Music For An Uncommon Era

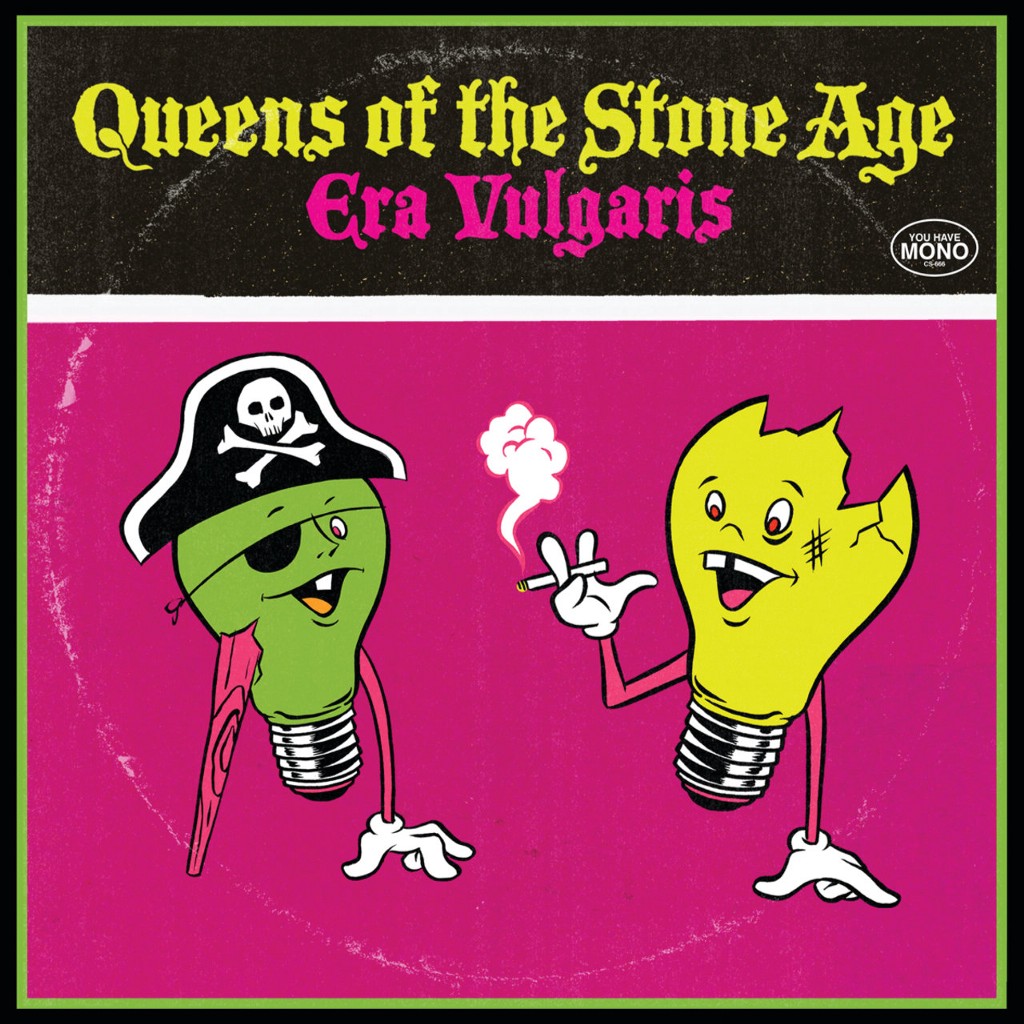

It’s time to admit Queens of the Stone Age’s widely panned ‘Era Vulgaris’ is good.

“I think the two most difficult things to deal with in life are failure and success” — David Lee Roth

For the last few months, Queens of the Stone Age have been teasing a new album like it’s Bret Michaels’s 1986 hair. Given the fractured nature of release dates and schedules these days, it could be months before we hear a note, or it could magically travel through spacetime in a flash, like a nude Terminator Schwarzenegger and be forgotten by the day after tomorrow. For a band whose catalog exhibits eclecticism bordering on schizophrenia, it’s hard to predict what a new album will sound like. Josh Homme is a divisive, bro-y kinda savant, possibly the last rockstar of a bygone era who still has the chutzpah to cause a ripple in an overcrowded ocean of music. Responses to a rare new album from the band can usually be cut right down the middle, 50/50 for and against, but ten years ago, when their fifth album Era Vulgaris came out, it was widely considered by fans and critics to be the band’s worst. Today, it plays like a prescient piece of street art that the masses weren’t ready to understand.

The record begins with enough dead air to make you check if something’s broken, and the jarring, distorted, harmonized ohm that follows is your first clue that something, in fact, is. The drums, both beat and tone, sound like they could have been made in a garage down the street. A distorted synth plunking out whiskey-legged off-beats are the next barrier to entry. In a foretelling of his future collaboration with John Paul Jones, Homme’s guitar enters like a Led Zeppelin after the crash and burn with a bass line that wavers completely out of key and back in again.

If the listener hasn’t already abandoned ship because of the challenging, sub-radio production, a stark departure from their previously slick studio work, the first lyric, an irreverent statement of intent will probably turn them away, “You’ve got a question, please don’t ask it/ Put the lotion in the basket,” the frontman croons, somehow straight-faced. With that, you know that you’re in for a drunk drive through the underside of a decaying city, four or five too many and cocaine of questionable origin in a stall. Loose-lipped, off-color quips that might not pass the next-morning test. If this doesn’t sound like your kinda party, you’re no fun, head home.

