The Census: "What Is Person 1's Race"?

When my German-American mother married my black-American Indian father, her dad and stepmom disowned her immediately. They would have been upset had she married an Irishman — “Those people kiss the filthy Blarney Stone,” my grandfather would say — but a dark man was practically incomprehensible, like marrying an ironing board. “Race-mixing,” as my grandfather called it, was an abomination.

The last thing my mom remembers her dad saying as she walked out of his modest Akron home is, “I never want you in our lives again.”

Because she is a deeply kind, God-fearing woman, a couple weeks later, at Christmas, my mother went shopping for gifts for the parents who had abandoned her. She wrapped them neatly and asked her sister, her best friend, to bring them to their parents. A few days later, my mother returned home to a patio filled with the gifts she’d sent, still wrapped. Attached to the bundle was a note: “When I said never, I meant never.”

When I think of my mother, I can’t help but think of the head-spinning ignorance she endured to marry my dad and have me, from the familial isolation to the sidelong glances to the post-divorce date that ended when her suitor saw my picture and said, “You didn’t tell me you were married to a black.”

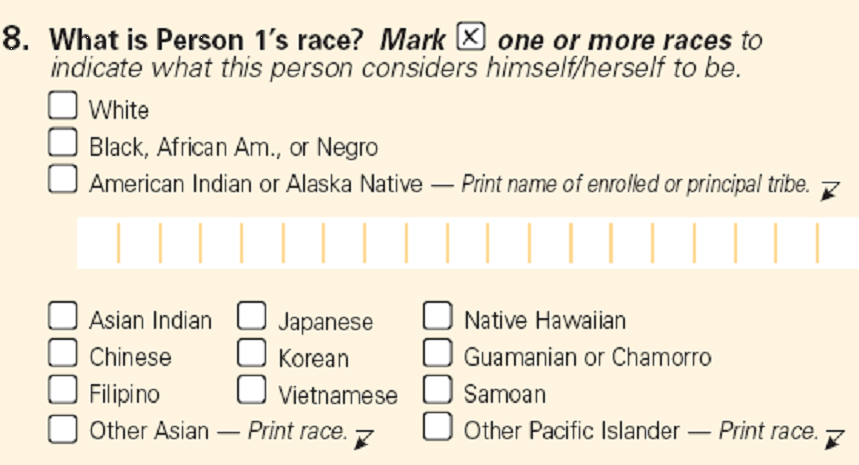

And so it went that I thought of all these things when I filled out my census form, staring at the sentence “Mark one or more boxes.”

Though what certain people perceive me to be varies depending on where I am in the world — in New York, it’s Puerto Rican; Miami, Cuban; Europe, Spanish — if a few dozen Americans saw me robbing a bank, I’m fairly certain most of them would describe me to the police as a “black guy.” Like a parolee who returns to crime when nobody will hire him, as a teenager looking for an identity, I decided it was simplest to become what people thought I was. I made certain my “blackness” was to the fore of my personality, joining the black student’s union, wearing Fubu religiously, hiding my Jawbreaker CDs from friends and wearing my Yankees hats cockeyed, a la my hero, Method Man. But by 17, I realized, as many people do, that I didn’t have a sense of being, I had a costume — a dope one, complete with lots of fresh kicks and ill music, but a costume nonetheless.

It was around then that I began to wonder what my mom had thought of my Afrocentrism. Undoubtedly, the crucible in which she forged much of her adult life was one of inhuman (or perhaps very human) rejection, most of which she took because a wellspring of love for my father and me compelled her to do so. And yet there I had been, checking off the “African American” box at the doctor’s office while she paid the bill and stroked my feverish head with her white hand. Remembering times like those, I’d never felt more mean and aloof. Most teenagers tell their parents they can’t understand them because they’re uncool or too old; I told my mom she couldn’t understand me because I was only from her, not of her.

Unlike Glenn Beck et al., I like the census. I don’t necessarily pore over the information it ultimately provides — though that’s important, I know. Instead, I like the fact that it forces us, in the solitude of our homes, to confront questions we would probably be content to constantly ignore otherwise: Who am I (which sounds corny but really isn’t)? Where do I come from? How do I want the world to know me?

I can understand why Barack Obama checked only “Black, African Am., or Negro” on his census form, leaving the “White” box blank entirely. It’s something I would have done myself at one time — and I never even had to worry about political backlash, which John Judis discusses nicely at The New Republic.

Nevertheless, I couldn’t do the same.

In a way, though it means he doesn’t really identify with me, I’m glad Obama has a desire to be seen as the first black president of the United States. But I can’t help but wonder if my grandfather, who died certain the races should never combine, wouldn’t have wanted it that way.

Cord Jefferson is a writer-editor living in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in National Geographic, GOOD, The Root and on MTV.