We Have The Fakes And We're Voting Yes

by Joe Berkowitz

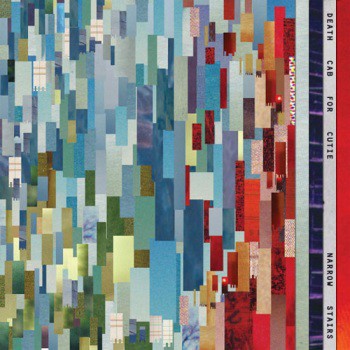

Death Cab for Cutie’s sixth LP, Narrow Stairs, inadvertently changed the way I think about music. For 16 months, I played it often and recommended it to at least a dozen people. In ranking my favorite albums of 2008, this one would sit comfortably in the top ten. That’s why it was kind of a surprise to recently discover that I’d never actually heard it before.

In April of 2008, a blogger named Charlatantric played a joke on file-sharers: his widely disseminated upload of Narrow Stairs was a fake. This version starts with a short instrumental track leading into the actual Death Cab single, “I Will Possess Your Heart”. Everything that follows, however, is the work of a German band called Velveteen. For the last 16 months I’d been listening to Velveteen’s album, all the while telling friends about “the evolutionary leap” Death Cab for Cutie had taken between albums. Like a total jackass.

The prank is old news by now. Most people who initially downloaded the fake version have long since realized their mistake. Not everyone, though, apparently. It is doubtful that the blogger responsible for the fugazi I’ve had in my iPod since December of 2008 intended to dupe people for the long-term. However, the fact that he was able to do just that, and do it so convincingly, says a lot about how we engage with music now.

When we hear a band’s new material we are listening for the reassuring signs of a familiar brand. Successful musicians today must be brands, and Death Cab for Cutie is no exception. Lead singer Ben Gibbard has the kind of soft, striking voice you can pick out of a lineup. Guitarist Chris Walla moonlights as the band’s producer, controlling their sound with a crisp, polished tunefulness. While the tone of their early output favored melancholia, by 2008 Death Cab managed to escape the dreaded emo label. They sounded like pros, and they were-having successfully transitioned to Atlantic Records, their brand became Major Label Indie.

Not only does Velveteen have the same Major Label Indie sheen, the lead singer bears a more-than-passing vocal resemblance to Ben Gibbard. Although I wasn’t impressed with what I thought was Narrow Stairs immediately, after half a dozen spins I was hooked. Yes, the fake Death Cab is a grower. Some songs have the expansiveness, attention to detail, and hummability that are hallmarks of the real band, and the emotional undercurrent of the whole affair-an equal mix of yearning and loss-fits in nicely with their discography. There was never a doubt in my mind that I was listening to the new Death Cab for Cutie record.

Of course, some red flags did go overlooked. For instance, none of the songs on the fake album actually mention their titles in the songs. This detail seemed odd, yes, but nothing to get hung up on. Perhaps the band was just being mysterious. It makes so much more sense, though, when the song, “Your New Twin Size Bed” begins with the line: “You look so defeated, lying there in your new twin size bed.”

Also, while the music on the fake album is sophisticated, the lyrics are not. A mention of “boyfriends with motorbikes,” seems uncharacteristically rooted in bygone notions of high school hierarchy. An extended metaphor built around selling a house has the distinction of being both under-sketched and overwrought at the same time. And some of the lyrics are just way too abstract and, well, terrible (e.g. “Twisted mind. Sedated, neutralized. So won’t you turn and buy me shots, and gently tending aisles.”) Let’s face it, the signs were there.

So why didn’t I notice? The authenticity of the music was never in question because there was at least one real single on it and the rest of the album hit all major points on The Death Cab For Cutie Sound checklist. Perhaps it was the way I listened to it-frequently, through headphones, but never analytically. There was never that vital feeling of needing repeated listenings so as to kind of dissect it. Also, the ease with which I procured this album took away from its eventness. Digital culture has robbed us of the inclination to run out and buy an album the day it comes out, like I did in 1996 upon the release of Tool’s Aenema. Which brings me to the main reason I didn’t notice that this album was a fake: I hadn’t actually paid for it.

All I could think about after finally buying Narrow Stairs (after discovering the prank) was why hadn’t I already bought it? This album I’d been listening to for 16 months had met all my brand expectations and proved its staying power-obviously the right thing to do was to buy it much sooner. The question is, then, what makes an album buyable in 2010? If we can illegally download all the music we want for free, and the law of averages says we will not be caught, what reason is there to stop us?

There’s morality, for one; musicians have to eat, and it’s wrong to deny them money when we obviously appreciate their work. Ownership is another reason-it’s nice to feel as though you truly possess this thing you so deeply enjoy. Also, once you own an album, you have objective social proof of fandom-you clearly feel aligned with a band’s brand enough to have shelled out money. Finally, making a purchase means you definitely won’t unwittingly download, say, Velveteen’s latest release instead of Death Cab for Cutie’s.

Each of these points has a counter argument, though. If the payoff for buying music is contributing to the band’s finances, you can justify your non-purchase of the album by paying to see the band in concert. In terms of ownership, the phasing out of CDs affects how we define the concept. Simply having the songs in digital form feels so ephemeral compared to having something you can hold in your hands and stow in your apartment forever. Social proof isn’t the same anymore either. Illegal downloading has made it far too easy for anyone to gain whole discographies in the blink of an eye-actually having an album doesn’t carry the cachet it once did. Unbelievably, it now seems that actually having the right album might not even be enough incentive to pay either.

We consume new music by weighing the finished product against our expectations of it, and forming a position. What we don’t like we discard; what we do like we listen to frequently, forestalling the inevitable cycle of overplayed obsolescence and occasional resurgence. Digital culture is ultimately disposable. That’s why it makes sense that it could be anonymous too. The Velveteen album served the same purpose and produced the same effect for me as the Death Cab for Cutie album it replaced for 16 months. In doing so, it proved that as long as our expectations are met, we’ll believe anything, even if we don’t buy it.

Joe Berkowitz is an assistant editor and freelance writer living in New York City. His chi can be channeled here, and also here.