Help Wanted: Seeking Young Hemingway To Cover Retired Americans In Belize

Dublin was busy with construction and slick with rain. I tried to recognize landmarks through the taxi windows — mossy stone gate here, mossy stone church there — while the cab driver told me how the Irish were all getting rich and he had finally been able to move back home from the impossible hell of Scotland. It was the end of 1999, I had just flown from Washington to interview for a magazine called International Living, the new hotel-pub where I was staying was owned by someone from the band U2, in 24 hours I would be back at the airport, and life felt like a Thomas Friedman column.

The registration desk was also the bar, so I had a pint and read the newspaper’s literary supplement, which started with an essay about the Gospel of Luke, by Nick Cave. The pub was new, like the hotel, but it was designed to look old like any Irish pub in San Francisco or Central Europe. After checking into my room and showering away the airplane grime, I walked through the rain to Trinity College and poked my head into bookshops and bistros. And like any other old city I’ve ever visited, within a few minutes I had decided this was an ideal place to live. I was even a partial Irishman, on my maternal grandfather’s side, and the Irish were coming back to Ireland. The Celtic Tiger, as the business reporters called the bubble economy here, was on the prowl.

The editor met me at the pub. She was American and about 30 years old, as was her husband who tagged along and also worked for the company, and they were both enthusiastic and friendly. The publisher was actually based in Baltimore — an hour away from my apartment in Washington. And the publisher was really a direct-mail newsletter marketing company that sold package tours to cheap countries where retired Americans could live on less money. I heard this, but what I believed was the Help Wanted ad I’d seen in Editor & Publisher. Like all newspaper people looking for work, I had subscribed for six weeks of the print edition, which was impossible to find in libraries or at newsstands.

The ad went something like this:

LIVE YOUR DREAMS: Seeking excellent writer and reporter for international magazine aimed at expatriates and frequent travelers. If you can travel the world and write like Hemingway, send your best clips and ….

As we talked and drank Guinness, an independent observer would note that we were not exactly having the same conversation. It didn’t occur to me that the editor had used “Hemingway” to mean a writer for a subscription newsletter, the way “Picasso” is shorthand for artist. I was thinking of Hemingway’s feature writing he did while in Europe, before his fame as a novelist. There was a collection of this stuff called Byline: Ernest Hemingway, and I naturally assumed any editor who mentioned Hemingway would also know and love this book. Wildly over-interpreting a simple classified ad, I decided they really wanted a very good writer to write literary journalism (and daily updates for their email newsletter), and had searched the world and come up with … me.

The job really did require traveling around the world, and they really did put together the monthly newsletter in a drafty old Irish mansion. This was all very romantic, regardless of the type of publication.

On the plane back to D.C., I had a middle seat in the middle row smashed between two enormous Irishmen who reeked of whiskey and snored and farted for the entirety of the five-hour flight. I couldn’t have been happier. With the overnight trip to Dublin concluded and a formal job offer in the mail, it was just a matter of giving my two-week notice to UPI behind the White House and beginning this new career as a globe-trotting correspondent — and it was a good time to leave, as the Reverend Moon had just bought the fading old wire service from the Saudi princes who had tired of throwing their millions at United Press International, and all my friends on the news desk were moving on.

Besides, I had just started a twice-monthly humor column for a mysterious website called Getting It, edited by R.U. Sirius and funded by a pornography company in Florida. They paid a dollar a word. Considering I had spent the last years of the 1990s working without any pay at all, the prospect of two reliable writing incomes was almost too much to believe.

I was in Spain on my first vague assignment for the expatriate newsletter, fighting with foreign phone plugs and AC adapters and Compuserve dialup, when I finally managed to get email to download. The first message was from Mat Honan, my editor at the webzine in San Francisco. His brief note said something like “Sorry, they’ve pulled the plug on us.” My tenure as a well-compensated dot-com humor columnist had lasted exactly six weeks, or for three entire columns.

The next message was a forwarded collection of people griping about my contributions to the International Living email newsletter. “THIS SUCKS” was a common refrain. It was the first hint that I didn’t at all understand the nature of the job, which had never really been explained to me but probably required a lot more “buying cheap real estate in foreign countries” information than I had provided, which was “none.” The fact that my rental car had died in the industrial shipyard district of Cartagena, far from the southern beaches I was supposed to be scoping for affordable retirement homes, did not help with the daily content.

But there was time to redeem myself in this last remaining job. I would accompany a tour group to Central America and write it all up for the newsletter. On a January afternoon I landed in the former capital of Belize City, which was not a city at all but a small inland slum. Another hurricane had just blown through and the public phones didn’t work.

British Honduras had been a libertarian/pirate paradise during its British colonial history, and the old Belizean capital was about what you would expect of a pirate town in the year 2000: brightly painted plywood shacks and half-built cinderblock shops selling bootleg copies of Windows 98, mud roads and goats standing atop rusted cars, the descendants of slaves and pirates gossiping in the streets. It was delightful, but it wasn’t what brought the tour group to Belize. Our schedule called for dinner and then a short flight across the water to Ambergris Caye with its white beaches and American retirees.

Dinner, in a very plain restaurant lit by rows of fluorescent lights, was where I first met my traveling companions, all retired or close to it. We had fish and rice and beans while they gave their reasons for fleeing America. It was too expensive, health care would bankrupt them all, drug gangs were taking over, Clinton was sending the good jobs to China, and these new hippies were going to riot nationwide like they’d just done at the World Trade Organization conference in Seattle. Stocks were falling and the dot-com bubble was about to pop. And all over the world, in quiet little towns, expatriate Americans were living the kind of retirement they deserved, with money for eating out and other retired people for socializing and very affordable housekeepers and prescription refills. The problem was that the retirement colonies quickly developed reputations and then the prices shot up.

