Shutter Madness

by Jacob Mikanowski

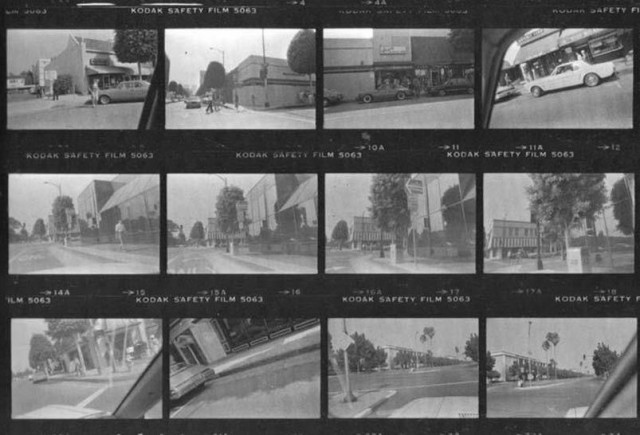

Garry Winogrand, proof sheet from 1982 or 1983

Garry Winogrand used to say that he took photographs of things to see what they would look like as photographs. He took a lot of them. He photographed relentlessly: crowds, zoos, dogs, cars, parties, sidewalks, train stations and women, always more women. He’d describe a good night as “thirty-five rolls.” A good year might involve a thousand. He was always slow about editing. He had a rule that he wouldn’t even look at an exposure for a year, so that emotion wouldn’t cloud his judgment, but towards the end of his life he wasn’t even doing that anymore. He just let his rolls pile up in trash cans and in the fridge.

When he died, of gallbladder cancer in 1984, he left behind more than half a million exposures. Most of them were unedited. Most of them he had never even looked at. Winogrand had always been prolific — but this was something else: three hundred thousand pictures (at a minimum), barely sorted, unorganized, with no indication of why or when they were taken. By most counts their quality didn’t keep up with their quantity. Thousands were botched, “plagued with technical failures — optical, chemical, and physical flaws — in one hundred permutations.” The ones that weren’t tended to be either banal or badly composed, but there were so many of them it was hard to get a read on the whole.

The archive Winogrand left behind was an ocean — trackless, infinite, and unsurveyable — and few had the patience to enter into it. Contemplating its immensity, the curator Alex Sweetman imagined a photographic blob, oozing out of its drawers until it blocked traffic on the entire East Side. Leo Rubinfien, the curator of a new retrospective predicated on the idea that the late work wasn’t all bad, admits to a severe drop off in quality. And even John Szarkowski, Winogrand’s close friend and chief patron, while editing the late work for a posthumous exhibit, found himself feeling first impatient, then angry, and finally convinced that he was the butt of a cruel joke, “designed by the photographer to humiliate him.”

Winogrand’s late work was a failure. Not only that, it was a failure so grand and ambitious, so vast in its scope and comprehensive in its extent, that it immediately turned into a cautionary tale. What could better embody the seductive ease and terrible difficulty of photography than those three hundred thousand aimless, shambolic pictures? They’re a fiasco, a warning and a monument, the medium’s Gallipoli and its Xanadu. They combine everything I like in art: obsession, risk, ambition, disaster. Failure can be more interesting than success — and more revealing. I want to know what happened to Winogrand in those final years. What did he think he was doing? Did his talent desert him, or did he stop trusting it? Was he looking for something else entirely, something beyond art or reason? Or is there something peculiar about photography, particularly the kind of photography that makes its practitioners prone to obsession and repetition?

Garry Winogrand.

Save for later with Pocket.

Garry Winogrand was born in the Bronx in 1928. New York was his native ground and the street was his element; it’s where he got his energy and trained his eye. He started taking photographs when he was twenty, after a brief tour in the army and an even briefer stint as a painter. Painting bored him; it was too fussy and too slow. A friend told him that there was a darkroom he could use at Columbia, anytime he wanted, and that was that.

