Understudies! The Darkness of 'Annie,' Ginger Queen of Poverty

by Angela Serratore

Listen in on a certain variety of college-age girls who are meeting each other for the first time and you’ll inevitably hear the boasts, the pride, the tentative assertions of superior talent that come with talking about what is, for these girls, the most important subject: who played whom in which high school and community theater musicals. There’s always a Maria, an Eliza Doolittle. The prim lanky ladies are a Sally Bowles (they come from an experimental charter school and have boundary issues) and there’s the Rodgers and Hammerstein girls who went to Catholic school and are in awe of the worldlier, more sexualized characters their peers were allowed to play.

At some point, someone will pipe up and announce that she, too, has starred in a musical production. She’s put on a wig and stage makeup and a battery-pack microphone and neglected her science homework for weeks on end to learn a dance routine. She has won the hearts of parents and teachers alike with her charm, her clear-as-a-bell high notes, her ability to emote for the seats in the back.

And then, Little Orphan Annie gets laughed at.

Annies are a sisterhood united in red wigs, misbehaving dogs and a devastating lack of respect from cooler, more adult stage characters. Some of this, to be sure, is because “Annie” happens largely in elementary schools, years away from the stolen cigarettes and kisses that make up so many high school musical theater memories. Annie, you see, is literally child’s play, by and for a group of people not old enough to see “Cabaret” without a parent or legal guardian-and for that Annies are punished.

You know what? We’re sick of it.

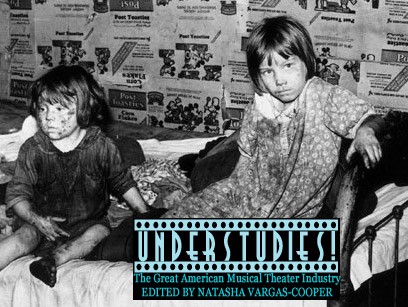

“Annie” is a musical that doesn’t quite fit into any established category. It’s not a comedy, no one dies, and the center of the story isn’t unrequited love but poverty, both of wealth and affection. In addition to these grim qualities, it is terrifying.

Annie and her friends, as you may remember, live in an orphanage, and yes, they sing songs and dance up and down the stairs, but the songs are about hard labor and the dances are elaborately choreographed escapes from Miss Hannigan, the drunk warden who abuses the kids and does a very peculiar and highly sexualized song and dance routine with her brother.

Annie longs to reunite with her birth parents, but unlike the wealthy orphans of The Little Prince or The Secret Garden, cared for by elderly grandmothers and their butlers, Annie is stuck in a tenement house in the New York City of the 1930s, which communicates to everyone but her that her parents are dead, destitute or both.

Also, everyone Annie meets-besides Daddy Warbucks, Miss Farrell and FDR-is a hobo!

It’s dark stuff, and yet! Reviews good and bad always seem to judge the show based on its appeal to families and children. A 1996 production starring Kathie Lee Gifford as Miss Hannigan (and here you thought no orphanage head was more likely to eat her charges than Carol Burnett in the 1983 film version) was praised by the New York Times as “an elating piece of family theater that deserves to become the mass-entertainment holiday staple it aspires to be.” A year later, though, a new Broadway cast was called charmless and antithetical to the show’s “perky, crowd-pleasing roots.”

It is apparently impossible that a show starring children, some of whom, yes, are indefatigably optimistic, can also be scary and real and a reflection of how precarious life for the Other Half is in times of economic hardship and national malaise.

There’s also the problem of “Tomorrow,” the song most associated with the show and the Pollyanna qualities that have shunted it into the “musicals for children” category. Yes, it can grate, and yes, there isn’t a whole lot of subtext (okay, there is no subtext) happening, but it’s also really powerful! An abandoned child who, until recently, had never gone to bed without hunger pangs is singing, on the radio, for the sole purpose of brightening the nights of people who are jobless, who are poor, who are hopeless-people who are, in fact, no different from the same people that were forced by the same circumstances to put her in the orphanage in the first place. It is not sexy, and it is not mournful, but it is pure-not an expression of feeling from singer to audience, but a chance for audience to express feelings of their own.

When it was announced that “Annie” would be returning to Broadway in 2012, something shifted. I have yet to read anything mocking the show’s reappearance, and perhaps more encouraging, critics and fans alike seem to realize how exceptional the timing is. The Great Depression feels closer now than it did in 1996. We as theatergoers might be ready to see the show not as a glorified pageant for children, but as something closely resembling our own realities, if enhanced by tap dancing. And, in what is a true vindication for Annies everywhere, the original Annie, Andrea McArdle, is taking over the role of Miss Hannigan, inspiring a slew of “day after ‘Tomorrow’” headline puns — and not one joke about red wigs.

Angela Serratore is a writer/historian in Los Angeles, and has played Annie-twice!