“Developers buy it up and triple the prices soon as they see some old people with yankee dollars,” a round little Italian-American from Philadelphia told me. “That’s why you got to constantly be looking for the next place.”

He called himself Danny, and I guessed he was one of the developers, or at least the eyes for a developer, but it was just as possible he enjoyed planning for a variety of retirement scenarios in exotic locales. And he made too many Mafia jokes to have actually been in the mob, maybe.

The others were all polite, and the ladies were generally friendly. The men were American men, mostly born in the 1930s and not ones for small talk. Danny was my favorite, with his ongoing narration of events as they happened. When a waiter screwed up and brought the salads after the meal one night, Danny went into a long monologue about how his dear Sicilian mother had always served the salads last, too. It helped with digestion, he said, “to push the meatballs down.”

After the guests were safely escorted to their overnight lodging, I went bar hopping with the tour guides, two girls from Florida. There were three or four main bars, in various stages of disrepair. At one palm-roofed shed where that Macy Gray CD was playing on repeat from a boombox behind the bar, I got into a conversation with the kind of blond neo-hippie guy I always run into at the end of a night abroad. He was a straggler from a bunch of American or Canadian backpackers, and he was barefoot and wearing a yellow and red Garifuna women’s headdress somewhere under his dreadlocks.

The conversation ended with the usual, “Well sure, I would like to get high,” and then we were moving through alleys and under corrugated steel corridors. It took a while to reach the mahogany jungle at the edge of town. The shacks were smaller and sparser here, and I sat cross-legged on the dirt outside the shed of a very old man, with a white beard over black skin, dreads of his own tied up in a rag.

“He doesn’t talk,” the hippie said. “But he knows things. He knows everything.”

I nodded and took a newspaper joint the size of a hot dog from the old man. To this day, I have no idea what was in that thing. But when the hippie began whispering about how the old man can control space and time, I listened intently because I was trying very hard to concentrate and not to fall over.

“Look at those clouds,” the hippie said. Above us, scattered clouds moved through the moonlight. “He can make those clouds go back.”

And sure enough, because I was extremely high, when the old man stared up at moon the clouds appeared to reverse direction.

“That would be one hell of a superpower to have when the next hurricane comes through here,” I said. The hippie nodded and smiled. He and the old man both had their eyes closed now, I don’t know for how long. Somehow I made it back to the center of town and my hotel, which was exactly one block away.

I spent the next week tagging along with the retirees on Ambergris Caye, where I snorkeled the reef with giant stingrays, and flying to uninhabited beaches being subdivided. Walking along a proposed development on shore of Placencia. Danny was dubious.

“You move out here, you look at the pretty view of the water, how long does that last? A week? Then what the hell do you do? You move down here with the wife and she’s looking at you and you’re looking at the water and where do you even go to have a coffee?”

Still, for about $40,000 total, a beach house on Placencia was a good deal. Freshly printed brochures were passed around and some contracts were signed. The tour ended after a stay at an “eco resort” in Guatemala. Except for the giant spiders crawling all over my bed and ceiling and bathroom towels, the place was all class. I made my way up to the Costa Maya and hung out for a few days with a friendly American developer who was building his own retirement village on the southern end of Mexico’s Quintana Roo. He would call his development “Coconut Beach,” he told me, because his clients “wouldn’t understand these Mexican names.”

One of the very many times I’ve questioned my career choices was when this wealthy developer praised my Spanish at a restaurant in the fishing village of Majahual where we’d stopped for lunch. I cannot speak Spanish, but he didn’t know a word of it. He didn’t need it, didn’t want the obligation, and people called him “Mister” wherever we went — even the American surfer who was enraged to see this well-known Yankee real estate man scoping out these secret beaches along a dense forest full of coatimundi and howler monkeys.

I wrote up many thousands of words, enough to fill two monthly issues of the newsletter, and did my best to speak the language of retirement to these people paying good money for informational newsletters. Still, I didn’t even have a credit card in the year 2000, let alone a savings account or 401K or a car or much in the way of Social Security contributions.

As commonly occurs when people are compelled to interact, the newsletter editor and I were both convinced of the other’s shortcomings. But we parted ways peacefully. It was time to leave this short stint as a retirement-community journalist and return to something I really disliked: American politics.

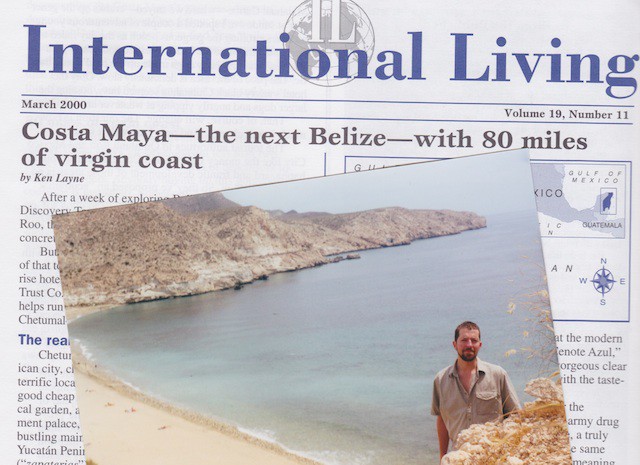

The author on retirement-village assignment in Spain, in November 1999, and his final byline for the newsletter.

Related: How To Fail At Journalism In Exotic Foreign Lands

Ken Layne has held approximately a hundred media jobs around the world. He should’ve learned by now. Photo of spider monkey in Belize at top by Jon Robson.