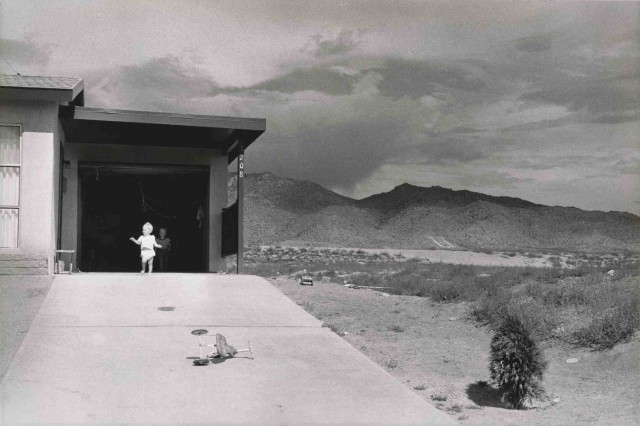

It took Winogrand a while to hit his stride. Throughout the fifties he made photographs that were technically strong, but not too original. He took pictures of window shoppers and bums, bathers at Coney Island and party girls at the El Morocco Club. A lot of them hark back to the work of the Photo League from the 1940s. Some look like Ruth Orkin or Dan Weiner, others contain a touch of Henri Cartier-Bresson or a dash of Weegee. Sometimes though, he’d find his way to something new. On a road trip through the southwest in 1957, he took this picture of a baby emerging into the desert out of a dark garage. For a second it seems as if all of America is living in a bomb shelter while atomic light pulverizes the ground outside.

Garry Winogrand, “Albuquerque,” 1957; gelatin silver print; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, purchase; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Garry Winogrand, curated by Leo Rubinfien with Erin O’Toole and Sarah Greenough, will travel throughout 2014 and 2015.

• National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., March 2 through June 8, 2014.

• The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, June 27 through September 21, 2014.

• The Jeu de Paume, Paris, October 14, 2014 through January 25, 2015.

• Fundacion MAPFRE, Madrid, March 3 through May 10, 2015.

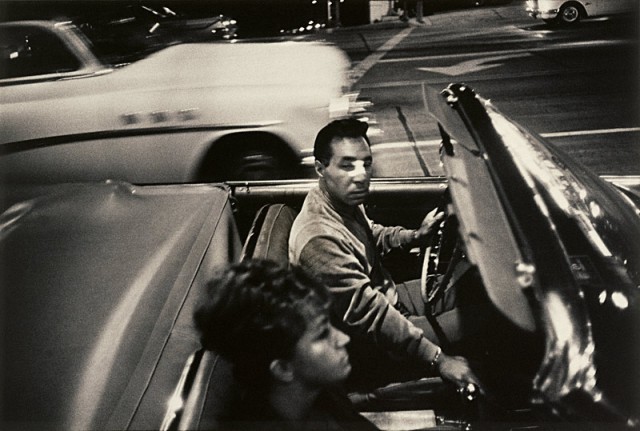

Sun, suburbia and nuclear dread: Winogrand had the 1960s nailed three years early. The bomb haunted him. He told his friends that the Cuban Missile Crisis was a crucial moment in his life. It made him lose faith in politics, and democracy. When he was applying for a Guggenheim grant, he wrote then when he looked at the pictures he had done up to then, he felt “that who we are and how we feel and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter… the bomb may finish the job permanently,” but despite his concerns, he never embraced straight documentary photography. When Robert Frank published The Americans in 1958, he forever cemented a certain moody fifties look, of glowing jukeboxes, lonely highways and small-town drive-ins lit up against the night. But the book also made it clear that a photograph didn’t have to be an impersonal document. Just as Walker Evans had earlier revealed to Winogrand that photography didn’t just record the world, but reveal it, Frank taught him that style could express subjectivity — and he spent the next decade developing one of his own.

