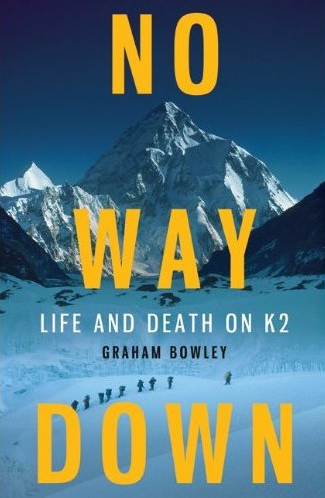

Six Minutes in Heaven: Graham Bowley, 'No Way Down'

by Evan Hilbert

Ways to die on a mountain: trip on a piece of ice; fall into a crevasse; lose your mind and wander the wrong direction; remain at high elevation for a sustained period of time; fall asleep; also, GET TRAPPED ABOVE AN AVALANCHE. Graham Bowley’s No Way Down is blurbed as “an Into Thin Air for a new century,” which is marketing whatever, and oversimplification of both works. Into Thin Air is a thrilling reported memoir told by Jon Krakauer after his disastrous Everest expedition. No Way Down is a reported story, borne from an article Bowley wrote in the Times two years ago. Bowley did not spend a second on the snowy, deadly cliffs of K2, in the expedition in August of 2008 during which 11 climbers died.

Instead, he uses an outsider’s perspective to tell the story of a group of climbers making a terrifying trip to the top of the world’s second-tallest mountain. Bowley’s reporting allows for a linear narrative explaining — nearly as possible — exactly what happened on K2.

We talked for six minutes.

Why do people climb mountains?

I think for many different reasons. On K2 I came across people who were doing it to escape their other life, escape their responsibilities —

Like a drug?

For some people it is. They do love that mountain and the escape, and I felt that myself when I went there last year. This summer, as the season has come around again, I really want to get back to the Karakoram. It’s very magical.

There was this married couple — -Cecilie and Rolf — -who could be together in the mountains, and that’s where they lived their lives. They were really interesting. It’s for achievement. It’s for patriotism. There was one guy — -Gerard McDonnell, a fabulous guy — -who died. He was there for himself, for his family back home and for Ireland.

I understand the escape and I understand the challenge, but is K2 a target because of the danger? Does that make it more appealing?

I think there are mountains, but K2 is special to certain mountaineers. While Everest has been overrun by the crowds, which it has, K2 has retained its mystique. It’s more remote than Everest — -it’s harder to get to. You have to go through Pakistan and trek for six days. It’s much further out. And then, when you get there, it’s deadly! So, people don’t go there. Only the really good mountaineers go there.

How did this go from a piece in the Times to a book?

I was sitting on the foreign desk when I wrote the story, and I went to Gerard McDonnell’s wake in Ireland and I saw a similar bewilderment amongst his family about why he had done this, why he had thrown himself on this mountain thousands of miles away. It raised all of these questions that I wanted to answer. So I set off to interview the survivors — -as many as I could — -and they kindly let me into their lives and the families of the people who died. What did they think? Why did these people do this? Why did they go to K2? You’re right: What is it about K2 that drove them there?

Obviously you deal with very heavy subject matter, I mean, lives ended in this book. Do you fear any sort of criticism from survivors since you weren’t on the mountain?

Yeah. I’m not a mountaineer, so I had to work really hard to overcome that. Many people were really welcoming. They wanted to tell me and help me understand. I also had to work hard, but I relied a lot on their kindness and openness. I went to France to visit Hugues d’Aubarede’s family for three or four days. It was really hard to begin with and they were quite skeptical, but I had to convince them that I was a reporter and that’s what I was bringing to this story. A real independent and an outsider’s perspective that wasn’t biased — -you were right to point that out at the beginning — -who could do their story justice.

Are you concerned about experiencing a similar backlash to Krakauer?

Yeah, I hope not. I really do. There were some negative aspects in there, but I really reported it out. I spoke to everybody that I could. So I really tried to pin down the story. I had to choose a certain point of view, and I varied that through the book. When you do that, you cut out other people’s stories. That’s a problem, because there are multiple stories here. But I tried to capture the most important moments and tell the main stories.

Since you’ve written an entire book here, I’d guess you’re extremely confident that the narrative put forth is the nearest thing that happened up there. But would you still concede that there could be varying stories? That maybe you didn’t get it all right?

I think that’s entirely possible. I think I can only tell a story as good as the story told to me with my reporter’s notebook. I spoke to many people, and I discounted some of the things that people told me. I would go back and double check and triple check to try and get a democratic point of view of things. There is a big portion of the book where it is just one person, and I had to dramatize that person’s journey on the mountain. Yeah, they were affected, and I’m sure I got things wrong. All I can say is that I tried to bring the highest degree of reporting standards to it, and there were lots of things I left out when I wasn’t confident that it was right.

Evan Hilbert really likes books about sports. Do you know any good new or forthcoming books about sports? Tell us, and we will spend six minutes with their writers too!