The Defenders

by Matthew Van Meter

This story was co-published with Longreads.

On December 20, 2013, Christine Morales got up at seven to make breakfast for Kierra, her two-year-old daughter. They lived in a public housing project in Hunt’s Point in the south Bronx, where Morales worked as a security guard at a grocery store. When they were getting ready to leave, the door of the apartment exploded. Police officers burst in, carrying shields, guns drawn. One waved a search warrant; Kierra started to wail. As an officer pushed Morales to the wall and handcuffed her wrists, her mind raced: she thought through everything she had ever done wrong, trying to understand what had brought the police into her home.

Morales’s arrest instantly set in motion a chain of dispiriting events. Because Kierra was two, and the arrest was for a drug charge, the Administration of Children’s Services opened an investigation. Because Morales lived in public housing, the New York City Housing Authority began eviction proceedings. The police built a case to lock her out of her apartment under a Nuisance Abatement law. Finally, she lost her security license, so she could not go to work.

After spending the night in central booking, Morales was assigned a public defender, Seann Riley, for her arraignment at Bronx Family Court. He asked her about her case and her concerns; she said she just wanted to see her daughter again. The prosecutor read her charge aloud: possession with intent to distribute — Morales’s boyfriend had been dealing drugs out of their apartment. However, Riley pointed out that when police raided the apartment, they had been looking for her boyfriend, not her. The judge released Morales. Meanwhile, her father had taken Kierra to family court, where a lawyer from the child-protection agency insisted that she be placed in foster care for protection. Morales’s boyfriend pleaded guilty to felony drug possession, and, two weeks after her arrest, the prosecutor dropped all the charges against her.

At her family court hearing, Morales learned that Kierra would not be coming home, despite the lack of charges. The judge told her she wasn’t trustworthy, and that her boyfriend had taken the fall for her. She was allowed to see her daughter, supervised, at the child protection facility. When time came to leave, Kierra would ask why she couldn’t go home with mommy, and Morales would try to explain, trying to keep it together until she walked out the door.

Morales’s experience is common in New York, and more common still in the Bronx. Kierra was one of more than ten thousand children placed in foster care, almost all after suspicion of parental neglect — a catchall term that includes everything from excessive corporal punishment to missing doctor appointments. Morales’s poverty was her vulnerability: living in public housing subjects a resident to twenty-four-hour surveillance and automatic eviction after being charged with even low-level crimes.

When the criminal charges against her were dropped, her public defender had technically done his job. The government is required to provide a lawyer to help people through criminal court, nothing more. But Morales’s lawyer was from the Bronx Defenders, which extends representation from criminal court to family court, housing court, and court. Morales was one of 30,000 Bronx Defenders clients in 2014 — the only criminal defendants in the city or the country to receive these across-the-board services.

Even after her charges were dropped, Morales had a family attorney and a parent advocate to challenge the family court judge’s ruling. When the police locked her out of her apartment, a civil lawyer from her team got them to let her back in after a few hours. Her advocate, who is not a lawyer, helped her set up parenting classes, and a social worker checked in with her to see how she was dealing with life alone and to offer moral support. Kierra finally came home in June 2014, six months after the arrest.

On December 4, 2014, Robin Steinberg returned late to her Upper West Side home. Her gray, shoulder-length hair was frizzy with static, and her voice was hoarse from shouting “Eric Garner! Michael Brown! Shut the whole system down!” with thousands of others in the streets of Lower Manhattan. The day before, a Staten Island grand jury had failed to indict the police officer who choked Eric Garner to death. It was midnight, and she had to go to work the next day at the legal-aid firm she founded, widely considered the best in the country: the Bronx Defenders.

She was too charged-up to sleep. She pulled a beer from the fridge, sat cross-legged on her bed, and opened her laptop. More than a hundred new emails sat unread in her inbox, but one in particular stood out. It was from Joe Stepansky at the New York Daily News. “Hi Robin,” it read, “The video posted below has police unions upset. The credits say the video is sponsored by Bronx Defenders. Care to comment?” She clicked on the link, and watched a montage of depictions of police brutality. Then, she saw an image of two black men holding guns to the head of a white man in a New York Police Department uniform. She felt blood rush to her face.