So what makes a Winogrand a Winogrand? He had a couple of stylistic tics — wide angle lenses, tilted perspectives, bright contrasts, massed compositions — but it’s easier to define him by what he didn’t do than by what he did. Unlike a lot of great photographers, he didn’t stake out a territory and call it his own. He wasn’t interested in the decisive moment; he’d grab odd juxtapositions as they came along. He stayed in the street or in his car and photographed what he saw. Unlike Diane Arbus, he didn’t insinuate himself into the lives of his subjects. Unlike Lee Friedlander, he didn’t diffuse the tension in his pictures by making himself a character in them. He didn’t have Evans’ or Atget’s gift for making inanimate objects preternaturally solid, more real than real.

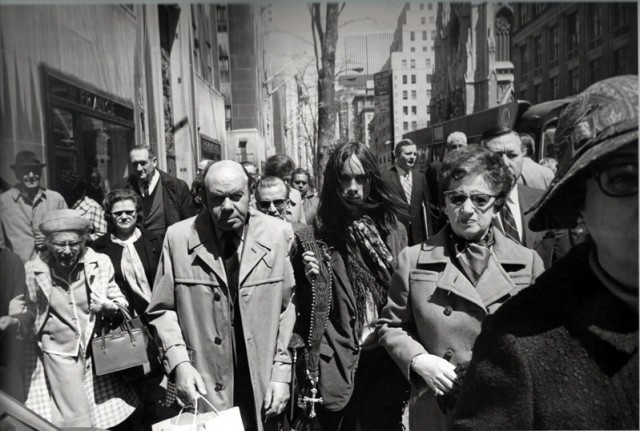

Garry Winogrand, “New York,” 1969; gelatin silver print; Collection SFMOMA, gift of Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

