Booktorrent! The Bookmobile as Rural Filesharing Network

by Jane Hu

In the 1908 booklet Books for the People, the Midwestern librarian Henry E. Legler wrote: “Following in the wake of the great public library movement, which in less than two decades has dotted the cities of the United States with buildings that house millions of books for the people, came systems of traveling libraries.”

Legler was speaking of what we call bookmobiles, which began to connect the rural cities of America during the early twentieth century.

Since its development in the mid-nineteenth century, the American public library stood not only as a resource for books but also as an institution which mediated between a community and its knowledge. As they gained in popularity, libraries made edified and edifying conversations a part of daily American life.

Not merely a response to the needs of cities, the public library was partly a self-driven and active commitment to cultivate intellectually stimulated communities. There’s more than one way to look at that. In his lecture “Cultural Institutions and American Modernization,” Neil Harris proposes that the development of libraries in the late nineteenth century was “one of the movements of urban reform…[which] sought to impose the cultural and social norms of the upper class.”

Rural populations remained for the most part excluded. Too small to sustain local libraries, villages and towns could not access the same materials as metropolitans. The answer to this conundrum? Bookmobiles! Like the public library a century before, the bookmobile strove not only to deliver books, but also to develop an intellectual environment for its patrons.

The first American bookmobile came in 1905 when the head librarian of Washington County Free Library, Mary Titcomb, pioneered the mobile distribution of books across the county. With library janitor Joshua Thomas steering the horse-drawn wagon, Titcomb delivered boxes of books to “deposit stations”-the general stores and post offices of small towns.

Even before Titcomb began her delivery services, the response to this “first buggy book wagon” was met with positive cries: “Libraries to the people!” From then on, the popularity of the library wagon rose: boxes of 30 volumes each were sent to 66 deposit stations throughout Washington County. By 1912, automobiles replaced the original horse-drawn carriage. Without the physical limitations of animal-powered transportation, these vehicles carried even larger collections than before.

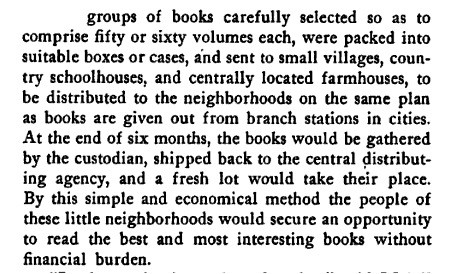

In his book Library Ideals, Legler describes how some of the earliest bookmobile were maintained:

Not everyone supported the passage of texts into small towns. Over in England, as early as 1825, Blackwood’s Magazine published an article that claimed, “Whenever a lower order of any state have any smattering of knowledge they have generally used it to produce national ruin.” It seems the political menace of placing a text in the “wrong” hands has always paid books the compliment of their influential force.

Rural librarian Patricia Salau lauded the cultural possibilities of bookmobiles:

Country people do not have other access to library materials…Frequently, their occupations do not encourage a cultural inclination, or an attitude of self-education…The bookmobile has to show country people that it is available for a range of topics beyond recreational reading, and further, it has to show them that it is useful to learn by reading and discussion, and to consider topics which don’t normally arise in their pastoral or small-town undertakings.

Despite the somewhat demeaning connotations of Salau’s description of “pastoral” or “country people,” her intentions are downright noble.

There was, of course, “good” reading and “bad” reading. One study of the time worried over farmers, who seemed to read only “bulletins and journals of agricultural practices,” while another warned against “penny dreadfuls,” which threatened “the youth of to-day, whose literary excursions will take him into the company of ‘Buster Brown’ and ‘Happy Hooligan,’ will have an even chance with the youth of a generation ago to develop into a useful and law abiding citizen?” Hey! I never realized how old this debate was either.

The influential public librarian Eleanor Frances Brown notes that although earlier bookmobiles were filled with “westerns, mysteries, light love stories, general fiction, a smattering of not-too-deep non-fiction, and a great amount of children’s material,” they progressively accrued intellectual texts of “abstract art” and “literary criticism.” She writes in Bookmobiles and Bookmobile Service (1967) that, by the 1960s, “there was little, if any, interest in the light and inconsequential.”

With the rise of bookmobiles, texts were accessible to an older generation who had never encountered libraries or any concept of information repositories. In one case, a….

woman sixty years old walked three miles over ploughed fields to get books, reading ‘Little Women,’ ‘Lorna Doone,’ and ‘The Vicar of Wakefield’ for the first time, catching up on all the reading she hadn’t had time to do in the first half century of her life.

The bookmobile also provided often-detached rural populations opportunities to socialize. In attempts to appeal to adults, bookmobiles often added late night stops. (I’m a little disappointed these don’t happen anymore.) The goal of the bookmobile to educate and thus “make better Americans” opened up a cultural conversation that spreads each day with the traveling word.

When I was growing up, my local public library would give out covers to hold our library cards. In one pocket, you would place your library card, and in the other, your bus pass. On the front, a happy slogan read: “All roads lead to the library.” Wouldn’t it be cool if the road was the library?

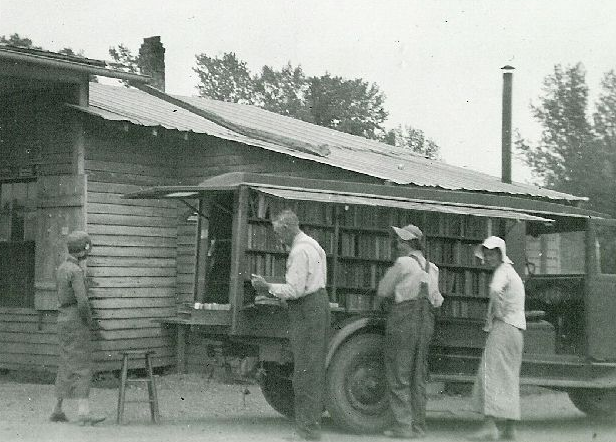

Pictured above: an early Davidson County, Tennessee, bookmobile; that county bookmobile service began in 1929.