No Country For Its People

A short history of modern Iraq’s ethnic minorities

“…an Iraqi people does not yet exist; what we have is throngs of human beings lacking any national consciousness of sense of unity, immersed in religious superstition and traditions, receptive to evil, inclined towards anarchy and always prepared to rise up against any government whatsoever. I have begun with the army because I consider it to be the backbone for the creation of the nation.” — King Faisal I, 1932

Iraqi society has never been more disjointed than it is today. The long decade since the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 has pulverized relations between the country’s communities and decimated its smaller populations. The emergence of ISIS led to demographic and territorial disfigurations so deep that even attempts to reverse them could move the country further away from any sort of meaningful coherence. The dream of an ethnically plural Iraqi state is now an even more remote prospect than it was upon the country’s foundation as an independent kingdom in 1932.

From the outset of independence, the Iraqi Army swiftly set about straightening Iraq’s backbone, roving across the new borders of the state with demonstrations of force. The new country’s Sunni-led government crushed uprisings led by Kurds, Yezidis, and Shi’a tribes. In 1933, three thousand Assyrians were massacred in a series of rampages as the nascent Iraqi army slaughtered their way through villages in the north. The military quickly emerged as the only institution capable of cohering the country, and violence became the principal ideal of Iraqi governance.

The belief that Iraq was an Arab state — and that its citizens should either become Arab or be punished for not being so — became the guiding principle of social control. Groups within Iraq but not loyal to its rulers have long been construed as fifth columns: the Shi’a, for their allegiances to Iran; the Assyrians, for the assertion of their indigenous ethnicity, their ties to the British, and their ambitions for autonomy; the Kurds, for placing their own interests above those of the state; and the Jews, for participating in the international Zionist conspiracy.

The militarization of Iraqi politics led to an extensive history of coups and counter-coups; Saddam Hussein took over in 1979 after a few more. Saddam’s Ba’ath regime hailed the resurgence and unity of a superior ancient race (the Arabs); pursued the righting of wrongs suffered under foreign influence (e.g., the annexation of Kuwait); exhibited ruthless disdain for all other forms of political organization, especially communism; and was profoundly anti-Semitic. Non-Arabs were expelled from ethnically mixed areas, largely in the north, their property seized and destroyed, and replaced with Arabs. The Kurds were eventually targeted for annihilation.

Following the toppling of the Ba’ath regime in 2003, western state-crafters largely turned to exiles to run the country. Many of these men had been banished from Iraq by Saddam when they were young for opposing his rule, and spent the subsequent decades in states of paranoia and intellectual stagnancy. The scene was set for them to unleash their blinkered partisanship and aggrieved sense of righteous destiny into the new Iraq.

The leaders of the Iraqi Governing Council, the transitional authority from 2003–4, began de-Ba’athification, which saw prominent officials and thousands of rank-and-file employees loyal to Saddam removed from office and barred from participation in the new Iraq. Under the auspices of Paul Bremer, the American architect of the occupation, the core of the state was gutted. The returning exiles atomized the Sunni presence in Iraq — in 1922, a year after Iraq was created as a League of Nations mandate, not a single Shi’a was in its provincial government; by 2006, as ethnic violence tore Baghdad apart, only one out of fifty-one members of its provincial council was Sunni.

One of the central tasks of Nouri al-Maliki, Iraq’s Shi’a Prime Minister from 2006 to 2014, was to rebuild a national army. But he refused to integrate the Sahwa militia — a popular Sunni force that had subdued al Qaeda in Iraq — fearing a loss of influence over the security forces, and filled the army’s ranks with Shi’a loyal to him. Maliki had Sunni leaders imprisoned and executed, accusing them of perfidy and sundry crimes, and invoking the de-Ba’athification laws, which could be applied in a highly elastic manner to marginalize or persecute nearly anyone.