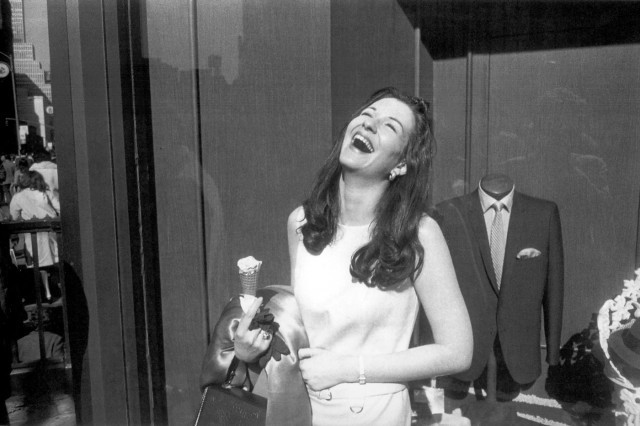

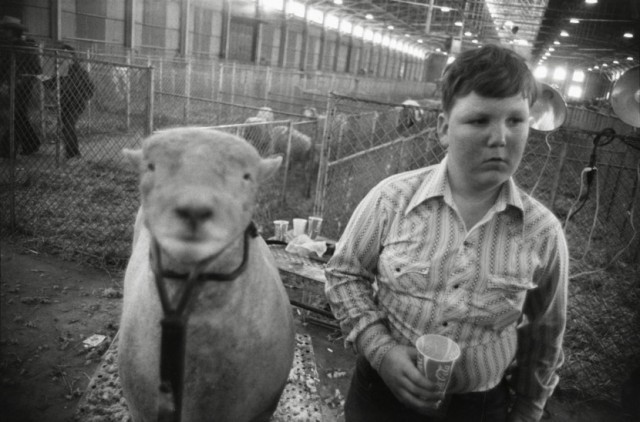

Maybe it helps to think of the movies. If Henri-Cartier Bresson was the Frank Capra of photography, always looking for the point of sentimental release, and Diane Arbus was its Alfred Hitchcock, upping its quotient of creepy-pleasurable voyeurism — then think of Winogrand as photography’s Billy Wilder. Bittersweet comedy was his thing. He was the guy you called to do Sunset Boulevard or The Apartment, to walk the knife edge between funny-silly and funny-sad, to capture the loneliness of brightly lit spaces and to get sexy laughter and situational tragedy into the same frame. He worked by inserting himself into dynamic situations — a crowd, a convention, an airport or a rodeo — and waiting for something develop. He liked cars, dogs and breasts. He was interested in angles and the limits of the picture frame. He liked to fill the whole canvas, and make the corners as interesting as the center. He makes ease look difficult. His pictures often seem offhand and dry in a way that can make it hard to know why you’re looking at them. They all seem so casual, until at some point, they suddenly don’t.

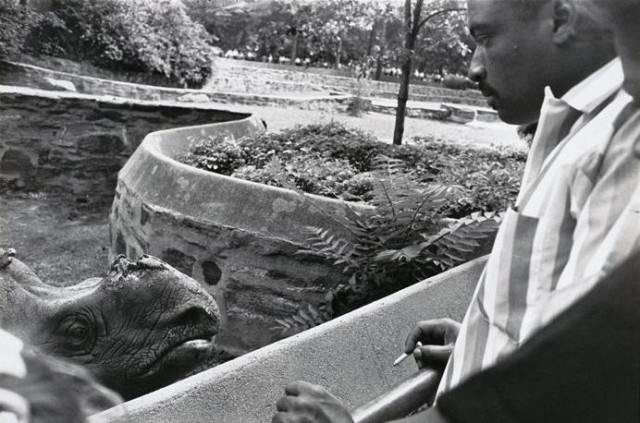

Garry Winogrand, “Bronx Zoo, New York,” 1963, Collection SFMOMA, Gift of Carla Emil and Rich Silverstein; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

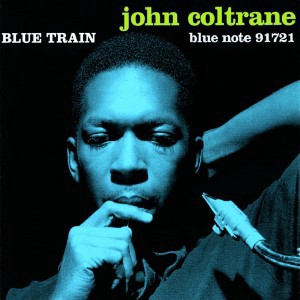

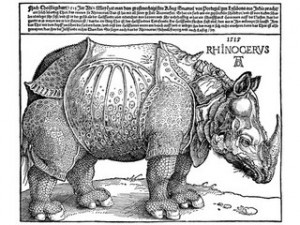

Take this picture, from Winogrand’s book The Animals. Nothing to it: just a man looking at a rhinoceros. But I love it. I like the hard quizzical look the two of them are giving each other. I like the way the man is holding his cigarette. It reminds me of the picture of John Coltrane on the cover of Blue Train, the way he covered his mouth with his hand, the very image of contemplative cool. I like the way the man’s cigarette stub echoes the rhino’s worn-down horn, like they’d both spent the day smoking, the one a cigarette and the other his life.

I like the classical composition, the big diagonal of the railing and the S of the barrier, and the way Winogrand messes with it, by keeping all the action in the corners. I like that the rhino reaches back to Dürer’s woodcut of the same. I like the way Winogrand makes the Renaissance ping pong off of fifties’ jazz and that he makes it look so easy you think you could do it yourself. I like that it makes me think of thick skins, and of armor plating and of what it takes to live in the city. I like that it makes me think about what it’s like to be an animal in a cage.

Left: John Coltrane, 1957. Right: Albrecht Dürer, 1515.

The sixties were Winogrand’s days of wine and roses. He started getting gallery shows, good ones. He quit his job as a commercial photographer and devoted himself to art. He started teaching, informally, out of his apartment. He divorced his first wife, a dancer (he had a thing for dancers) and married his second, a copywriter. He won the Guggenheim, twice. In 1967 Szarkowski included him in the seminal “New Documents” show at MoMa, along with Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander. Later, Szarkowski called him the “central photographer of his generation,” and even if not everyone agreed, his reputation as one of the leading art photographers in America was assured. He was riding high.

