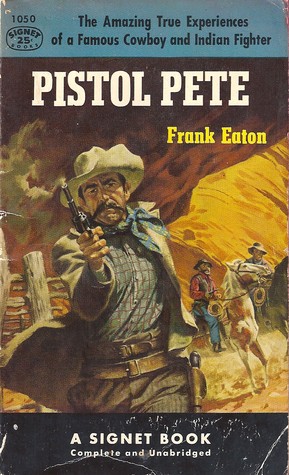

You Ought To Know Frank Eaton

Old-School Show-Off: “Pistol Pete,” Gunslinger and Father-Avenger

Centuries after Hamlet but decades before Inigo Montoya, an American boy set out to avenge the death of his father. His name was Frank Eaton. Some called him Pistol Pete because of his unparalleled trigger finger. He was not a fictional character, but he seemed to know that his story sounded like literature, that there was something trope-like and near-allegorical about his mission. He had a fine sense for the drama of it, and stretched the truth when it served his story. He called his revenge “the great task of my life.”

Across the Atlantic, existentialism, nihilism, and absurdism had already taken root in the minds of European sons, and in their literature, father-son relationships were messy things whose dissolution pointed to man’s alienation from God himself. But frontier narratives like Frank’s never bothered with any of that agonized existential stuff. In Frank’s memoir, good is rewarded, evil is punished, and God smiles down upon him as he gallops across the plains of America, guns smoking in his holsters.

Frank Eaton was born in Hartford, Connecticut on October 26, 1860. His father, also named Frank, was a soft-spoken Civil War veteran who bought a homestead in Osage County, Kansas for his wife and three kids. Both Union and Confederate veterans were settling down in Kansas then, so the atmosphere was tense, bitter, and undercut with violence. Young Frank first witnessed the violence up close at age seven, when his father brought him along to a vigilante meetup that culminated with someone beating a judge to death.

Before long, the violence touched home. When Frank was only eight, a group of six ex-Confederate raiders — the Campsey-Ferber gang — came riding up in the black of night and yelled for Frank Sr. to come to the door, convinced that he had ratted them out to the local sheriff. When little Frank opened the door instead, they burst past him and gunned down his father in sight of the entire family, yelling, “Take that, you goddamn Yankee!”

After his father’s funeral, a family friend took Frank aside.

“My boy,” he croaked, “may an old man’s curse rest upon you if you do not try to avenge your father!”

The next day, the man brought over an old Navy revolver for Frank, and the kid began to practice shooting. Like a Western Hamlet, Frank was forever haunted by the murder of his father, except he spent no time agonizing over what to do next. He knew that he needed to learn to shoot, and shoot well, because the difference between a fast draw and a lightning-fast draw was the difference between life and death. His mission was straightforward, practically Biblical: an eye for an eye, six lives for the irreplaceable life of a father.

From the ages of eight to fifteen, Frank learned to use his gun. There was a purity to his behavior during this time: he rarely shot an animal that he wasn’t planning to eat, he swore he wouldn’t touch a drop of whiskey until he was 40 years old, and he didn’t mess around with girls. (His first kiss was a chaste one, coming from the lips of a devout Catholic girl named Jennie who later gifted him a massive crucifix.) As he grew into a crack shot, his mother remarried, and the family moved to Oklahoma, within the boundaries of the Cherokee Nation. When a teenage Frank stopped by Oklahoma’s Fort Gibson to train with the cavalry there, he found out he was already a better shot than the troops were. “Pistol Pete,” their commanding officer called him, impressed.

He was fifteen when he found out where the first of his father’s killers, Shannon Campsey, was hiding. Shannon had holed up in a creepy little one-room cabin near Oklahoman town of Webbers Falls, also located in the Cherokee Nation. Criminals of all stripes loved to hide out in the Nation — avoiding the US government and filching horses and cattle while they were at it — and so the Cherokee were pleased to hear that this scrappy little teenager had big plans to kill Shannon, who’d been stealing their cattle for years. Frank rode up and spotted the murderer sitting on his porch, a Winchester rifle across his lap. “Hello, Shan, don’t you know me?” called Frank, and at the sound of his voice, Shannon leapt to his feet. “I knew he was fast and a dead shot,” says Frank, “but I had been trained for this since I was eight years old.” Frank emptied two shots into Shannon’s chest before the Winchester ever fired.

