A Frustrated Former Percussionist Revisits Stravinsky's 'Pétrouchka'

Classical Music Hour with Fran

I’ll be honest with you and say that it’s now been almost four years since I played with a symphony orchestra of any kind. For almost all of college, I played with the community philharmonic — I went to a small liberal arts school that didn’t have enough students to justify its own orchestra — until my very last quarter of school, in which I had a rare conflicting class and didn’t get to play the final concert of my senior year. This was annoying at the time, given the seniors in the philharmonic were usually acknowledged at the final spring concert with, like, I don’t know, a rose or something and a special round of applause. I wanted that! I had toiled through a lot, especially — especially — what became final the winter concert of my senior year in which we played… Pétrouchka.

This ballet by Igor Stravinsky was one of the single most difficult pieces I ever played. I was not a music major and I never took any private lessons in college. The percussion in Pétrouchka was not only prominent but hard. This wasn’t some typical timpani here or timpani there; this was snare drum and xylophone (!!! is this whole column a vanity project to write about pieces that have good xylophone parts? WHO’S TO SAY) and triangle. The whole shebang, and it nearly killed me. For three months, I ate, drank, and slept Pétrouchka. That’s not a joke for the most part: any time I walked around campus, I listened to it. I drove to it. I played it while I did work. I had to ground it into the very fiber of my being in order to learn it, then promptly forgot it within the weeks following the concert. Then, several years later, with a cold breeze from — I don’t know where breezes come from, the north? — I started listening to it again.

Stravinsky has made a brief cameo in this column before, in reference to Saint-Saëns walking out of The Rite Of Spring, one of Stravinsky’s most famous pieces. Stravinsky was a Russian composer, working predominantly in the first half of the 20th century. Besides The Rite Of Spring, it’s possible you know Firebird, his other most famous ballet. I wish I had good gossip for you about Stravinsky, really, but he’s a composer whose work is so deeply complex to me that I can barely emerge from the pieces themselves to dig up if he was weird or bad in some way. I did find out he got typhoid from a bad oyster once. Be careful out there, folks!!