7. Garry Winogrand, “New York,” 1968; SFMOMA, gift of Dr. L.F. Peede, Jr.; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Ten years later it was all starting to slip away. Winogrand had books in print, he was teaching in universities, but the work wasn’t coming easily any more. He moved away from New York, first to Chicago and then to L.A. Tendencies that had kept at bay throughout his career started to get worse. Winogrand was always bad about editing his own work. He used to have a rule about not developing his rolls for at least a year after he took them, so that he wouldn’t be swayed by emotion when choosing the best ones — but now he was letting them pile up for years at a time. Winogrand had never been very interested in assembling books. He only ever put one together himself, 1975’s Women are Beautiful, which was widely dismissed. (It’s still under something of a critical cloud today — possibly because it’s a horny, masterpiece of sidewalk voyeurism taken at the apex of the age before bras). All the rest — The Animals, Public Relations, Stock Photographs (they’re of a rodeo) — were the work of his friends.

Garry Winogrand, “Fort Worth, Texas,” 1975; Collection SFMOMA, gift of Dr. Paul Getz; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Without and end goal, and away from New York, Winogrand’s work seemed to lose focus. In his last years he had his printer, Tom Consilvio, drive him around Los Angeles visiting the same locations over and over — the Farmers’ Market, Hollywood Boulevard, Grauman’s Chinese Theater, Muscle Beach — while taking pictures out of the passenger side window. He rarely left the car, and seldom got close enough to people to make their faces clearly visible. To John Szarkowski, the photos from this time look like attempts at solving a photographic problem of finding “the greatest distance” at which a figure “could be convincingly described,” but to an outsider they just look weak: hundreds of shots of curbs, parked cars, street corners, babies in strollers, traffic at intersections piled on top of each other almost at random. By the end, Winogrand wasn’t even bothering to focus or keep his camera steady at the moment of exposure. He just clicked away, playing the world like a slot machine and losing every time.

A number of theories have been floated for Winogrand’s decline. Personal problems may have been involved. By 1980 Winogrand was on his third marriage, and deeply grieved his lack of contact with the children from his first marriage. He was also sick, with a seriously broken leg and thyroid problems, both of which required surgery and long courses of painkillers. Szarkowski thought it was caused in part by new equipment. In 1982, Winogrand bought a motor-driven Leica, which made it even easier to take multiple photos without hesitation or thought. Some people blame it on Los Angeles itself: it was too big, too bright, too sprawling, too centered on the automobile to work for a true street photographer. Others blame a crisis in street photography itself. The form was saturated: at some point, the theory goes, everything you could photograph out and around — every situation, every ironic pairing of high and low, beautiful and ugly, banal and unexpected — had been captured, leaving nowhere else to go.

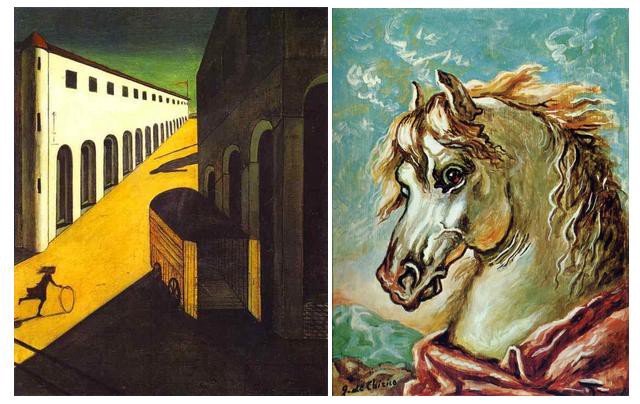

Or maybe the spirit simply left him. Talent is fickle: it comes and it goes. Rimbaud did all his writing in his teens. By age twenty he had settled into a life of aggressive, captivating silence. Giorgio De Chirico did all his best work in his twenties. Later in life, he switched from the metaphysical cityscapes that made him famous to a series of cape-wearing horses gamboling on beaches and another of sensuous gladiators — paintings so horrible that by the end of his life he was reduced to forging and back-dating his own work.