A month before, a music video producer had approached a lawyer in her office to see if they wanted to help make a video about the killing of black men by the police. Uncle Murda and Maino, the rappers in the video, heard that the organization had spoken up on controversial issues and gotten involved in projects that most law firms wouldn’t associate themselves with. Steinberg said it was fine to film in the lobby, as long as the organization got to see the final video before it was released. The point-person for the project at The Bronx Defenders was Kumar Rao, an experienced attorney who was involved in the organization’s community-outreach programs; he had gone in November to Ferguson, Missouri to provide counsel to jailed protesters. When Rao read the words to the song, titled “Hands Up,” he expressed trepidation to Steinberg about some of the lyrics, and she agreed, but she said to wait until they could review the final video. That was the last she heard of it until she clicked on the link in her email. She was too stunned to hear the opening lyrics:

I spit that shit the streets got to feel,

For Mike Brown and Sean Bell a cop got to get killed.

Seventeen years ago, Steinberg had swashbuckled her way to prominence, making enemies of the police and prosecutors along the way. Now her foes had some ammunition to fire back, and she could lose her contract with the city.

The Bronx Defenders was born in 1997 from Steinberg’s belief that the public-defender system was failing the poor people it represented. In principle, public defense is simple. The Miranda warning states, “If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed to you.” Most people cannot afford an attorney, so public defenders represent about 80 percent of criminal defendants (that number is even higher in the Bronx). Depending on where you live, your public defender might be an employee of the state or the county or, as in New York, a nonprofit organization that acts as a contractor. Whomever they work for, public defenders, like all criminal-defense attorneys, have one duty: to represent your interests as forcefully and effectively as possible in criminal court. Usually, this means trying to get charges dismissed or reduced, negotiating an advantageous deal with the prosecutor, or, in very rare instances, defending you in a trial.

The quality of the lawyering among public defenders in New York City is universally understood to be very high; that wasn’t Steinberg’s concern. She saw inadequacy built into the very structure of public defense. In the nineties, she noticed that more of the clients she was defending were being arrested for pettier crimes than when she started in the eighties, and the effects of their criminal cases reached into unexpected aspects of their lives. In addition to facing the usual fines or jail time, they were being deported, denied student loans, or evicted from public housing. Many of them lost food stamps and custody of their children, and had their licenses and certifications revoked.

Steinberg focused on representing clients not only in criminal court, but also in housing court, family court, and immigration court. She created new positions for non-lawyers as community organizers and informal advocates, who could help people navigate the bureaucratic processes they might face. Some practices she adopted from other public defenders, some she invented. By the early aughts, the Bronx Defenders was the closest thing to a gold standard in public defense. Steinberg fought to make her model, which she calls “holistic defense,” bigger and broader, helping to push bail-reform legislation in New York State. Lately, she has spent a growing portion of her time training other public defenders through the Center for Holistic Defense, which she founded with a grant from the U.S. Department of Justice.

Among the dozen or so lawyers and policymakers I interviewed for this story, there was a general acknowledgement that the Bronx Defenders was “the best” or “one of the best.” Collette Tvedt, from the National Association of Criminal Defense Attorneys, told me “they do [criminal defense] they way it should be done. There should be more like them.” A group of law professors wrote in 2015 that the Bronx Defenders is “a model of how New York can lead the way in addressing the national problem of access to justice.” And lawyers have voted with their feet: among law students who want to go into public defense, the Bronx Defenders is still one of the most sought-after offices in the country. Last year, more than a thousand people applied for just thirteen openings in the criminal-defense practice.

Steinberg is small but not short. Her puffy hair seems outsized for her wiry frame, a fact accentuated by the skinny pants she favors. She’s pathologically neat. Her Upper West Side apartment is bright, modern and immaculately clean, its shelves and cabinets lined with her collection of salt and pepper shakers. Her labradoodle, Magic, doesn’t shed. She lives alone. Her children are in their twenties and her husband — David Feige, a writer and former lawyer at The Bronx Defenders — lives in Los Angeles. She is always moving, shifting positions as she sits or stands, and she speaks in associative lists, interrupting herself to offer counterpoints or emphasis.