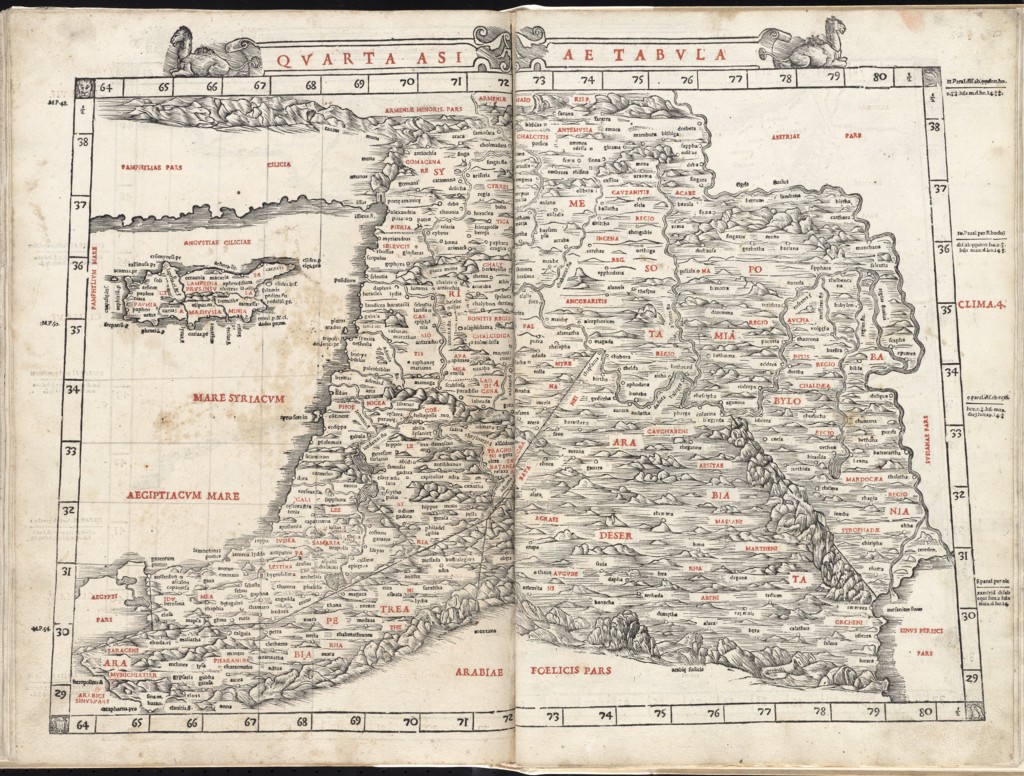

Today, preachers foment vicious sectarianism on the streets of Baghdad, directing the alienation and suffering of Iraqis towards perpetual righteous fury. Sunni jihadist groups target the Shi’a population and mosques with waves of car and suicide bombings. Shi’a symbols — images of Ali, the al-Sadr family — are publicly displayed as if those of the state, and Shi’a nasheed — jihad hymns — blare out of government buses. The Mahdi Army, a death squad loyal to the Shi’a demagogue, Muqtada al-Sadr, set about ridding entire Baghdad neighborhoods of Sunnis. There are several maps depicting this demographic cleaving — one includes Christian neighborhoods — but the most important ones show the crucial decline of mixed neighborhoods.

Iraqi leaders have woven the country’s narratives around their hatred for one another. Their tussle for control over communities and the country has come at the expense of both. For Iraq’s smaller peoples — such as Mandaeans, black Iraqis, Assyrians, and Yezidis — this brutalization has taken a disproportionate toll.

The Mandaeans practice an ancient gnostic religion. Their name comes from the Aramaic for “knowledge.” (They are also known as Sabians — the root of which, sba, is Syriac for plunge or bathe — in reference to the central place of baptism in their religious culture). Submersion into water is not merely a sacrament, as in Christianity, but a rite that accompanies the majority of Mandaean rituals, including marriage and preparation for death. Ancient inhabitants of southern Mesopotamia, they have largely been confined to the marshes, channels, and deltas of Khuzestan and Basrah with successive persecutions.

Mandaeans have their own language and scripture, which is close to the dialect of the Babylonian Talmud. Their alphabet adds two letters to the twenty-two usually found in Aramaic. Alap (written with a circular glyph) begins and concludes their alphabet, signaling the wholeness of the twenty-four hours and the perfection and completeness of the universe. They were silver and goldsmiths, and in the twentieth century, many moved to Baghdad and became doctors and pharmacists.