Left: Giorgio de Chirico, “Melancholy and Mystery of a Street,” 1914. Right: Giorgio de Chirico, “White horse’s head with mane in the wind,” date unknown.

Bob Dylan, by his own admission, lost it for twenty years, from the mid-70s to the 90s. He describes what it felt like in Chronicles: “The mirror had swung around and I could see the future — an old actor fumbling in garbage cans outside the theater of past triumphs… It was like carrying a package of heavy rotting meat.”

In his heyday, Winogrand was like an athlete. He didn’t have a program or theory about photography, or a set of interlocking interests. He relied on his reflexes and his skill at making aesthetic decisions in split-second increments. By virtue of its nature, his art also relied on chance. He didn’t stage or predetermine anything. I met someone recently who took a class with Winogrand in the seventies. She said he used to tell his students to take as many pictures as they could, to “increase your odds.” When he was asked how much of a role accident played in his work, Winogrand replied “99%” — and at some point, his luck just ran out.

Garry Winogrand, contact sheet, 1961

But if Winogrand felt the diminution in his work, he didn’t let it slow him down. He kept right on taking pictures, looking for the thrill, trying to find his way back to the physical sensation of making art and forgetting about the results. This is something that happens to photographers sometimes. Photographs are so easy to make and so hard to make well, that there is always a temptation to make work blindly, letting the work expand towards infinity in the hopes that something will turn up. It’s a kind of obsession, or a compulsion. Call it shutter madness.

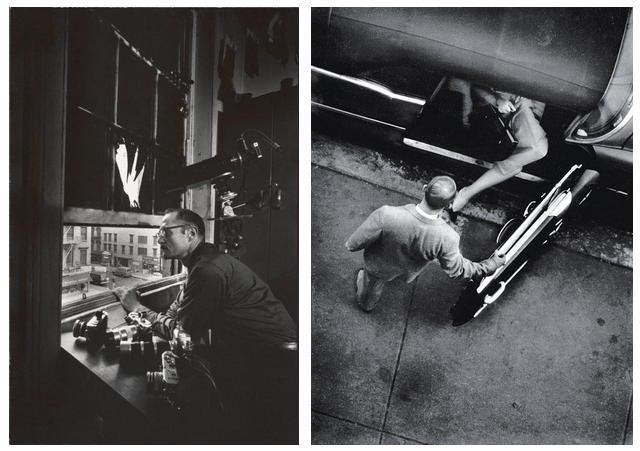

In the 1940s and 50s, W. Eugene Smith was the leading photojournalist in America. He was a star photographer for Life, then in its heyday. His photographs from Okinawa and Iwo Jima, taken when he was just twenty-six, helped define what the Pacific Theater looked like for a generation of Americans. He was best known for his painstakingly realized, graphically brilliant photo-essays on topics like life in a Spanish Village, Albert Schweitzer’s leprosy clinic, a day in the life of an African American midwife in the Deep South. Then, in 1955, he quit and went to work for Magnum. His first assignment was a story on Pittsburgh. It was one chapter in a bigger book, and it was supposed to take three weeks. It ended up taking three years. Smith would wander around the city for forty-eight hours at a time, high on Benzedrine, photographing everything that came in his path. Smith wanted to capture every facet of the city, and incorporate them into a massive book which would be his “critique of the world,” lavishly illustrated with over 2,000 glossy photographs. Naturally, his editors balked.

W. Eugene Smith.

Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona and © the heirs of W. Eugene Smith.