The office is suffused with her nervous energy. The space looks more Silicon Valley than New York: bright and open and colorful, with a spacious lobby full of books and toys. There is no Californian informality; office attire is formal and crisp. The employees skew young, female, and extroverted; they tend to have their boss’s brashness and intensity. The constant bustle through communal spaces is by design; the office was built so that employees would need to cross the lobby at least a few times a day. Most public defender offices greet visitors with a receptionist ensconced in bulletproof glass. “It sends a message that we don’t want to send. It says, ‘We’re afraid of you,’” Steinberg said.

Steinberg forged The Bronx Defenders in the heat of conflict between Mayor Rudy Giuliani and the Legal Aid Society. Founded in 1876, Legal Aid is the largest and oldest provider of legal services for the poor. After the U.S. Supreme Court case Gideon v. Wainwright in 1963, state governments were required to provide lawyers to indigent defendants. In New York, public defenders work at nonprofits paid through government contracts. The Legal Aid Society won the initial contract to become New York City’s main provider of public defense in 1965.

In the 1990s, Giuliani brought in Bill Bratton as Police Commissioner and implemented “broken windows” policing on the theory that the gains in safety would trickle upward. The number of arrests in New York drastically increased, especially for minor crimes such as “theft of services” (jumping a turnstile) and catch-all infractions like “disorderly conduct.” Legal Aid represented 300,000 clients each year by the mid-nineties — an average of six hundred and fifty per lawyer per year. In 1994, management announced a wage freeze and slashed benefits for their attorneys while giving themselves a six percent raise (at the time, a Legal Aid lawyer’s starting salary was $31,000). Eleven hundred lawyers walked off the job in protest. Giuliani decried Legal Aid’s “monopoly” in the New York papers. He refused to sign a new contract with the organization unless it agreed to budget cuts. After a year of negotiations, a new contract was signed in 1995; Legal Aid laid off 16 percent of its attorneys, restructured its management, and relinquished its status as the city’s only institutional provider of legal services to the poor. Giuliani put out a call for other organizations to take on at least ten percent of the city’s criminal cases.

Steinberg saw an opportunity to build a better public defender. At the time, she was working at Neighborhood Defender Services of Harlem, a tiny, community-oriented public defender that picked up a few hundred cases a year. She had no love for Legal Aid, which she considered hidebound and bureaucratic, but she hated to see public defenders excoriated in public. She had been drawn to Neighborhood Defender Services because it provided not only representation in court, but also access to drug treatment, therapy, parenting classes, and other services that are often required by judges as part of punishment, especially for low-level crimes. To avoid competing with her employer, which was applying for a contract in Manhattan, she put in an application for the Bronx. She got it, rented a drab space in the Grand Concourse Mall, and then thought to herself, “Holy shit. Now what do I do?”

Legal Aid did not receive her well, nor did the courts in the Bronx. “The supervising judge wouldn’t talk or meet with us,” she said. “The Legal Aid lawyers were overtly hostile. I mean, you would leave your jacket on a chair and go talk with a client, and when you came back you’d find it on the floor. Things like that.” To avoid poaching talent from Legal Aid, Steinberg hired experienced lawyers from elsewhere: she took two from Philadelphia’s public defender, one from Kentucky, a private attorney from the Bronx. David Feige came with her from Neighborhood Defender Services. There were eight in all: Six lawyers, an investigator, and a social worker.

The Bronx Defenders evolved quickly in those early years, and Steinberg worked feverishly. She handled hiring and training, represented clients, went to public events. The office moved from the Grand Concourse Mall to an old ice house, and then to an abandoned restaurant on 161st Street. The pace took a toll on her. She remembered putting her infant daughter to sleep under her desk as she worked through the night. She also remembered “losing it” in a parking lot one night after an arraignment shift that ended at one o’clock in the morning.