There were sixty to seventy thousand Mandaeans on the eve of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003; following waves of kidnapping, rape and murder, only a few thousand remain. Knowledge of their faith and written language is confined to their priesthood, and the clergy is dwindling. Their diaspora threatens the continuity of their traditions: Sabian architecture — manda — must be built on flowing (“living”) water, which serves as their sacred space. This is often a problem in the various major western cities in which Mandaeans seek asylum, and where water is too dirty to be used for rituals. For Mandaeans, water is a symbol of God: the source of wisdom, birth and renewal in the universe. Their communal severance from it is a symbol of their disappearance.

Iraq has a significant population of black African descent, concentrated mainly around Basra — a predominantly Shi’a province that produces significant amounts of Iraq’s oil, near the ports settled in waves across centuries of slave trading. Many still practice aspects of the heritage they brought with them, from healing and mourning rituals to spirit summoning and African dances and instruments. Like African-American slaves, they built cities, staffed the homes of the rich, and worked on plantations and farms. There is even a parallel controversy over the word Arab Iraqis use to term them — Abd, slave or servant — the modern, casual deployment of which speaks to an ongoing legacy of racial inferiority. No black Iraqi has ever attained a government position; most work menial jobs, washing cars or providing local private security for businesses.

Black Iraqis do not have their own ethnic quota in Parliament, unlike almost all other ethnic and religious groups in Iraq. Come election time, Sunni and Shi’a parties lure them with bribes and gifts in exchange for oaths swearing allegiance to Allah. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement and further emboldened by the election of Barack Obama, black Iraqi community leaders tried to mobilize their communities. Jalal Diyab, founder of the Free Iraqi Movement, lobbied to get black Iraqis on provincial councils — and most significantly, he sought to have blacks represented as a discrete ethnic block in Parliament, where they have never had a representative. He was shot dead on April 26, 2013. No investigation into his murder took place, and the other candidates of the Free Iraqi Movement withdrew from the local council elections.

Assyrians trace their heritage to the ancient Assyrian civilization, which also encompassed the state of Babylonia in today’s central and southern Iraq. They became some of the earliest Christians, and navigated life under the Persian and Islamic Arab Empires. Following the devastating Mongol sweep across Asia in the thirteenth century, the Assyrians were largely confined to the mountains of northern Mesopotamia and the plains that stretched out from them. When their bid for autonomy failed, the Assyrians of the Hakkâri mountains (in today’s south-east Turkey) were expelled from their highland redoubts. Along with the Kurdish tribes they conscripted, Turkish nationalists attempting to create an ethno-religiously pure Republic deported or killed every Christian they could find between 1914 and 1923, and murdered around three hundred thousand Assyrians.

The surviving Assyrians marched, starved and ravaged, towards uncertain futures across the region and beyond. Most ended up concentrated within Iraq, scattered across refugee camps and exposed to further depredation. Iraq celebrated its independence by massacring three thousand Assyrians in and around the village of Simele in 1933, an exhibition of how the state planned to treat the potentially disloyal. Crowds in Baghdad greeted the returning army by garlanding them with flowers and rose water.

But the violence of the early decades of the century left a permanent legacy. The Patriarch of the Chaldean Church, a Catholic offshoot of the Church of the East, and a bishop of the Syriac Orthodox Church in Iraq wrote to King Faisal, probably under duress, congratulating him on the “peace” yielded by the massacre. The Church of the East Patriarch, Mar Shimun, was exiled from Iraq in 1933.

Saddam let the Assyrians be Christians as long as they exchanged everything else about themselves for the privilege of worship. Assyrian civil organizations, media outlets, and clubs and societies were outlawed by the mid-seventies. The modern Assyrian language — the morphology of which is partly rooted in the Akkadian language of the ancient Assyrians — was restricted to the home. Ancient Assyrian figures were depicted as early Iraqi Arabs, undermining Assyrian claims to an indigenous, non-Arab ethnicity.

Catholic schools taught their pupils in Arabic rather than Assyrian; one of the men closest to Saddam was a Chaldean Catholic who Arabized his name from Mikhail Yuhanna to Tariq Aziz. When Saddam was still feted by America, he was handed the key to the city of Detroit after donating two hundred and fifty thousand dollars to a Chaldean Church (whose reverend had publicly congratulated the dictator on his ascent to power).