Smith didn’t take the news well. He left his family and moved into a dilapidated loft on Sixth Avenue, near 28th street. He called it his last stand. He imagined was an outlaw holed up in one “of the gunned fortress of old,” and pointed cameras out the windows to document everything that happened outside. When he found out that the space below his was used as a practice studio by jazz musicians, he started photographing them too. Then he drilled holes in his floor to record the audio as well. He spent eight years like this, with six cameras in his hands and a floor full of tape recorders at his feet. It was all going to be a part of the same project, his Great Book, the photographic answer to Joyce’s Ulysses. All he published was an eight-page spread with the coma-inducing title Drama Beneath a City Window. (Smith eventually donated all his photographs and recording to the Center for Contemporary Photography at the University of Arizona in Tucson, which also houses the Winogrand Archive. The combined weight of material they received was over 44,000 pounds. Some of it was published recently in The Jazz Loft Project, edited by Sam Stephenson, whose biography of Smith, fifteen years in the making, promises to be a masterpiece of the genre.)

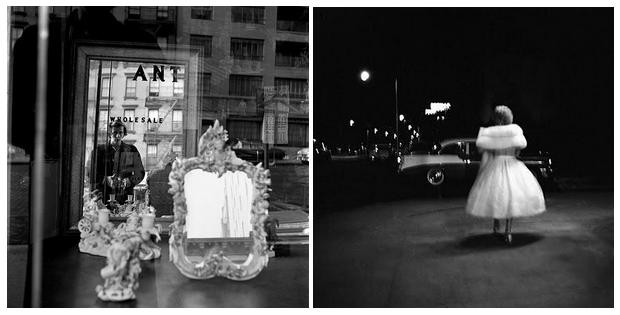

Smith’s problem was a kind of artistic grandiosity — every project he undertook was going to be the project, the culmination of his life’s work, the fullest realization of photojournalism as an art — which made it impossible to finish anything he started. Vivian Maier’s difficulty was the opposite: she was infected with a modesty that left her content to work a whole lifetime, at an extraordinary level, without exposure or praise. Maier worked as a nanny for over forty years, first in Manhattan and then on the North Side of Chicago. Over that time, she took thousands of photographs, developing over time into a prolific and technically adept street photographer. Her work is lucid, compassionate and direct. Her style has traces of Helen Levitt, some Robert Doisneau, and a lot of Lisette Model, but is exquisitely its own.

Left: Vivian Maier, “Self-Portrait,” 1953. Right: Vivian Maier, “Florida,” 1957.

No one knew about Maier’s work until 2006, when a real estate agent named John Maloof bought 30,000 of her negatives from an auction house which had previously acquired them from a storage locker she had defaulted on. He subsequently acquired many thousands more, but by the time he figured out her name and tracked her down she had died, at age 83, from a fall on the ice. She left behind over a hundred thousand negatives, but most of those were undeveloped. Her career is a kind of puzzle of artistic epistemology. She must have known she was good; why else would she have kept at it for so long, and with such determination? But at the same time she couldn’t have known how good she was, and she doesn’t seem to have needed anyone else to know either.

Vivian Maier never seems to have told anyone why she took photographs, or what she hoped to do with them. Winogrand was similar in this respect: he didn’t write much, didn’t like to explain his work or put forward any theories about its making. His reticence left a lot of people thinking that he was a kind of poet maudite, a primitive who made art unconsciously or on instinct. To John Szarkowski he was a “New York hick,” making the most of his extraordinary intelligence… and modest learning.” For Tod Papageorge, a photographer and poet who was the closest thing Winogrand had to a disciple, he was like a Buddhist monk or a Zen master, making work automatically and without ego. To Leo Rubinfien, Winogrand was just a “tradesman,” who needed Papageorge’s insight to reveal the “gravity” of what he himself was doing.

But if you listen to what Winogrand actually said about his work, it becomes clear that he did have an idea of what he was doing. It’s true that in lectures and speeches Winogrand could be maddeningly obscure. If someone asked him what he was trying to express with his photographs, he’d say that he was only trying to learn about photography, and if they asked what made a photograph interesting, he’d say the same thing: “If I can learn in a photograph something about photography, that’s what makes it interesting. Don’t ask me what that is precisely.” He was putting the audience off, but he was also expressing a truth about himself.