Steinberg wanted to find a way to more fully address her clients’ needs. No one kept detailed data on the ancillary penalties — the evictions, the child removals, the deportations — that started as arrests. The range of consequences her clients faced was broader and subtler than she thought. All the civil penalties suffered by her clients were linked: losing housing or a job or custody of children made it harder for people to stay out of trouble. Steinberg was far from the first lawyer to notice this, but she was the first to create a public defender specifically designed to combat the system of collateral consequences. This system is nothing new — its roots are firmly planted in the historical doctrine of “civil death” — exiling criminals from society and stripping them of all their rights. It dates back at least to ancient Greece; in medieval Europe, exiles could be killed without fear of punishment, so complete was their separation from the community.

Civil death in America was only applied to very serious crimes, and involved a loss of voting rights, the right to enter into a contract, and the right to bring a lawsuit. With increasing concern about civil rights, the machinery of civil death was dismantled at the state level between 1950 and 1990, either repealed by legislatures or overturned by courts. By that time, the U.S. was gripped by fear of drug addiction, and Ronald Reagan re-declared the War on Drugs. Goaded by Reagan’s racially coded talk of “welfare queens,” many Americans felt indignation at a perceived sense of entitlement among the unemployed poor. Legislators, spurred by the anger of their constituents, began appending civil penalties to drug crimes. Today, the American Bar Association lists 47,521 laws that enforce collateral consequences in its database. Thirteen hundred of those are in New York State. “Civil death,” wrote Gabriel Chin, a law professor at the University of California at Davis, “has surreptitiously re-emerged.”

As “broken windows” policing took off in the nineties, the number of people rounded up for misdemeanors skyrocketed. “Police,” Steinberg said in a speech last year, “find [low-level criminal] behavior wherever they look. But where they look is only in poor communities and communities of color.” In the late nineties the ground was shifting under Steinberg’s feet. “What I learned,” she told me, “was that, in a day and age when eighty percent of people are charged with misdemeanors, an emphasis on just doing good criminal defense is misplaced. If this was 1975 and everyone was being charged with violent felonies, then maybe things would be different, but the misdemeanors burn you. Burn you.”

If the criminal-justice system evolved fast, the Bronx Defenders evolved even faster. In 1999, Steinberg brought on McGregor Smyth, a Liman fellow from Yale Law School, to develop a civil practice that would address collateral consequences. She wanted to base her civil practice on data about clients. Smyth tracked team referrals — any time a client’s case spilled beyond the confines of criminal law. In 2000, he reported on what he had learned about the collateral consequences faced by Bronx Defenders clients. The data indicated that the range of penalties was greater — and faced by more clients — than anyone knew. A high percentage of clients lived in public housing, and even more had family members in public housing. Almost all were on some form of public benefits. A full third had not been born in the United States.

Immigration was an early priority. Without representation, an immigrant has four percent chance of winning his or her case. With a lawyer, that chance increases to thirty-eight percent. If many Bronx Defenders clients feared deportation, even more risked losing custody of their children. Steinberg began a pilot program for family lawyers in 2004; it was such a success that in 2007, the Bronx Defenders received a contract from New York City to represent all parents in abuse and neglect hearings in the Bronx. Family court was a revelation to Steinberg: the procedures are looser than in criminal court, where rules were developed over hundreds of years and refined by dozens of Supreme Court decisions. Family law, by contrast, has little more than nebulous best practices to guide its work. “We wanted to bring a social-work approach to criminal court,” Steinberg told me, “but we wanted to bring lawyering to family court.”

