New on DVD: The Human Tautology, or, The Branding Centipede

by Matthew Abrams

When the first announcements surfaced on the Internet in the late summer of 2009, it sounded like a low-budget, energetic, insane Japanese special-effects flick, a la Yoshihiro Nishimura, of Mutant Girls Squad and Tokyo Gore Police semi-fame. A couple festivals in midnight or horror series and it could head to DVD, where it’d get passed around by Takashi Miike fans and brought up on forum threads by gorehounds playing that game where they try to out-cite each other as to who’s seen the most outré flick.

It’s on DVD now, but the path wasn’t what anyone expected a year ago. Some months down the road from those first blips, April and May of 2010, a significantly larger chunk of the Internet than originally expected was abuzz about The Human Centipede: First Sequence. Cracking the rusty shackles of the horror and underground sites, it hit the MSN front page, right there by Betty White talking ‘SNL’ with Jay. Not even under the ‘WHAT THE…?’ section, but right there in ‘CELEBS & GOSSIP.’ It’s not hard to see why The Human Centipede is such an unmistakable brand: because it’s an unmistakable concept.

Some will be amused, some nauseated, but few will deny its audacity. I’d warn about mild spoilers, but I’m not going to give away the ending, and other than that, it’d be like warning that I was going to reveal, in a discussion of Spider-Man, that the human protagonist takes on arachnoid qualities at some point in the story.

You already know that in the film, a mad doctor attaches three people together surgically in a centipedish, dodecapedal arrangement. Here’s the spoiler: The Human Centipede does in fact contain a sort of human centipede. This is revealed in the trailer, to remove any question that the humipede is hypothetical, or unaccomplishable, or metaphorical. But why show it in the trailer? The title is your sell, the hint, a verbal equivalent of that shadowy glimpse of partially draped bodies on an operating table. People (okay, a fairly few people) are going to want to see the thing realized, and these are the ones that would shell out ten bucks or place a furtive order OnDemand.

Common wisdom, both dramatic and marketing, says: keep the thing out of the trailer. For a low-budget indie horror film, that title is plenty to reel in your target audience (though they’d also have turned out for alternative titles: Dr. Heiter’s House of Horrors, or Three Corpses: White, or maybe Eat Shit and Die!) but the uninterested demographic of non-horror viewers and people who involuntarily shake their heads when using the phrase “torture porn” will let it slide without note. Without context, The Human Centipede is an eccentric title, but it’s not more inherently pause-giving than The Wasp Woman, or The Kiss of the Spider Woman, or Mansquito. But a strange thing happens when the trailer reveals it, like a two-and-a-half-minute short film following the hint-glimpse-revelation structure standard for nonstandard-monster movies.

When the trailer buildup culminates not in “Only in theaters,” but in the clear display of the thing, the film is reduced to a kind of tautology, an exact one-to-one correlation (title: Human Centipede, content: Human Centipede), and the combined entity becomes some type of self-contained memetic jokery, like SNAKES ON A PLANE. Hey guys, did you hear about THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE, are you gonna see THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE? It’s about THE HUMAN CENTIPEDE. Seeing the trailer is seeing the movie, and people rightfully feel entitled to comment, since they’ve pretty much seen the whole thing.

And on from there to the next person in the word-of-mouth chain. The admittedly brain-grabbing title/concept obliges repetition: you can’t hear it without the urge to tell someone else about it, whether in giddy, can-you-believe-it glee; offended, can-you-believe-it indignation; or baffled, can-you-believe-it incredulity. Even the most bothered are compelled to pass it on, if only to get it off their chests and out of their heads.

It’s a distinct, unambiguous marketing identity, but it also removes the actual film (and thus the need to see it) from the equation. The premise is the title is the trailer is the film. The fact that the unfailing word-of-mouth is largely Internet-transmitted qualifies The Human Centipede as viral-but as with biological viruses, not all filmic viruses are equal. (Some biological viruses pass through the air, some through casual contact. Some, fittingly, are transmitted through the fecal-oral route.) An opposing example: Cloverfield’s press pointedly avoided showing the monster: viral, but left people wanting to see it. The Human Centipede showed the monster at trailer’s climax: viral, no need to bother with the movie, unless you need that extra badge of honor, like a Three Wolf Moon t-shirt, to show your dedication to the bit.