To Winogrand, still photography was “tantamount to driving a nail in with a saw, when you can use a hammer.” But however clumsy, it was a medium of its own, with its own propositions and ethics, and he wanted to pursue those as far as he could. He wasn’t ultimately interested in subjects or concepts — in women, or cars, or animals, the 60s, the nuclear age, the falseness of postwar life — he was only interested in how things worked in the frame. He was in love with the uncertainty inherent in the process, still amazed that “when you put a piece of paper in a tray with solution in it, it comes up.” He wanted to make photographs that said something about photography, about its essence. In short, he was a purist, a paparazzo of nothing, and that’s a hell of a dangerous thing to be.

Garry Winogrand, “Los Angeles,” 1964; Collection SFMOMA, gift of Jeffrey Fraenkel; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

I think that it’s possible that those 300,000 photographs Winogrand left behind have been misunderstood. I think that they weren’t a product of his talent dropping off, but instead they were part of an attempt to test the limits of street photography, to see whether he could make his work to be as mundane, random, and accidental as possible and still come out with something worth looking at. Taken this way, those last photographs are as potent and troubling as anything Winogrand ever did. They remind me of a Balzac story called “The Unknown Masterpiece.” It’s about three painters in 17th-century France. Two artists, a young upstart and an old pro, visit to the workshop of a master named Frenhofer. He’s obsessed with the theoretical possibilities of painting, with its ability to imitate living flesh and the tension between color and line. He’s been working on a single painting for years. They think it must be a masterpiece. Frenhofer assures them that it’s the most perfect representation of a women ever made. But when they get there, all they see is a single, perfectly realized foot. Everything else is obscured by masses of cloud-like color. In his quest to find the essence of painting, Frenhofer dissolved all of its rules, losing himself in a freedom he could no longer master.

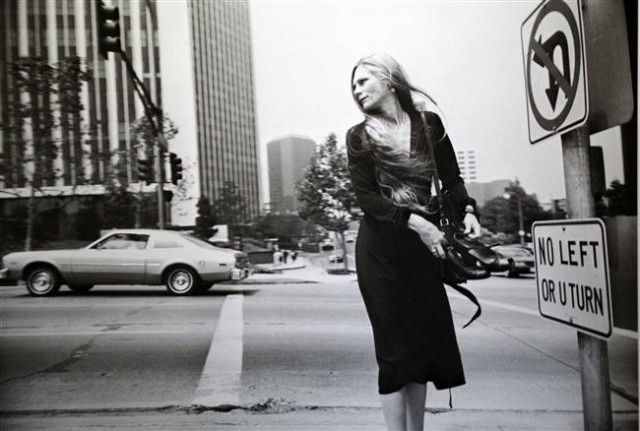

In amongst Winogrand’s late work there’s one series (or at least it looks like a series in retrospect) from L.A that’s especially haunting. It’s made up of a number of photographs of lone figures standing in the crosswalks. They look forlorn, ravaged, and determined, like they’re heading forward with no idea of where they’ll wind up. This spring’s Winogrand retrospective at SFMOMA uses these pictures to make the case that Winogrand never really lost it, that he kept making great pictures right up to the end — just not as frequently, or in a way that he recognized himself. They’ve developed a considerable number of never-before-seen works to make their case. But if it were up to me, I would have shown some of the bad ones instead — the meaningless shots of curbs and traffic lights, the blurry streetscapes, the stumbling, crooked random shots of faces in the crowd — hundreds of them, whole floors at a time. That way those last few good ones would really pop, sitting out there alone in all their poignant randomness like a beautiful foot, coalescing out of the fog.

Garry Winogrand, “Los Angeles,” ca.1980–83; Garry Winogrand Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; © The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Jacob Mikanowski writes about art, books and Europe east of Berlin.