Jockeying for a piece of influence was a mainstay of life under Arabist totalitarianism — with the lid of tyranny lifted, preachers, bishops and imams pulled apart the strains of ethnicities and congregations. In 2003, in the run-up to the U.S. invasion, the influential Chaldean bishop Sarhad Jammo wrote a letter to Paul Bremer describing the grouping of Chaldeans with Assyrians — in fact ethnically indistinguishable save for sect — as “an injustice against our people” and demanded that they be recognized as a separate ethnic group, despite previous claims to the contrary.

Since 2003, Assyrians have been the targeted victims of the whole spectrum of atrocity. More than seventy churches across Iraq have been attacked or destroyed. Entire neighborhoods have been emptied of their residents following episodes of rape, murder, and intimidation deliberately fashioned to purge Iraq of Christianity. A pre-2003 population of around 1.2 million mainly ethnically Assyrian Christians in Iraq has dropped to four hundred thousand.

All of the poisonous movements in Iraqi politics conspired in June of 2014, when Mosul — Iraq’s second city — fell to ISIS. Mosul, a largely Sunni city that was historically a hub of mercantile comingling, had been plagued by the Sunni insurgency since the collapse of central authority in Iraq in 2003. Racketeers funded jihadi activity by theft and extortion; dozens of teachers, professors, and other educated people were killed or expelled; clergy were abducted and executed. Suicide bombers targeted administrative and government institutions. Three weeks after the capture of Mosul, the groundwork was laid for the declaration of an Islamic Caliphate.

Following the full withdrawal of US troops from Iraq in 2011, the expression of Baghdad’s insecurities towards Sunnis intensified. On paper, the Iraqi army in Mosul outnumbered the invading ISIS fighters by at least ten to one. But the largely Shi’a government forces were deeply resented by their charges, who perceived them as occupiers loyal to a remote and repressive state dedicated to sectarian persecution and marginalization.

The army in and around Mosul had extraordinary organizational and operational problems — poor training, dilapidated structures, failures of payment, “ghost” divisions, and corruption so endemic that soldiers would often bribe their superiors to abdicate duty. So what, and who, was the army fighting for? For Iraq’s political class and the Army officials tied to it, Mosul was not a city worth risking lives for; it fell with barely a shot fired. Souvenirs of the Iraq that its protectors had shed — badges, flags, uniforms — littered the ground. The jihadists treated themselves to a harvest of their desertion, reaping the Humvees, ordnance, tanks, weapons and bullets that America had endowed Iraq with, using them to carve their way into the state the machinery was purchased to defend.

A few weeks into the Islamic State’s occupation of Mosul, it tagged Christian property with “N” for Nassarah, the Quranic term for Christian, and Property of the Islamic State. Christians were told by decree on Friday, June 18th, that they had a day to decide whether to convert to Islam, live as Dhimmi, a subjugated rank afforded to some non-Muslims under a Caliphate, or flee. All but those who were too old or infirm to leave fled. They were robbed of all they owned, down to identification papers, pension books, and babies’ earrings. All forty-five Christian establishments in Mosul were closed, destroyed, or converted into an apparatus of the Islamic State.

The other historically Assyrian towns of the Nineveh Plains were all emptied of their hundred and fifty thousand inhabitants as militants sped along unobstructed. Thousands of Syriac manuscripts were burnt, and testaments to the Syriac Christian heritage were desecrated. The fourth-century Mor Behram monastery, built on the tomb of the children of the last pagan Assyrian king, was blown up in March. The Islamic State has also waged a campaign of destruction against the ancient material culture and heritage of northern Iraq, laying waste to the Assyrian cities of Nimrud, Dar-Sharrukin and the Seleucid city of Hatra. Just as they did a century ago, deracinated Assyrians roam Mesopotamia, seeking succor. Tens of thousands live on roadsides or in makeshift accommodations in the Kurdish-controlled cities of Arbil and Dohuk.

