Home Away From Home

by Carter Maness

The twenty-something looked the part: dirt-streaked face, shoe tongue dragging on the pavement, a Sapporo tallboy so empty it rattled when he walked. In Tompkins Square Park, the outdoor barometer of homelessness in the heart of New York City’s East Village, a camera crew filmed his descent into squalor. He was trailed by a sound guy with a boom mic angled to catch a nearby jazz band flying through a madcap version of “Cherokee.” The director sat in a wheelchair, being dragged backward to ensure the smoothness of his shot.

Filming a fictional march to destitution six hundred feet from real suffering bordered on cruel irony. The very real homeless encampment at 7th Street and Avenue A freaks people out. Busted suitcases, junked bikes, tarp-covered mats, and shopping carts piled high with threadbare clothing insult the bougie sensibilities of the neighborhood’s newer locals, as well as the New York Post, which last July published an alarmist feature warning the park was being overrun. (It was written and reported by five people, but the way it reads, only of one of them appears to have visited the park.) The NYPD responded by installing a panopticon; barely a week later, it was sheepishly removed. Homelessness has been on constant display at Tompkins Square Park for decades; its presence symptomatic of how, in a given era, the city responds to and helps its least fortunate.

Kathleen and Clarence (not their real names) are longtime East Village residents and regulars at Ray’s Candy Store, a legendary storefront on Avenue A that specializes in Belgian fries and ice cream. They told me things have gotten worse.

“They’re younger and have more privilege,” Kathleen said.

“Yeah, and those guys with the dogs,” said Clarence. “What are they called?”

“Crust punks?” I offered.

“Yeah, crusties! A few weeks ago I saw a black car pull up. Man gets out, hands money to one of these crusties, and they drive away.”

Kathleen laughed. “Their hustles stay the same, though. They come in here, order fries, and, when Ray walks to the back, they hop the counter and clean out the register.”

Like the version of New York de Blasio vowed to end, Tompkins Square is a park of two halves: one cardboard, the other beach blankets. The homeless side, which contains the encampment at 7th and A, extends up to 9th street along the park’s western corridor. I’ve been spending afternoons there since December. Two weeks ago, as the weather turned warm, I saw people bumping fists, playing chess, sharing coffee. They gossiped about phones — what SIM cards might work for the models they found. Even the meadow, the park’s grassy center where people sunbathe, adheres to the fault line. On the west side, a homeless couple smoked a spliff, resting their heads on Duane Reade bags packed with clothing. On the east side, tourists paged through guidebooks. Couples made out along the border of a dog park filled with handsome pets.

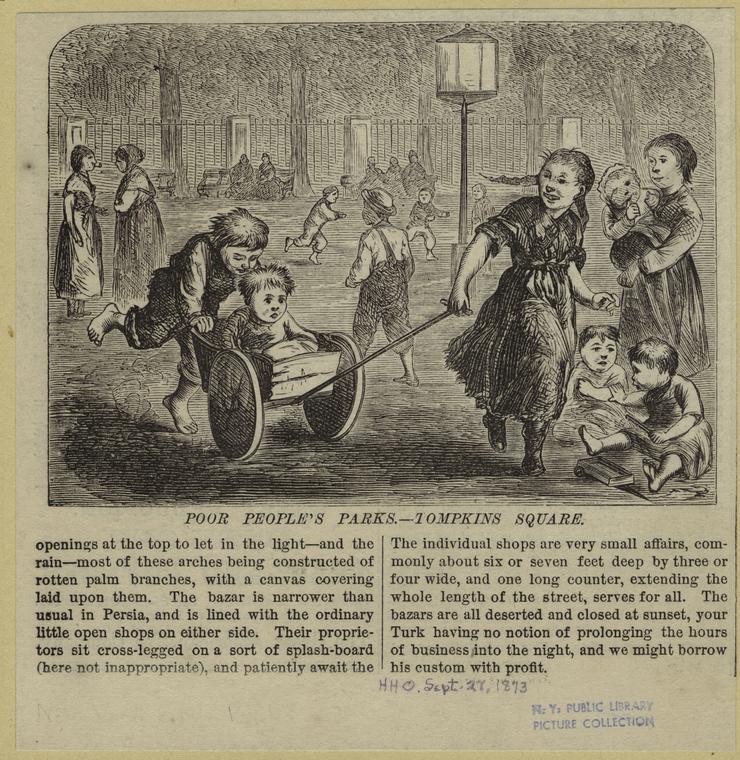

Tompkins Square Park has been a mirror for the city’s social issues since the Stuyvesant family was paid $93,000 for its land in 1834. The park, named after former governor and Vice President Daniel Tompkins, has always been a place for local communities to gather, whether Germans in the mid-to-late 1800s or the influx of African-Americans and Puerto Ricans in the 1950s. Counter culture bloomed in the sixties, especially after the park’s bandshell was unveiled in 1966. It was a central location for activism and performances both local and, in those early days, from bands like the Grateful Dead.