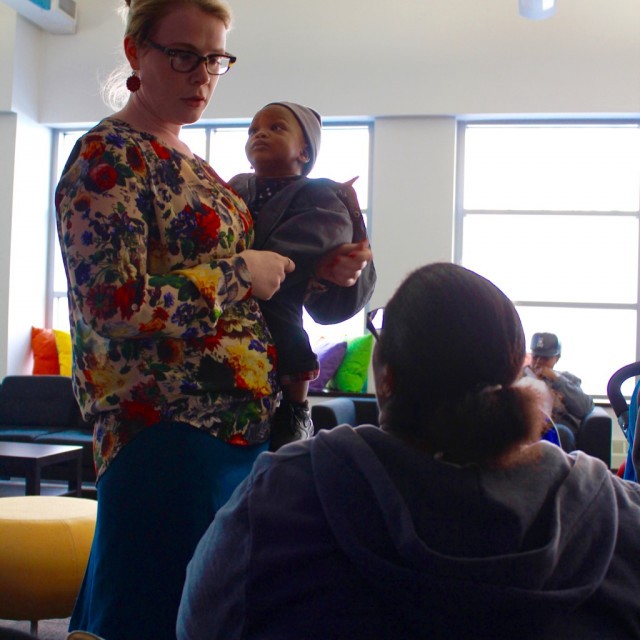

I spent eight days in Bronx Family Court over five months in 2014 and 2015, mostly following around Mary Anne Mendenhall, Supervising Attorney of the Family Defense Practice. Steinberg describes her as “a force of nature”; I ran to keep up with her as she strode from hearing to hearing while delivering a breathless overview of each client’s story. Steinberg said that a major criticism of the Bronx Defenders is that “we push too hard,” and Mendenhall could be Exhibit A. In the tiny, crowded family courtrooms, she crouched, cat-like, ready at any moment to spring to her feet with an objection. Once up, she exploded: “Your Honor, my client feels that [the child protection agency] doesn’t understand the realities of raising three kids in a shelter.” “Your Honor, my client has been in police custody since seven this morning; she is terrified.” “Your Honor, I must again object to the nature of this question!”

Immigration and family defense were joined by housing defense in 2003 and the first civil legal advocates in 2005. Civil legal advocates help clients with anything that doesn’t require a lawyer: recovering property confiscated by the police, for instance. They also do many of the tasks that would ordinarily be done by paralegals and legal assistants (positions that don’t exist at the Bronx Defenders) like taking client phone calls and preparing visual exhibits for trial.

With programs multiplying, Steinberg realized that the New York City contract money would not be enough. So she held the first annual fundraiser at Anthology Film Archives in Manhattan and “screened a very depressing black and white movie about the immigrant experience in New York City… and we had to scrub the toilets ourselves before the event,” Steinberg said. That event raised a few thousand dollars. In 2014, the gala, held at a TriBeCa event space, raised $412,000, on top of other donations that year of about $1.2 million. Compared to the $22 million provided by the government, the private gifts were small, but without them, there would be no way to fund the nontraditional positions at the Bronx Defenders.

After taking ten years to expand and develop the Bronx Defenders, Steinberg took a stab at structural reform. In 2007, she set up the Bronx Freedom Fund, the first organization of its type, to cover bail costs for some clients who couldn’t afford it. Defendants who can’t post bail in New York are sent to the notoriously tough Rikers Island, and because most of them are charged with very minor crimes, the pressure to plead guilty simply to be allowed to return home is very high. An influential story by Jennifer Gonnerman in The New Yorker in 2014 illustrated this problem: Kalief Browder was arrested for allegedly stealing a backpack, and held for three years on Rikers Island because he wanted to maintain his innocence and couldn’t post bail (he later committed suicide). Most detentions are not so long — the average jail time for misdemeanors is fifteen days in New York. Browder, who was charged with assault, would not have been eligible for the Freedom Fund, but the conundrum is a familiar one. Over 90 percent of New York defendants who cannot make bail plead guilty, usually to minor crimes, and suffer collateral consequences.

The concept of the Freedom Fund is simple: the organization posts bail of up to $2000 for defendants charged with nonviolent misdemeanors. When the defendant shows up to court, the money is returned to the fund. Defendants who can’t make bail are nine times more likely to plead guilty than those who can pay. Almost two thirds of the charges against Freedom Fund recipients have been dismissed. “We knew that!” Steinberg told me, throwing her arms wide, “We knew that! If [prosecutors] have you on some junky misdemeanor, and they think you can’t make bail, they know you’re going to plead guilty like that.” She snapped her fingers. Without the threat of jail hanging over the defendant’s head, she said, most cases aren’t strong enough to bother prosecuting.

