Post Aesthetics and the memetic Marxists

What happens when a Facebook meme group takes itself seriously?

The Marxist purge began about two weeks ago. First, there was the coup: twenty elected leaders were overthrown and replaced by a single, all-powerful administrator. Thousands were eliminated at the mercy of an unstoppable automated script. The population dropped from 45,000 to 10,000 in a matter of days. They banned all comments. Then, they came for the memes.

Post Aesthetics was a secret Facebook meme group populated mostly by students at elite colleges. In the cultural universe of Weird Facebook, it was a heavy hitter — a little danker than Bernie Sanders’ Dank Meme Stash, and a little cooler than Cool Freaks. It made some things that attracted mainstream attention, like a full-length Jeb!-themed Hamilton parody and a debate over the identity politics behind “dat boi.”

At its height, members of Post Aesthetics submitted hundreds of memes per hour to the group. These ranged from your typical text-over-image macros to absurdist personal narratives and screenshots of social media oddities. A small army of moderators, or “mods,” sorted through the deluge of content to remove offensive posts and quell arguments in the comments. The mods also served as gatekeepers: they had to approve each potential joiner and could ban any offender.

Soon after its founding in late 2014, Post Aesthetics grew exponentially. When a mod added me to the group last summer, I knew virtually none of the other members. By winter, almost half of my Facebook friends had joined, drawing both from my over-connected college in New York City and my hometown in rural Maine. Content from the group soon blanketed my social media feeds, and group texts with college friends turned into strings of Post Aesthetics memes. It became a real online community: that type of organic, unique, shareable place that every media company and social app aspires to create.

Like the memes it contained, though, as Post Aesthetics snowballed in popularity, it spun off innumerable derivatives. Members who ended up on the wrong side of the mods went and founded other groups. Post Post Aesthetics gave way to Post Post Post Aesthetics Aesthetics Aesthetics. Shitpost Aesthetics celebrated the sort of low-effort, low-quality content that would have been bannable in P.A. proper. Aesthetic Content Holdings, LLC brought corporate structure to meme production. East Coast Aesthetics took it regional. And so on.

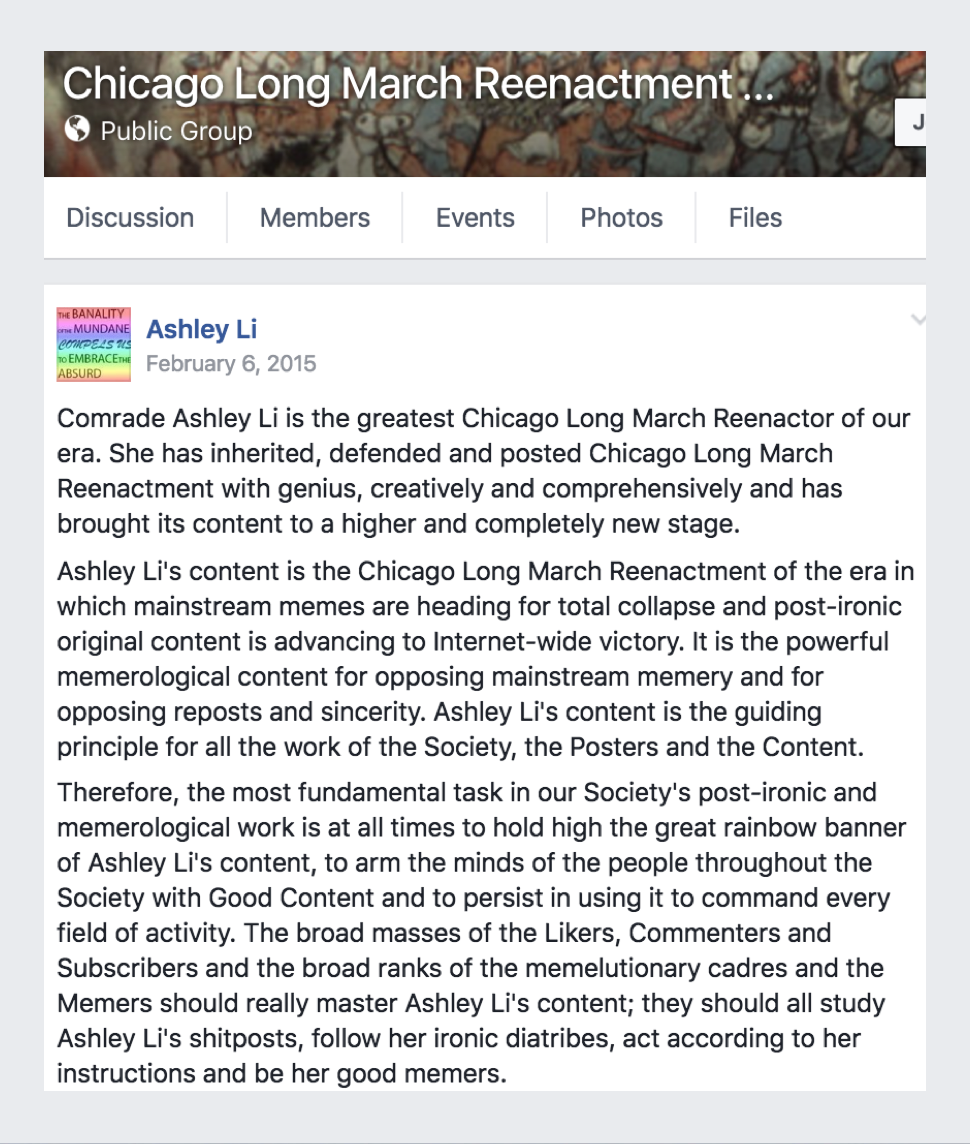

One splinter group was different: the Chicago Long March Reenactment Society. Founded in January 2015 by another UChicago student, Ashley Li, this group didn’t host memes at all. Instead, members wrote essays about internet culture, all couched in a sort of quasi-ironic hyper-academic neo-Marxism. The first three posts in the group were a Chinese-language summary of the actual historical Long March, a piece entitled “Semiotics/Influence of Revolution, Part 1: Brogrammers of Silicon Valley” and this:

