"It's All Coming Back to Me Now" is a Very Weird Song

The third single from Céline Dion’s 1996 “Falling into You,” is a ballad for a corpse.

On July 30, 1996, Céline Dion released the third single from her incredibly successful album, “Falling into You.” The single, “It’s All Coming Back to Me Now” was a hit, ultimately peaking at number two on Billboards Hot 100 chart. But dear God, was it ever a weird song. Selected as the leadoff song on the album, it’s placement both as a widely released single and as the introduction to Céline’s most-popular album brings up one really interesting question; who starts a mainstream, 90s “adult” (i.e., mom) pop album off with an abnormally long ballad about dancing with a corpse? Whoops, may have jumped too far ahead there.

To begin with, the album version is seven and a half minutes long. This may not seem like an exceptionally long song, but for a mid-90s pop hit by Céline, this is downright epic. The widely released version you’re probably familiar with was cut down to a more radio-friendly five minutes and thirty seconds, but even then, this length is nearly unprecedented for her. Her second-longest song, “Us,” clocks in at five minutes and forty-five seconds.

“It’s All Coming Back to Me Now” was written and produced by Jim Steinman, a longtime songwriter for Meatloaf, which now makes it impossible to hear the song as anything other than a Meatloaf song. This was the only song Steinman wrote for her “Falling into You” album (though he helped produce a few others). He specializes in crafting huge, melodramatic ballads, so a singer with the vocal range and the ability to express powerful, life-and-death emotions like Céline is a necessity for him. Steinman also wrote “Total Eclipse of the Heart,” and, apparently, a theme song for Hulk Hogan in the ’80s. He only does things one way: over the top and incredibly emotional.

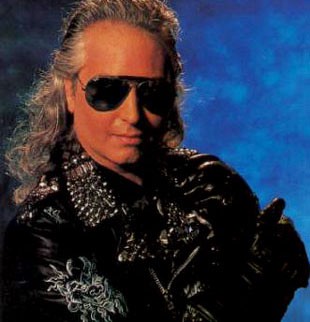

On his very outdated website, Steinman describes ”It’s All Coming Back to Me Now” as “an erotic motorcycle.” Steinman himself always dressed as a kind of gothic, leather-clad biker. Later on he’d pitch this imagery to the director of the song’s music video, Nigel Dick, who really doubled down on the idea.

Steinman also says on his website that he wrote the song, “under the influence of Wuthering Heights.” This checks out — the song is melodramatic and tortured as hell. Consider the first verse:

There were nights when the wind was so cold

That my body froze in bed if I just listened to it

Right outside the window

There were days when the sun was so cruel

That all the tears turned to dust

And I just knew my eyes were drying up forever

The song goes on to paint the picture of a narrator who “banished every memory you and I had ever made,” likely due to the fact that the relationship was a very abusive one. A later verse explains:

There were those empty threats and hollow lies

And whenever you tried to hurt me

I just hurt you even worse and so much deeper.

That’s not great. While this does bring up the specter of physical abuse, with all the context around the song, it seems more clear this is a kind of obsessive, emotional abuse. Steinman explains:

It’s like Heathcliffe (sic) digging up Kathy’s corpse and dancing with it in the cold moonlight. You can’t get more extreme, operatic or passionate than that. I was trying to write a song about dead things coming to life. I was trying to write a song about being enslaved and obsessed by love, not just enchanted and happy with it.

He felt so strongly this song should be performed by a woman that after writing it, that he sat on it for years, allowing only and obscure girl group “Pandora’s Box” to record it. You know who that pissed off? Meatloaf, who (correctly) thought it was the perfect Meatloaf song. Steinman wasn’t having it though, and as the dispute over the song’s usage ramped up, he took Meatloaf to court to block him from recording it. Eventually, Meatloaf did end up recording a duet version of it for his 2006 album “Bat Out of Hell III: The Monster is Loose,” but his version can’t hold a candle to Céline’s.

Céline is an archetype — the embodiment of the squeaky-clean diva. She sang THE ballads of the ’90s: “Because You Loved Me,” “All By Myself,” and (cue the tin whistle) “My Heart Will Go On,” probably the biggest ballad of the decade with the possible exception of Whitney Houston’s “I Will Always Love You.” Throughout her ’90s peak, Céline belted those ballads out over impeccably manicured soundscapes, full of breezy drums, watery acoustic guitar and choirs — oh, the choirs — backing her up. Her persona was essentially being as agreeable as possible. Even now, hunkered down in Las Vegas, she’s the clean, family entertainment option within the city Gil Grissom swabbed.