The Bronx Freedom Fund was also the cause of Steinberg’s first big political fight. In February 2009, the Bronx District Attorney challenged the legality of the fund, arguing that a non-profit organization cannot post bail for a defendant. Steinberg had taken care to separate the Freedom Fund from the Bronx Defenders; the fund shared no board members with the Bronx Defenders, it was a separate 501(c)(3) nonprofit, it offered bail to anyone who could not afford it (not just Bronx Defenders clients), and the two organizations did not share resources. But in June, the Supreme Court of Bronx County decided that the Freedom Fund amounted to an insurance company without a license. The court rejected the District Attorney’s claim that the Freedom Fund amounted to an ethical violation, but the fund itself was dead. Steinberg was disappointed; she considered microloans and other ways to achieve the same goal. Then her husband said, “Well, why don’t you just change the law?”

Steinberg connected with Gustavo Rivera, a Democratic state senator from the Bronx, and created bill that would create a provision in to Article 68, New York State’s Insurance Law, for “Charitable Bail Organizations.” She even found a Republican backer, Phil Boyle, a from Long Island. The bill appealed to his fiscal conservatism: posting bail is immensely cheaper than incarcerating a defendant on Rikers Island, which costs taxpayers nearly $500 per day. It passed in the summer of 2012 with bipartisan support. Steinberg re-opened the Bronx Freedom Fund later that year and offered to help support more such organizations. For two years, no one was interested, but after the Browder story ran in The New Yorker in 2014, lawyers everywhere started calling for advice.

In September of 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice announced a $350,000 grant to fund the Center for Holistic Defense, the training wing of the Bronx Defenders. The Women’s Law Association at Harvard Law School selected Steinberg as an honoree for its 2015 International Women’s Day celebration. The criminal justice system was all over the news: Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, #blacklivesmatter. Suddenly, as she described in a speech last year, “after decades spent shouting into the void,” Steinberg finally had the attention of powerful people. Even the N.Y.P.D. seemed interested in how the Bronx Defenders could help: in November of 2014, Steinberg met with Susan Herman, the Deputy Commissioner for Community Policing, to discuss potential changes in police policy.

The Bronx Defenders was riding high when Steinberg returned home from protesting downtown to the controversial video. That September, James Barrett, a producer at 1st Ave Productions, asked if the organization was interested in helping to make a video that would “raise public awareness of controversial law-enforcement practices.” Kumar Rao and Ryan Napoli, experienced criminal-defense attorneys, were put in charge of the project. They agreed 1st Ave Productions could film in the office, and a few Bronx Defenders would appear in the video, but no money could change hands, and Rao and Napoli would be able to approve the video. Steinberg was excited — any chance to show off the team model, she figured, was a P.R. victory.

In November, Rao was sent a rough cut of the video without the provocative opening. It began with images of a family mourning the death of a man shot by the police. After he watched the whole thing, he went to Steinberg. “Robin,” he said, “there are some lyrics in there that we won’t want to be associated with.” In particular, he was referring to a line calling the police “cocksuckers.” Steinberg said to wait until they get a final version to go through and cut lyrics. Two weeks later, without any further communication, “Hands Up” was on YouTube, and it included almost two minutes of new footage, including the image of the rappers holding guns to a police officer’s head. By the time Steinberg saw it, the video already had 100,000 views.

Steinberg alternated between fearing for the future of the Bronx Defenders and waiting for the media to move on. During the sleepless night after she read Stepansky’s email, she tracked down someone named Eddie at Worldstar who said he had the power the edit the video. “I used my scary lawyer voice,” she told me — she convinced Eddie to remove the words “Sponsored by The Bronx Defenders.” The Bronx Defenders released a statement on December 5 that said, “the producers of the video decided to release a version of ‘Hands Up’ that we did not authorize or endorse…we regret being associated with this version of ‘Hands Up.’”