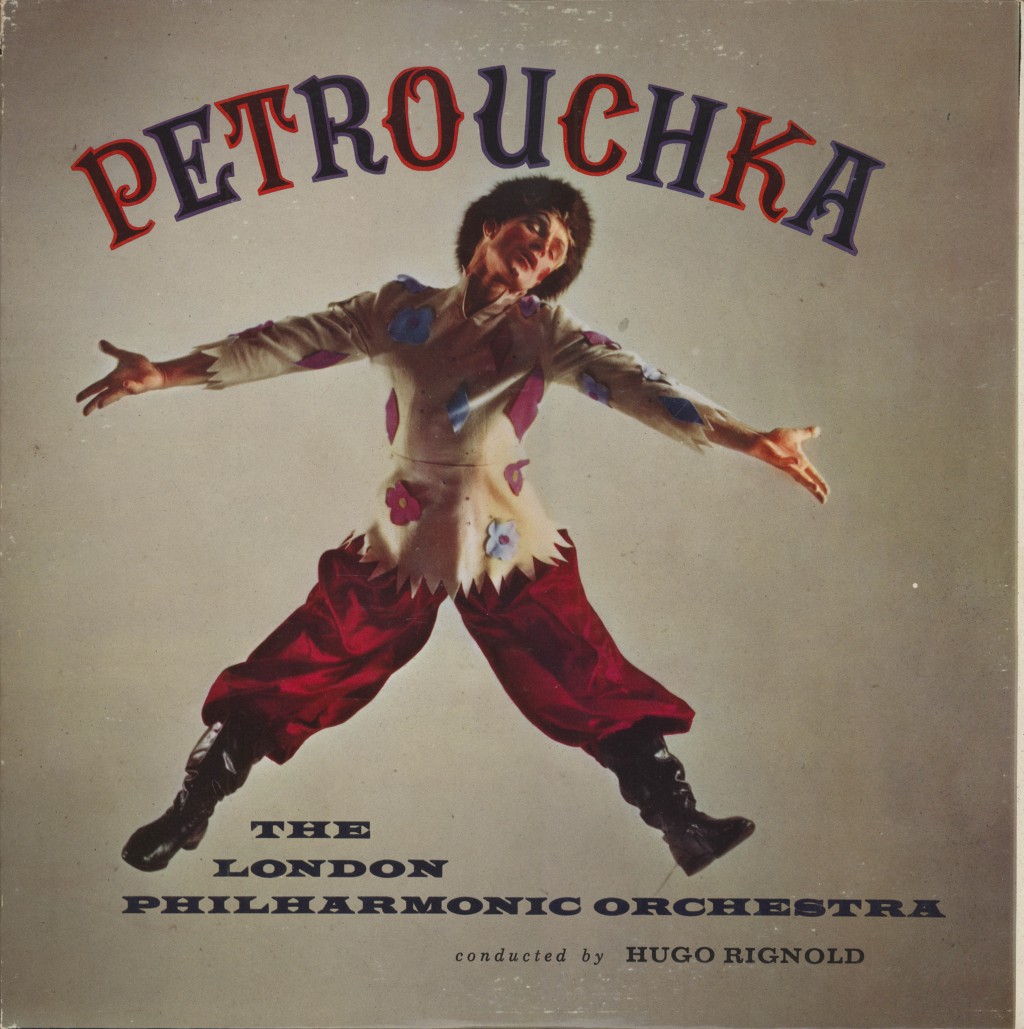

So anyway, Pétrouchka is a ballet. It’s named for its title character, Pétrouchka, who you’re maybe like, “who the — ” but you’re likely familiar with. Pétrouchka is the Russian equivalent of Punch, as in Punch and Judy, as in the bad puppet couple. Wikipedia describes Pétrouchka’s main activities as: “He enforces moral justice with a slap stick, speaks in a high-pitched, squeaky voice, and argues with the devil.” Hm, same. The plot of Pétrouchka is, uhh, fine. It’s fine. It’s a love triangle between three puppets who have been brought to life at a street festival: Pétrouchka, a ballerina, and a Moor. That’s really it. I would love to tell you it’s more engaging than that, but hey, these Russians sure do love when puppets come to life.

You’ll start listening to to Pétrouchka (I recommend the 1962 New York Philharmonic version conducted by, you guessed it, Bernstein), and you’ll notice that it even sounds difficult. The Nutcracker ballet, for example, although written by an entirely different composer in an entirely different century, is a much more rhythmic ballet. It’s easy to find an anchor in it, a constant pulsing for dancers to grasp onto. Pétrouchka is more hectic and chaotic. Its opening minute of its first tableau, entitled “The Shrove-tide Fair” (which is the name of the Russian festival Pétrouchka mainly takes place during), is a flurry of strings and fanfare. As I previously mentioned, it’s got a whole array of percussion, but it’s also got quite a lot of other interesting instruments. Piano, for example, plays a prominent role. So does the harp! How do you even play harp? The harp is impossible. I think half the reason I struggled to learn my Pétrouchka parts in college was because I spent most of rehearsal watching the harpist.

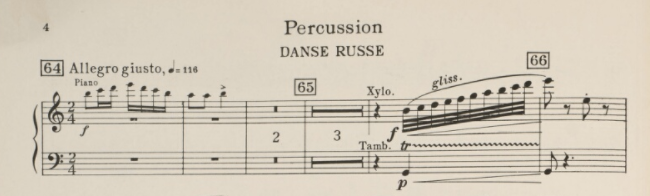

Where Pétrouchka really gets going, by which I mostly mean, where I start to have PTSD-style flashbacks of playing xylophone, is the third part of the first tableau, entitled “Russian Dance.” Here’s the opening of the xylophone part, where you can see a triumphant glissando.

What’s a glissando, you might be asking? It’s when the xylophonist basically hits a note and then drags the mallet up the keyboard. It rules, obviously, because I think at their most tender and pure selves, percussionists often just like to hit notes.

But then the piece really picks up. There’s a piano solo. It’s moving, it’s dance-y, let’s not forget, puppets — of all things! — are coming to life. And the xylophone got… impossible… You can hear it creeping through the final thirty seconds of the “Russian Dance” — audible for, say, the whole orchestra to hear, especially if you, a 21-year-old part-time percussionist fuck it up.

You’d think from this description alone that this whole ballet is one long and frustrating xylophone part. It really isn’t — I’m profoundly exaggerating, mainly because there’s just so much going on in Petrouchka. Take later on, “The Dance Of The Ballerina,” which is a duet between a snare drum and a trumpet. It’s odd and wonderful to have a brass instrument signify the part of the ballerina, a character typically represented by a flute or a clarinet. I love it. It’s oddly militaristic and powerful for a fanfare for the central female character. What I would give to have this little minute-long melody play anytime I come to work in the morning.

This leads right into a odd and gorgeous little waltz starting with a bassoon solo. A bassoon solo! It’s whimsical and almost wistful, nearly immediately covered up by both the flute and the clarinet. What I’m trying to say is mainly: Petrouchka is weird. It doesn’t follow any conventional structures, and unlike symphonies and concertos, it’s tougher to navigate. Looking back on this piece and listening to it after a couple of years, I mainly just find myself marveling at it. It’s strange! For someone who used to have the whole thing memorized, I found myself surprised by it again and again. It’s colorful and absurd and really gorgeous in parts (especially for how generally uninteresting its story is). It’s possible you’ll listen to it and think things like, “Wait, the clarinet’s coming in here?” or, “How come there’s trombone happening here?” or, “Wow, this is a truly demanding xylophone part, and kudos to any college student who played it.” It’ll challenge you, but trust me, you’ll get through it.

Fran Hoepfner is a writer from Chicago. You can find a corresponding playlist for all of the pieces discussed in this column here.