Even though the Chicago Long March Reenactment Society was much smaller than Post Aesthetics — a few hundred members versus tens of thousands — in the world of Weird Facebook, it had some real influence. Its leaders, including Li, were some of the earliest active participants in the original group. But as Post Aesthetics grew, new moderators had taken over, and old ones were pushed out.

Li admitted that the Chicago Long March Reenactment Society began like the other niche groups in exile from Post Aesthetics. At its creation, the group was intended to be ironic: “CLMRS was really just a shitposting group that edited Marxist literature with meme-related terms,” Li said. But it slowly got serious. The Long Marchers abandoned the Chinese Communist cover; posts started citing real cultural theorists like Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and György Lukács.

“CLMRS only turned explicitly Marxist,” Li said, “as I realized that the circlejerk [of Post Aesthetics] could be reformulated along the lines of that theory.” A series of essays published in the group later in 2015 proposed a complete “theory of counterculture” and a “scientific analysis of contemporary irony.” The transition of CLMRS from communistic copypasta to cultural criticism was complete. And so emerged the Marxist faction for the oncoming Weird Facebook civil war.

Meanwhile, back in Post Aesthetics, the group’s massive growth had made things chaotic. Thousands of meme creators were competing for group-wide attention, seeking the critical mass of likes and comments necessary for Facebook’s algorithms to push posts to the top of members’ newsfeeds. In search of content, some copied directly from subreddits like r/me_irl or Weird Twitter accounts like @dril. In an attempt to preserve the group’s originality, the mods began temporary prohibitions on certain kinds of memes: an image ban, a Tinder screenshot ban, and so on. Posts that did become popular often ignited debates about oppression and identity, like the aforementioned scuffle over appropriation and racism in “dat boi.”

During a particularly bad fight earlier this summer, a division emerged between old and new mods. The older members felt they had a unique ability to understand the kind of content that made the group successful. Corey Blackburn, a longtime creator in Post Aesthetics and a member of the Chicago Long March Reenactment Society, was one of them. “The group had grown stale, content-wise,” Blackburn said. “There were times when phenomenal original content would be drowned out or overlooked by people posting ‘the week’s hit meme’ exclusively to acquire digital capital.”

The newer mods argued for their relevance and originality. They’d been given power because their contributions had helped the group evolve and grow. They were more representative, too: as debates over identity politics influenced the selection of the newer mods, more diverse members gained power to police the group. These new members argued that there can never be one universally agreed idea of what makes a piece of internet content worthwhile. “The concept of ‘good content’ is subjective,” wrote Ena Da, one of the leading newer mods. Anyone who would claim “ownership of the concept,” Da argued, would be “acting more out of elitism and entitlement” than care for the Post Aesthetics community.

In time, the division deepened from an internal squabble into a flame war. Some members began doxxing others, digging up personal information that could be used against them offline. Older mods began to call for Post Aesthetics to be dissolved, and gained the support of the group’s creator. In what Blackburn euphemistically described as a “semi-democratic decision,” the older mods banned all of the newer mods and replaced them — with some of the members of the Chicago Long March Reenactment Society. The remaining mods appointed a single all-powerful “administrator.” This administrator promptly initiated a script that would automatically delete each of the forty thousand members of the group — as well as all the content and community they’d created.

“I do not want to punish the 40,000 members of Post Aesthetics for having been in the so-called out-group,” Ashely Li wrote as the script slowly worked away. “Precisely the contrary: I want them to recognize the contradictory character of their own group, their potential for self-overcoming, and to join me in building something new from the ruins of the old counterculture.” The memetic Marxists had won, the coup was complete, and Post Aesthetics was no more.

It’s hard to take the decline and fall of a meme empire very seriously. But you know that social media — despite its purported mission to help people connect — just as often leads to isolation, jealousy, resentment. The improbably real community of Post Aesthetics fought against that. Its spirit continues in various places, including in a large, successful splinter group founded by the writers of the Jeb!/Hamilton musical. Still, the inability of 40,000 bright kids to figure out a way to govern themselves doesn’t bode particularly well. As this election season has proven, social media and memes can be powerful political forces, made even more powerful when they’re uncritically overused.

But here’s the thing: Post Aesthetics was critical about online content. Entire groups emerged just to critique it! All of the members recognized they’d made a community that was actually worth preserving in some reasonable way, and fought hard, though unsuccessfully, to see their visions through. I asked Corey Blackburn if he thought it was ultimately possible to govern an online community as large and dynamic as Post Aesthetics. “Absolutely,” he said, “but governing it with explicitly democratic ideals and maintaining an open-ended environment and maintaining safe space policies and not pissing off weirdos who would want to harass you in ways that might affect your real life? Not possible.”

“But,” he added, “I don’t know if I’d want to be in a group where it is.”