have. The power that those men have is not derived from their position in HR terms: it’s derived from their position in community terms, the extreme concentration of power that holds up the tenure throne.

Everybody wants to impress a titan in their field. I remember once staring into my coffee, looking at the bubbles at the edge, realizing that a man I had yesterday thought was a god had grabbed my ass while his wife was in the room, not even that far away. What did I do about it? Nothing, including re-evaluate his scholarship. I’ve talked about it with a few people. But he’s fun, and his work is so good, and he’s so senior. There’s nothing substantial there. What would I take to his department? I’ve got nothing. His character isn’t subject to scrutiny; his research is.

Academia accepts the substitution of scholarship for character. This is a bug, not a feature. Cohen pointed out that that tenure provides “the potential for intellectual isolation,” in that it rewards “solitary achievement over collaboration, pioneering over making together . . . and it is easy to drift into some scary places without reality checks to bring you back.”

When we study Animal Farm in middle school we learn that power corrupts. But we can be more specific than that — it’s the trust element of power that corrupts, in the academic context. Peer review is based on trust, teaching is based on trust, tenure is based on trust. Trust is the substance that begins the corruption, and it corrodes when it comes into contact with vulnerability (or hatred, or whatever is eating Allen Frantzen).

So, what are we left with, now that Frantzen has posed a bunch of unanswerable questions then scuttled off into retirement, beyond interrogation? We have a reminder, I suppose, that very clever people can harbor pockets of extreme dullness within their brains. Intellects can be archipelagic. Frantzen’s misogyny also endorses some of my own decisions. Working at the bottom of the academic ladder can be lung-crushingly frustrating. The people at the bottom hold the whole thing up and, if they want, the people at the top can swoop down and abuse you and never even wobble.

I explained all this to a friend over a beer the other day, and it dawned on me that I was free. Not free of the need to grind for money or to work hard, but free of that particular ladder, that particular weight on my chest. I never saw the joy in freedom before. I preferred captivity, because its crush felt loving. But now it’s just me. I don’t have to worry about being ‘extremely unprofessional,’ because I don’t have a profession, except what I’m doing right now, giving voice to the new weightless feeling that Frantzen accidentally pointed out that I had. Not all fogs lift, but some evaporate just as soon as you look around.

Josephine Livingstone is a writer and academic.