On December 12, Steinberg was leaving a meeting when she got a text message from an employee saying that “2 men with badges” were at asking for her at reception. News trucks were parked on 161st Street, accompanied by police cars with lights flashing. The men were from the New York City Department of Investigations, which looks into allegations of fraud and abuse in city government. Later that evening, Steinberg got a call from Fox News’s Greta van Susteren to be on her show. Steinberg said she could smell a trap and hung up; the segment aired without her. Van Susteren asked Ted Williams, a black former police officer who appears periodically on Fox News, about the Bronx Defenders’ appearance in the video.“There is no defense. When you lay down with fleas, you should expect fleas to get off on you,” he said. Steinberg couldn’t keep herself from reading and re-reading the news. “Public Defenders Appear In ‘Kill Cops’ Rap Video,” said the New York Post on December 13. The Washington Times announced “’Cop Got To Get Killed’ Rap Video Features Bronx Public Defenders.” Pat Lynch, president of New York’s largest police union, said, “This video goes well beyond the parameters for protected speech and constitutes a serious threat to the lives of police officers.”

A week later, on December 20, two N.Y.P.D. officers were shot and killed in Brooklyn. Ismaaiyl Brinsley, the shooter, had expressed anger at the police on social media. Three days later, Lynch sent a letter on union letterhead to Attorney General Eric Holder, linking “Hands Up” with the killings. He sent additional copies sent to the Department of Justice, the mayor’s office, and each of the Bronx Defenders’ major donors. Steinberg told me that if Brinsley, who committed suicide before he could be arrested, had been found to have watched the video, the Bronx Defenders would have been finished. Three days later, Steinberg sent a cease and desist letter to Worldstar Hip Hop, insisting that “Hands Up” be removed from YouTube. She got no response.

The D.O.I. had subpoenaed the Bronx Defenders’ records in mid-December. “Honestly, I had to look up what they do,” Steinberg told me, “and it says they do waste, fraud, and abuse. So I wasn’t worried about it: no public funds were used to make that video. No problem.” Steinberg even offered to go over the organization’s finances with the investigators. It wasn’t until she was called for an interview downtown at D.O.I. headquarters that she understood that the investigation wasn’t about fraud; it was trying to prove an ethical violation. An investigator gave her a paper with the lyrics of the song and asked if she was familiar with them. She said she knew what they were, and he told her to read them aloud to him. Glancing at his tape recorder, she said, “Yeah, I’m not going to do that.” He took the paper back and read them to her. For the first time, she told me, she feared for the future of the organization she had built and grown.

On January 29, 2015, the D.O.I. released its report to the public. It excoriated the Bronx Defenders and said that Rao and Napoli “fell short of the basic integrity and competence that the City should expect of attorneys entrusted to provide essential legal services to indigent populations paid and paid for by City tax dollars.” Mayor Bill de Blasio called the Bronx Defenders’ actions “heinous.” Rao resigned the next day; Napoli two days after that. The report blasted Steinberg’s leadership as “fundamentally deficient.” On January 31, Steinberg announced she would take 60 days’ unpaid leave. Steinberg received notice of a misconduct investigation, the first step to disbarment. Hours after the New York Post ran a story in February about Harvard honoring Steinberg, the Harvard Women’s Law Association rescinded its invitation (“Post Educates Harvard” the Post crowed the next day). On February 19, de Blasio announced that he would not approve the Bronx Defenders’ $20 million contract until the organization “improved their standing.” Steinberg retreated to her husband’s house in Los Angeles.

Steinberg grew up mostly in Manhattan with a largely absent father. When he was around, Richard Steinberg would refuse to leave bed for days at a time, or sometimes he would run up and down the apartment hallway, too excited to sleep. He drank heavily, and his addiction gave way to pills and marijuana, then cocaine and heroin. Steinberg speculates he was bipolar. His disappearances stretched from days to weeks and then months. Her parents divorced, but kept up an on-and-off romance. Steinberg told me that he nearly died many times, in circumstances that she now considers suicidal: He drove his car straight into a concrete wall, and he once perched himself on a window-ledge at the Gramercy Park Hotel.