The only genuinely weird thing most people knew about Céline was her marriage with her late husband and manager, René Angélil, who was 26 years her senior and first met Céline when she was only 12. They maintained they didn’t begin dating until she was 19, and there’s not much internet controversy around it, so there’s no reason to believe that isn’t the case. But it’s the only thing that sticks out about Céline’s well-manicured persona. When Céline was at the peak of her powers in 1996, she was 28. Her husband was 54. Kind of weird?

Other than that ONE THING, though, Céline has a pretty spotless reputation. Which is one of the reasons why having her sing this song is so odd. The theme behind the it — even Steinman himself — it’s all so much different from her usual material. She obviously has the vocal ability to get through the marathon performance, but no other songs in her catalog touch on such deep-seated passions, for lack of a better term. The other singles from this album, “Because You Loved Me,” “All By Myself,” and the title track of “Falling into You” are powerful ballads, but they kind of deal in surface-level emotions. “Because You Loved Me”’s main thesis statement is basically, “things were tough for a bit but you were there for me and now things are great, thanks!” Which is a good message plenty of people can relate to, but this is so much different from “my eyes drying up forever.”

The first minute-plus is instrumental, detailing that something catastrophic is happening. Piano chords ring out, and the melody is slowly tapped out. Suddenly, a drum strike, accompanied by the sound of crashing thunder — things are not currently so great. For this portion of the song, the unintentionally hilarious music video posits a motorcycle crash; the death of Céline’s lover as he recklessly speeds away on Steinman’s “erotic motorcycle” in the rain, only for a strike of lightning to knock a tree over, fall into the middle of the road and catch on fire. There’s an explosion. He doesn’t make it. But, he comes back to haunt Céline/drive his ghost motorcycle down the hall in special effects worthy of the finest episode of “Are You Afraid of the Dark?”

After this set-up, we move from a slowly building verse, to a heightened pre-chorus, to the explosive “baby, baby, baby!” and then the chorus, which Céline really belts the hell out of. It’s an incredibly cathartic moment. How do you follow up that crazy crescendo? Silence settles in. It lingers. Then, the song just kind of starts back up again, repeating the same structure with some new lyrics in the verse. A new fuse is lit, before exploding in the chorus. Only this time, rather than silence at the conclusion, there’s a very slow fade out where Céline gently whispers the chorus and piano keys twinkle us out…. and onto the remaining hour-plus of remaining album, if you’re a Céline album purist.

Most ballads don’t do this. The format is generally a slow burn, going verse/chorus/verse/chorus/bridge and then, finally, BOOM, the payoff: the chorus explosion where the singer really lets into it. Think “My Heart Will Go On,” or yes, the best example of this form, Whitney’s “I Will Always Love You.” The reason to listen to the latter isn’t the random saxophone solo in the middle, it’s the one iconic drum sequence followed by Whitney letting loose in a way which I won’t even attempt alone in my car. I just silently nod in respect.

“It’s All Coming Back to Me Now” ignores all of this. It doesn’t build to one payoff; it is essentially itself one long payoff. It’s operatic. It’s melodramatic. It’s written by a guy who looked like this:

The entire thing screams excess. A song ostensibly about (metaphorically, but still) digging up your loved one’s corpse and “dancing” with it became one of the most popular songs of 1996, ending the year at number 18 on the Billboard Hot 100. The music video features a ghost boyfriend who just doesn’t know when to let go.

So often, pop ballads seem to have come off a conveyor belt, designed for maximum appeal by multiple songwriters with minimal risk-taking in the composition. It’s all carefully processed to gently play in the background of your commute. But occasionally, you get truly unique weirdos like Jim Steinman and songs like “It’s All Coming Back to Me Now.” Céline was really going for it in 1996, and she made the decision to have this tune kick off her album. How incredibly bold! She didn’t play it safe, at all, and she was right. I’ve been listening to this song on repeat for weeks now and I have to say, it’s a thrill. That Jim Steinman, he’s just a mad man with an incredibly unique style and sound. Yes, it can sound like a bit much at times, but the grandeur of it all is a little bit intoxicating. Sometimes, I just want to sit back, put on a song like this, and be taken on an epic, slightly cheesy ride for almost eight minutes.