The Yezidis, concentrated in northern Iraq, adhere to an ancient Mesopotamian religion, influenced by Zoroastrianism, with Mithraic, Sufi, and Abrahamic elements, as well as sui generis teachings, superstitions, and legends. They believe that Xwede, the eternal God, created the universe, but then handed dominion over worldly affairs to a heptad of angels. Malek Tawus — an angel in the form of a peacock — is the most important: the mediator between humanity and Xwede. Their profound attachment to nature, a legacy of the original Mesopotamian faiths, extends to kissing trees, praying in the direction of the sun, and reverence for snakes and birds.

Yezidis do not prize a scripture — they have transmitted their communal mythologies, fused with memories of their persecutions, orally. (They probably only began to collate their fragments in response to the interest of nineteenth-century orientalists, although some Yezidis state that their original scriptures and language were destroyed by Muslims.) Their faith lives through memory, speech, and song, embodied in sanctuaries, shrines, and complex, insular modes of social organization. They accept no conversions, believing that they alone are descendants of Adam but not Eve. They are divided into castes endogamous within themselves. There are large Yezidi communities ins Ain Sifni and the Shekhan district of Nineveh, where they live alongside Assyrians, as well as in the Sinjar region in the northwest. The ribbed, fluted domes of their distinctive religious architecture punctuate the landscape.

Following the outbreak of ISIS across Nineveh, the Yezidis have been subjected to a campaign of genocide. They are not even recognized as ahl al-kitab, “people of the book” — those who follow scriptures deemed holy in Islam — a category that should extend to Christians, Jews, and Mandaeans. A fraudulent old calumny that construes Yezidis as devil worshippers has provided the religious justification for the Islamic State’s attempt to terminate their existence.

In the early hours of August 3rd, ISIS militants invaded Sinjar and surrounding villages, forcing tens of thousands of Yezidis to flee, mainly into the mountains, where they began to die from thirst, hunger, and heat exhaustion. Yezidi males old enough to have armpit hair were rounded up and executed or buried alive. Boys with hairless underarms were abducted, to be groomed into jihad. Young women and girls were abducted and sold into sexual slavery. Matthew Barber, a scholar of the Yezidi plight, has the names of at least forty-eight hundred girls involved in such abductions and around the same number of men killed. Some early eyewitness accounts of the enslavement of girls emerged on social media (along with many denials), but an article in the official Islamic State magazine Dabiq attempted to present a coherent Islamic explanation: In accordance with Sharia, the “polytheists” were rightfully distributed among the fighters “to help men avoid the sin of adultery.”

The only ground forces that provided a safe passage for beleaguered Yezidis around Sinjar were the Kurdish YPG militia of Syria. As the Iraqi army withdrew from the north, Kurdish militias quickly filled the vacuum. For a while, ISIS and the Kurds seemed to have an understanding: You take yours from Iraq, and we’ll take ours.

When ISIS began to advance on Assyrian and Yezidi towns — which had been occupied since 2003 by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), who had disarmed the inhabitants — the Kurdish militias known as peshmerga (“those who confront death”) withdrew and fled back to areas securely held by the KRG. This betrayal continues to provoke a profound feeling of mistrust from Yezidis and Assyrians alike. The collaboration of some of their Arab and Kurdish Sunni neighbors with the Islamic State has compounded the sense among exiled Assyrians and Yezidis that they would find it very hard to go home, even if their towns were liberated.

The KDP (Kurdistan Democratic Party) — the dominant, tribally organized party within the KRG — has attempted to patronize the Yezidis into identifying as Kurds. In KDP propaganda, Yezidis are depicted as “original Kurds.” Yezidis act as a kind of living museum for the Kurdistan project, which has sought to implant deeper civilizational roots and narratives to render Kurdish territorial and national claims more robust. In exchange for KDP votes, the peshmerga promised to protect Yezidis, pressuring them to stay put until hours before the ISIS incursion — conveying no sense of imminent danger or of their own potential flight.

The Yezidis count seventy-two persecutions in their history: this latest could permanently disfigure their culture. There is little in the way of a coherent strategic understanding of how self-reliance could meaningfully sustain the Yezidi people.