In 1974, Steinberg’s mother announced that the family was moving to southern California. Steinberg entered her senior year of high school in Los Angeles, and the following year, she headed to Berkeley, which she had heard was the most likely place to host a revolution. Steinberg kept up her relationship with her father; she was the only one in the family to do so. She went to see him in Phoenix in 1976 — his apartment was empty, save for an aquarium full of piranhas. There was no food in the fridge, only a bunch of cocaine and heroin. A few years later, Steinberg attended N.Y.U. Law School and moved to a studio apartment in the East Village. Her father bounced from place to place in New York, until he showed up at her door one day, saying he needed a place to sleep. He slept on the floor, and he was gone when she got back from classes. Shortly after landing her first job at the Nassau County Public Defender in 1982, Steinberg got a call from her cousin. Richard’s body had been discovered at his parents’ place on 35th Street. He had overdosed on a speedball and a medicine cabinet’s worth of pills.

Steinberg resists the suggestion that her upbringing had anything to do with her career choice, that somehow her allegiance to people in tough circumstances came from her relation to such a person. She prefers to think of herself as springing fully-formed and armed, like Athena, from the campus of the University of California. But the themes of her upbringing — independence, improvisation, loyalty — run so clearly through her work that it’s hard to take her at her word. The restlessness, and the need to always be moving and changing that she inherited from her father, have defined her success and the success of the Bronx Defenders.

By late spring of 2015, the “Hands Up” scandal disappeared almost as suddenly as it had begun. De Blasio quietly announced that the Bronx Defenders would receive its contract from the city. The police union shifted its focus to other issues. The management team had worried that fewer law students would apply for jobs at the Bronx Defenders, but it received more applications that fall than ever before. On January 29, 2016, Bronx native and Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor spoke at the annual gala, where “Hands Up” went unmentioned.

Steinberg seemed almost disappointed to return to the day-to-day operations, like a soldier returned from a tour of duty: grateful not to be shot at, but missing the adrenaline. She was invited back to Harvard, not for Women’s Day, but for a newly inaugurated “Trailblazer” lecture. Her speech focused entirely on the scandal. She said the experience had connected her to her clients’ reality of being “unheard and intentionally misheard by those with power.” (“Except,” she hastened to add as she described the speech to me, “I have privilege.”) She insisted the scandal had cemented her outsider identity: “And it is from my outcast state,” she concluded, “that I intend to blaze a trail forward. Not just to Harvard, but to a world where holistic defense empowers clients, to a place where the voices of marginalized communities are amplified by collective action and to a future where we all remain committed, more than ever, to speaking truth to power on behalf of those that most need it.”

In March of 2016, Steinberg announced that the Bronx Defenders was embarking on a new project: this fall, a small group will move to Oklahoma to create and run a holistic defender for women and their children in the impoverished neighborhoods of North Tulsa. Oklahoma has an unusually large population of women in prison — the consequences of their incarceration can be devastating in terms of poverty and family stability. Steinberg sees the project’s name “Still I Rise — Tulsa,” inspired by Maya Angelou, as a throwback to her past: “it feels good to get back to my feminist roots!” she said.

Despite its near-universal acclaim, the Bronx Defenders is a one-off. The holistic-defense revolution has not happened, at least not in the wholesale way the Steinberg envisioned it. Few institutions are slower to adapt than law firms, and holistic defense may not be as sought after as Steinberg thought. If that thought enters Steinberg’s mind, she never expresses it. She has a vision of radical, nationwide change, but the main obstacle to her success in that aim may be herself. Though she insists loudly that “holistic defense is replicable, it is universal, and it is scalable,” one gets the sense that all the offices paying for trainings and assistance are not buying holistic defense; they are buying Robin Steinberg. Whether the Bronx Defenders can keep adapting, and whether it can maintain its position as the best public defender in the country without the close guidance of its founder and leader will be the best indication of the long-term success of holistic defense.

On a cold November day, Steinberg scheduled an early-morning breakfast meeting with a lawyer for American Express. She is grumpy in the mornings, and she doesn’t like talking shop that early. But this corporate contact offered power and connections, and he was willing to meet her on the Upper West Side. “Oh, fine!” she told her assistant. Seann Riley, Deputy Director of The Bronx Defenders, looked over at Steinberg and said, “What do I always say to you?” “I know, I know!” she said and flung her arms wide. “I’m a whore for justice!”

This story was co-published and funded by Longreads. Sign up to get their free newsletter, delivered every Friday for your weekend reading pleasure.