Two years later, Frank nabbed the second killer, Doc Ferber, riding up to him and yelling, “I am Frank Eaton and I ought to know you, Doc Ferber, for you are one of the men who killed my father. Fill your hand, you son of a bitch!” The third killer, another Ferber brother, had just been murdered in a poker game (“Somebody else beat me to him!”) and when Frank attended his funeral in an attempt to find the remaining Campseys, a deputy US marshal came up, expressed admiration for Frank’s sharpshooter skills, and offered him a marshal position, even though he was technically too young for the dangerous role. Frank accepted, but insisted on finishing up a few more revenge killings first. Before long, he’d nailed two more Campseys in a single bloody shootout. There was only one killer left.

If Frank’s go-to line — “Fill your hand, you son of a bitch!” — sounds familiar, it’s because that line was made famous by the novelist Charles Portis in his 1968 book True Grit (and in the two subsequent movie versions). Portis borrows liberally from Frank’s life — the unfair death of a father, the killer who joins an unsavory gang, the child-avenger — and though the protagonist of the novel is a 14-year-old girl, she shares many traits with Frank, like an obsessively single-minded purpose and lashings of “frontier virtues.” Sure, Frank kills a lot of people, throws around the word “hell,” and eventually dares to take a swig of whiskey, but he trains for murdering his father’s murderers like some sort of cowboy monk. At the end of his life, he recalls his youth with artless nostalgia, firmly convinced that the wild and bloody life on those plains was, indeed, more virtuous than the “modern” life of the 1950s. He notes, for example, that justice was fairer when it was meted out in the open, man to man, rather than taken into a courtroom.

At the tail end of summer 1881, when Frank was almost 21 years old, he learned that the last Campsey brother, Wyley was out in West Texas. Frank saddled up a horse called Bowlegs and struck off, sleeping under the stars on the way. In Texas, he found that Wyley had skittered off to Albuquerque, and so he rode on. When he galloped into town, the sheriff invited him into the bar for a drink—and who was behind the bar, slinging whiskeys? Wyley, of course. Frank strode in, guns loosened in his holsters, and confronted the killer and his two bodyguards.

“Don’t you remember me, Wyley?” he taunted.

“I never saw you before,” said Wyley.

“Oh yes, you have. It was the night you killed my father! I am Frank Eaton, remember? Fill your hand, you son of a bitch!”

All four of them went for their guns, but Frank, as always, was quickest. He took a bullet in the leg and arm from one of the bodyguards, but all three of his opponents ended up dead. “The great task of my life was finished,” he thought to himself, and rode home.

Though Frank continued to lead an extremely colorful life — more gunfights, a lot of wrangling cattle, and his first taste of whiskey — he was on his way to settling down. He bought a claim in Oklahoma in 1889 and married a girl named Orpha under a big oak tree just before she turned 16. They had two girls, and for seven years, he “knew what heaven must be like.” Then Orpha took sick and died, but eventually Frank met his second wife Anna, had eight more children, put down his guns (for the most part), and took up the fiddle. Finally, he opened up a blacksmith shop in the town of Perkins, Oklahoma.

By the time a 92-year-old (!) Frank sat down to write his memoirs in 1952, the frontier was no more. It had been officially “closed” in 1890. Frank was, distinctly, a product of another time — the child of an America that had vanished.

A decade after Frank’s memoir was published, philosopher Maurice Friedman wrote a book called Problematic Rebel: An Image of Modern Man, which described precisely who Frank was not. Modern Man, after all, is characterized by fragmentation and alienation — often, a fragmentation from his own father. “The inner division which results from the alienation between fathers and sons is as much a commentary on the absence of a modern image of man as on the breakdown of the specific father-son relationship,” noted Friedman. “At the heart of this breakdown, in fact, is the inability of the father to give his son a direction-giving image of meaningful and authentic human existence.” This alienation from the father leads to an alienation from God and an alienation from the self, resulting in the splintered, anguished heroes of Sartre and Dostoevsky and Camus. Even Hamlet fits under this “modern” paradox, lost in a world where the only direction he gets from his father is the howling of a ghost.

But that’s not Frank. His father, by dying in front of his son in a puddle of blood, gave Frank precisely what Modern Man never got: a “direction-giving image of meaningful and authentic human existence.” The death of the father gave his son purpose, a sense of right and wrong, a place in the moral order of the chaotic frontier, a reason to move through the West with confidence. Dying in front of his son was a great gift. And it marked him as a product of a past that — like the frontier — is closed forever. Revenge stories like Frank’s are told, now, mostly as fiction.