A projectionist in

hit the internet in June to show off a tattoo of the centipede diagram used in the film, stretched across the tops of both feet. When was the last time you saw a Jia Zhangke tattoo? But you can find Keyboard Cat ink in seconds flat. I’m not judging anyone’s taste, but it’s less plausible that the guy found any real merit in it, and more plausible that he found it comical or provocative to do so. The projectionist told Austinist that The Human Centipede was “my favorite horror movie within the last few years.” But he also describes the movie in terms that betray a deeper motivation: “It’s something that, when he shows these images and people are disgusted, that’s how I wanna do in my life.”

He’s succeeding, judging from angry and nauseated comments on most of the sites publishing the “Man Gets Unlikely Tattoo” story. That reaction is chiefly split between two types: those being first exposed to the germ, disgusted by the concept and beginning the process of repetition by immediately expressing their distaste in a public forum; and those already familiar, perhaps equally unsettled by the inscribing into permanence of something as fleeting as The Human Centipede’s sway on culture.

The upshot is that all representations of The Human Centipede carry equal weight. Embedded in that tattoo is the memetic nature of the title (for the graphic and title are interchangeable), the sheer stupidity and creativity, and the drive to propagate the virus-here, co-opting its power to perturb the squeamish with a simple permanent line drawing.

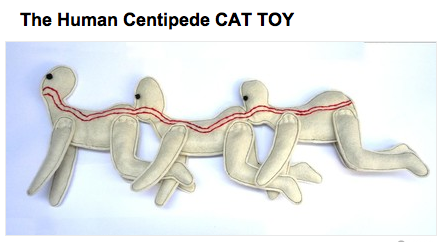

Permanence aside, the descriptive ability of the design holds true of any graphical representation, and others have latched onto the communicative efficiency for (hopefully) comic juxtaposition. Head over to crafter community Etsy.com and you’ll find the exact same diagram as a necklace, a bracelet, a rubber stamp, a magnet, a t-shirt, a sticker, an “art print,” a cat toy. A cat toy? No explanation is given, none needed: it’s simply the compulsion to pass on the virus taking any form at hand for the afflicted individual. For a needleworker, felt and thread. For Richard Dreyfuss, mashed potatoes.

With that compulsion in place, an effective combination of displeasure and easy replication, The Human Centipede became a success as a viral campaign and a cultural meme, if not as a box office product or a film. Besides its presence on MSNBC and nearly every web site with a film critic, it’s made other inroads into popular culture: Flash site Newgrounds hosts the videogame version (a reskinning of arcade classic Centipede, naturally). And what higher tribute than becoming The Human Sexipede, “the most controversial porn parody of all time”?

This is why the title was on everyone’s lips, but the film made a pretty paltry $180 grand in its nine-week run. Its per-screen average in its first multiple-theater week was $2500 a screen, on 17 screens. That’s not bad, but still less than other limited-release options-such non-catchy, non-viral titles as Mid-August Lunch, Valley of the Heart’s Delight, and fifteen others all had better per-screen numbers on fewer than fifty screens. So some people were interested in seeing it, but most were just interested in mentioning it.

If you’re the right combination of clever and lucky, you call your movie The Human Centipede, you get the right internet/festival buzz, you might get a theatrical release and enough press to guarantee you a sequel, or even two. (The first sequel, entitled The Human Centipede: Full Sequence and quadrupling the victim/segment count, is shooting now, the teaser trailer already on the web. Director Tom Six plays it coy when asked about a third part, saying only that he has ideas, but there’s no way he’ll be able to resist the title The Human Millipede.) If that’s your ambition, you can probably always do okay with a movie like this. If your ambition is loftier, you’ll need something more.

In the end, The Human Centipede is a creative concept, but it’s a one-trick pony, with the sort of truth-in-advertising titular transparency that supplies movies like Hot Tub Time Machine with an ironically-earnest elbow-jab. Does Snakes on a Plane have snakes, on a plane? Yeah, it sure does. But does it have anything else?

Matthew Abrams is sorry you had to read about The Human Centipede again.