ISIS has been deemed an unprecedented evil, but it represents the consolidation of disparate strains of violence and religious totalitarianism hatched across the region. Consolidation into a Caliphate has magnified and systematized the horror. It has certainly put into relief the abject failures of national organization in the Middle East. The lucrative ISIS trade in artifacts pilfered from archaeological sites consumes material history to fund the illusory manifestation of the original Islamic khilafah (Caliphate) and set in motion its eschatology. History becomes the very fuel by which it is burned.

Many of the more prominent former members of the Ba’ath party have put their skills and expertise, if not their ideology, to work in the formation and operation of the Islamic State. Their genocidal policy towards Shi’a Arabs is savagely regressive and steeped in sectarian mania, but is also a gamble of allegiance with echoes of the ethnic cleansing that created nation-states like Turkey and Serbia.

The flag of the Islamic State still flies over Mosul and much of Nineveh, and it tells its own visual story: primitive and stark, the warmly rounded letters — inviting in their almost dumbly handwritten thickness — spelling out the beginning of the shahada, the central Islamic creed. The circle beneath them, intended to represent the original seal of Muhammad, suggests a planet engulfed in the end of everything that came before him. A call to a pure beginning, their approach to statecraft is both shockingly regressive and consciously transgressive in relation to both modern Arab states and Islamist organizations.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi can be seen brushing his teeth with a miswak before his Mosul sermon, an affectation designed to hark back to the time of Mohammad — and yet his organization publishes a glossy four-hundred-page report annually, complete with infographics detailing the stylistic variety of their murders. The foreign fighters of ISIS have made a show of burning passports. Alongside propaganda and pageantry, ISIS moved with great speed in providing state functions — police, welfare, retirement homes, food distribution, law courts, street cleaning, electrical repairs — after the Caliphate was declared, making good on the pledge of a comprehensive Islamic entity while gains were still being made and the adrenaline of a prophetic vision was coursing.

Since the convulsions of summer 2014, the two most significant territories taken back from ISIS in Iraq have been Sinjar and Ramadi. Sinjar was re-taken in November of last year by Yezidi and Kurdish forces just as easily as it was abandoned by the peshmerga in the first place. The operation took two days, having been stalled for over a year, over questions of how to coordinate and divide both the operation and the spoils of it. The destroyed city is now occupied by a patchwork of competing militias and political interests. Mass graves of Yezidis slaughtered by the Islamic State are still being unearthed.

As for Ramadi, (strategically more important for the Iraqi government as it connects Baghdad to Syria and Jordan), some 80% of the city has been destroyed in the process of Iraqi security forces retaking it from ISIS, on top of damage and displacement sustained during a prior tussle for control in early 2014. While ISIS has been largely dislodged from the city, they will continue to pose a constant threat of infiltration and terrorism, impeding the repopulation and restoration of the city. Similar problems are likely to befall Fallujah, which the Iraqi army and affiliated militias are currently attempting to re-take from ISIS.

When it comes to Iraq, there is no status quo ante bellum. ISIS emerged out of the same fragmented and lawless Iraq that is now trying to combat it. The same failures that led to the rise of the Islamic State are plaguing attempts to defeat and supplant it. The heavily politicized nature of the Iraqi army, as well as the opportunistic presence of largely Shi’a militias beyond government command in anti-ISIS operations, is one deep problem. What will come after liberation is the next. It is almost inconceivable that the Iraqi government, riven across all lines and utterly beset by partisanship, corruption, greed and incompetence, can create a lasting sense of allegiance across its citizenry. Each side in Iraq is striving to position itself to emerge stronger after ISIS — but only to reap the greater spoils of their defeat.

At a rally calling for the protection of Iraqi minorities in London in September 2014, Iraq’s spurned inhabitants huddled to yell at the country that authored it. Chants modulated to include as many minority communities as had members present. As Mandaeans, Yezidis, Assyrians and others joined the crowd, they instructed those leading the chants to add their names to the roll call of peoples that needing saving. At the edge of the rally, just within earshot, a small group of Shi’a Arabs — a family of three and their friend — gathered around a bench in disappointment. The mother complained that the focus was on Christians. “What you’re saying happened to you has happened to us, too.”

These dispersed ambassadors of their former country were like strange relatives meeting at the funeral of a distant relative. Everyone was weighing their tears. They mourned not Iraq, but what it had taken from them.