Homme apes the ridiculous big rock tradition of the singer calling in the guitar player for a solo by saying, “I sound like this:” and follows it with a series of oddly selected notes and bends, a singular style that came to fruition on this record that he’s continued to cultivate since, as if he’s searching for new notes and scales that are off the instrument, and skipping all the ones we’ve come to expect from decades of phoned-in lead guitar playing. (It’s a style that would reach its apex on his next project, the aforementioned Them Crooked Vultures, whose lone eponymous record is a clinic of musicianship, production and offbeat, fearless songwriting put on by Homme, drummer Dave Grohl and Led Zep bassman John Paul Jones.) From there, the song’s bridge goes on a horror movie bad acid trip of tempo stacking and guitar sliding that’s masturbatory, not in it’s gratuity, but in that it requires an actual jacking-off motion.

“Sick, Sick, Sick,” the lead single from the record begins with imperfect stabs at dissonant chords like an obnoxious alarm clock or bomb raid warning. Drummer Joey Castillo enters with his typical boxy, caveman pounding on boulders with bones style and throughout the song, guitars, bass and synth build to a cacophonous racket that never quite meets in the middle at a single key. The song is, in fact, sick (in the head) and it’s a glorious fuck you to radio and musical norms of auto-tuning, grid-perfect timing, and song structure.

At the time, critics either didn’t know what to do with this oddity, or outright rejected it like it was Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in 1913. People weren’t ready for this level of aural dissonance and flouting of musical standards, sales for Era Vulgaris fell far short of the band’s numbers from previous records and listeners deserted like cats with their ears pointing backwards. The Village Voice said, “with the band sounding listless and drained of ideas, it starts trying anything,” and that the albums’ “stuttering robo-fits are basically energy-drink commercials still ripping off The Matrix.” Basically! Still! The Guardian opined, “something is lacking” on songs it called “oddly slender” and that “lurch distractingly rather than flow.” And Pitchfork? “In attempting to cover too much ground, the band loses focus and direction.” “Everyone sings like they’re scared of their own voices,” and that old timeless classic dis: the “obnoxious bridge on album closer ‘Run Pig Run’ kills any chance it might’ve had for worthy inclusion on a future edition of Guitar Hero.” Indeed, as the subsequent decade has proven, inclusion in a shitty video game is the gold standard metric by which all music is judged.

Fans of the band, who often focus more on set dressing and cast of characters, rather than the albums themselves, also disapproved. They longed for the days of Nick Oliveri, nude but for a bass guitar, who helmed some of Queens’ most embarrassingly bad songs, and was later ousted for violence toward women and concertgoers (he has since admitted that the firing was justified). And, of course, Dave Grohl. Yes, his drumming on Songs For the Deaf is goddamn unassailable, but Dave’s not gonna stop the Dave Grohl Machine to be a sideman, so let’s all deal with it, why don’t we? He’s been replaced by a wild animal and then a master craftsman, what more can Homme do to replace arguably the greatest living rock and roll drummer whose aspirations go far beyond drumming?

Era Vulgaris is practically a case against the band’s past selves. Following a string of radio hits from 2002’s Songs For the Deaf and 2005’s Lullabies to Paralyze that lead the band into bona fide rockstar territory, Queens — with apparent intent — narrowed their fan base. The grimy lo- to mid-fi production and raunchy jokes guaranteed little or no radio play for these songs. Era Vulgaris would be their final record of a major label deal with Interscope records, and its six-years-in-the-making follow-up, 2013’s stellar, cinematic …Like Clockwork would be released through indie legends Matador Records, completing the band’s transition out of the mainstream.

On songs like the robotic ragers “Misfit Love” and “Battery Acid,” the band drips with lurid, half-serious sex appeal and musical prowess. Just try to imagine yourself playing two drum beats at once, like Joey Castillo does here, and here. And is that chorus where Homme declares, “There’s nothing you can say/ You can’t wish me away,” the first and only instance of Stone Temple Pilots nostalgia in history? I think so. “Make It Wit Chu” is a straight up, bluesy goofball sex jam, the joke of which you can only fully understand by realizing that Dean Ween has partial writing cred. The end of the record spins off into a nightmarish, creepshow swirl of twisted psychedelia on “River In the Road” and “Run Pig Run.” It leaves the listener wondering how they got here, returning to the beginning for further listens like a drunk waking up and checking his outgoing messages for incriminating evidence.

The record is a beautifully imperfect monster — a zombie of a former arena rock band. You recognize it and want to invite it in, but you’re afraid it might eat your neck. This is the Pet Sematary version of Queens of the Stone Age that would launch Homme and a cast of legends, unknowns and in-betweens on an artistic journey that keeps unfolding in astonishing and unexpected ways.

Homme almost seemed to know that the record would require a long gestation period. Speaking to Pitchfork prior to the album’s release, he referenced Iggy Pop (whom he’d later work with on the stellar Post Pop Depression) and how it took “35 years for the public to understand the Stooges. I’ve never seen a time release that long before.” It’s been ten years since the release of Era Vulgaris and we can all now acknowledge that everything is falling apart, the empire is crumbling. Homme felt it then and he embraced it, making beautiful, fucked up art out of the the ruins of a dysfunctional relationship with life. Now it’s time for us to let the zombie in. Pour him a drink. He’s dying of thirst.

John Dziuban is no longer a musician. Metal Minutiae is an occasional column on the decline of rock music.