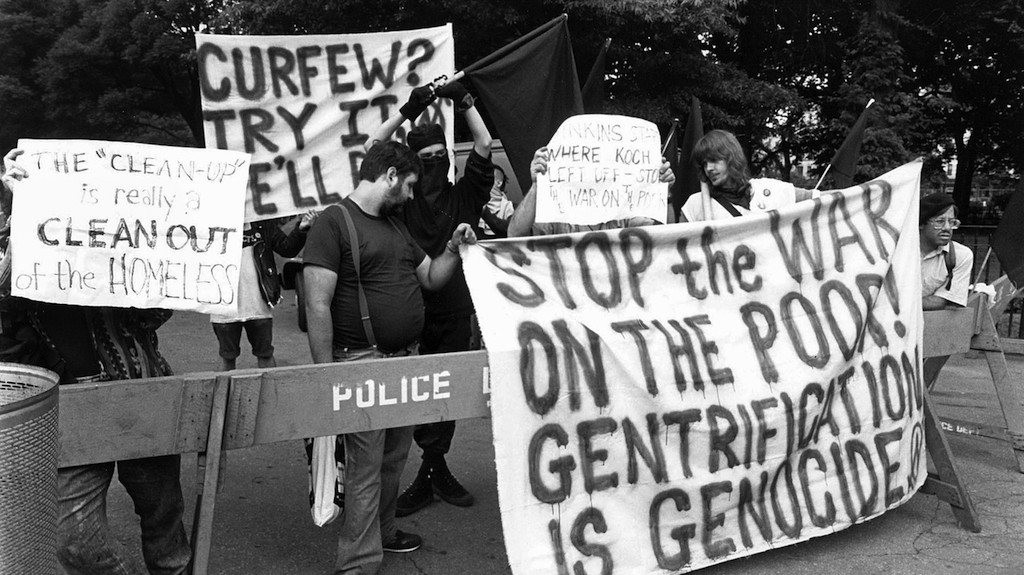

Homelessness skyrocketed in the 1980s, when a broke city couldn’t afford to provide adequate housing for its most impoverished citizens. Tent cities sprang up in the park. Drugs were sold and abused, and residents — torn between supporting their own and disgust at the noise level (not so much the poor sanitation or vagrant populations) — complained to the administration of Mayor Ed Koch. In the summer of 1988, tensions boiled over after Manhattan Community Board 3 voted on June 28th to install a 1am curfew (the park had been open twenty-four hours for its first hundred and fifty-four years). On July 11th, the NYPD carried out major overnight eviction, clearing out all non-homeless residents and sequestering those with nowhere to sleep in the park’s southeast corner. On the night of August 6th, tensions exploded as the NYPD stoked a riot, responding to thrown bottles with overt force, in many instances hiding and removing their badges while they clubbed bystanders. By 1990, the tents were forcibly removed. Some homeless protesters burned their shelters in defiance of the city’s treatment.

The 1988 riot in Tompkins Square Park, NYC Parks Department.

On June 3, 1991, acting on orders from Mayor David Dinkins, three hundred police officers surrounded the park. Under the guise of a $2.1 million renovation, they dismantled all remaining homeless encampments and built a plywood fence to signal its closure. When the park reopened in August of 1992, the bandshell was removed, the pavement powerwashed, and the homeless siphoned into federal housing programs, shelters, and less visible pockets across Manhattan. Removing the centralized hub for social services provided the appearance of a cleaner East Village. But when Dinkins left office in 1993, there were twenty-three thousand homeless people, a near twenty percent increase from his inauguration, and a number that held steady through Giuliani’s broken-window nineties, when the homeless were routinely sent to the Tombs for minor infractions.

In addition to a consistent increase in homelessness through Mayor Mike Bloomberg’s first two terms (and despite his administration’s policy of gifting one-way tickets out of town), there was a massive spike following the 2008 financial crash — a combination of gutted programs and job loss left an unsustainable number of New Yorkers without a permanent residence. There are now fifty-nine thousand homeless people in New York City shelters each night, an increase of about six thousand from that time, during which the mayor cut nearly every safety net available to the homeless. It’s hard to get an accurate number, but just under three thousand people live on the streets, according to the latest Homeless Outreach Population Estimate. That’s down twelve percent from the previous year, which made for big news, but most homeless are in and out of the shelter system, which, even before recent slashings, garnered a universal reaction from the community: Way too dangerous.

The week before Christmas in 2015, Mayor de Blasio responded to growing concerns about homelessness by creating HOME-STAT, a program that tracks real-time complaints and placed five-hundred additional canvass workers covering every block between 145th and Canal Street. It also added quarterly nighttime surveys in addition to the annual HOPE count each February, as well as a systematic review of how the homeless population spiked. By April 6 of this year, de Blasio merged the city’s agencies for homeless services and welfare into a body led by Steven Banks, then commissioner of the Human Resources Administration. He announced the program’s official launch at Tompkins Square Park just after a mentally ill homeless man was forcibly removed from the area. Tabloids seized the opportunity.

There was a large flock of pigeons near the encampment where I met Tommy, a man with epilepsy who has slept in the park on and off for the past twenty years. The birds tore at bread and seeds, erupting in flight each time someone passed. To my left, drying clothes were hung over a wrought iron fence, and a man held a shirt to the sun to check for stains. A woman, screaming “She stole two motherfuckin hundred dollars from me!” had a black cocktail dress slung around her neck.

“They rob you,” said Tommy when I asked him what happens when you sleep in the park. “People take advantage of you. If there’s anything to steal, it’s gone.” I asked where he would go to be safe. “When the cops chased me out, I slept by the waterfront by NYU.” I realized he meant NYU Langone, the hospital, which borders the East River off 30th Street.

With help from YAI (The National Institute For People With Disabilities, originally founded as the Young Adult Institute), Tommy has received both rent and food assistance for the past six months. He now has a Section 8 apartment, affordable housing south of the park “near the electric generator.” He told me it was a blessing to have a door to lock his possessions behind, and that missions (Bowery), ministries (Food For Life, Hope For The Future), and nonprofits routinely came by to provide hot meals, sandwiches, and coffee. The whole time I was there, not fifteen minutes passed without seeing an outreach worker or police officer extending a hand. The cops knew the regulars; they greeted everyone with empathy and warmth.

Tommy introduced me to his best friend, Brown, who sits in the park every single day, “even in the rain,” and to whom Tommy lent his last two dollars so he could buy a kind of synthetic marijuana called K2. Brown, for lack of a better term, was weathered as fuck. Born and bred in Crown Heights and a resident of the East Village for the past six years, he stared at some nameless thing in the distance. I asked if the park was more of a community than outsiders might realize.

He shook his head. “Every man for himself in the park.”

“There’s some good people and bad people,” said Tommy. “I’d rather root for the good people.”

I exited at 7th and A, where a crust punk was unzipped. He openly scratched his balls, but looked ashamed when we made eye contact. Off 9th Street, where I stopped to inhale a Superiority Burger, a duo of undercover cops were cuffing two homeless men. One of the cops wore a hoodie that said “Brooklyn 💓.” At 9th and B, two lines had formed. A community church was giving out coffee and Entenmann’s pastries. The lines were completely segregated: one, which was served first, was mostly men, all speaking English. The second line was all Chinese women and Spanish speakers.

On the corridor that runs parallel to Avenue A, Diane Dunne was setting up for her Church Without Walls. Pastor Diane, as she’s called, has run Hope For The Future Ministries since she quit her job as a cosmetics executive in 1987. Each Wednesday and Saturday afternoon, she preaches her own brand of radical Christianity and feeds a multicultural congregation of the homeless and hungry. Volunteers prepped for communion — wafers and juice poured into flimsy paper condiment cups — as Dunne greeted her parishioners with hugs and shouts of encouragement. Her crew distributed songbooks, New Testaments, and bottles of soda: Mountain Dew, Diet Dr. Pepper, and Lipton Iced Tea.

Dressed in a crisp blue leather jacket and purple shirt, she took the microphone. “Has everybody got their sodas?” She immediately launched into a version of the Hava Nagila. “Jewish people do Passover every year,” she said. “And they don’t realize they’re talking about Jesus!” A lumbering man who looked like he could have been a biker in a past life nodded to me to me as I watched. He said, “A lot of my friends have been fed by her in times of trouble. You wouldn’t believe the hate she receives. Somebody punctured her tires a few weeks ago.”

After the service, which featured tambourines and a raucous version of “Our God Is An Awesome God,” Dunne’s crew distributed food and communion to everyone in need. Brown stayed on his bench, but Tommy grabbed enough to eat for both of them. The “optics” of this kind of visible homelessness seem bad to people with money. But the homeless continue to gather at Tompkins Square Park because it provides a centralized point for social services. Their numbers serve as a consistent reminder of the city’s responsibility to create permanent assistive housing for those in need. Their presence maintains a whiff of protest against the delusion that if homelessness is made invisible, it has gone away. Tompkins Square Park is a place for people, especially those in need. When their numbers swell, it is not a spill to clean up, but a reminder of how much more there is left to do.