A Natural History Of Walter Rothschild

by Jacob Mikanowski

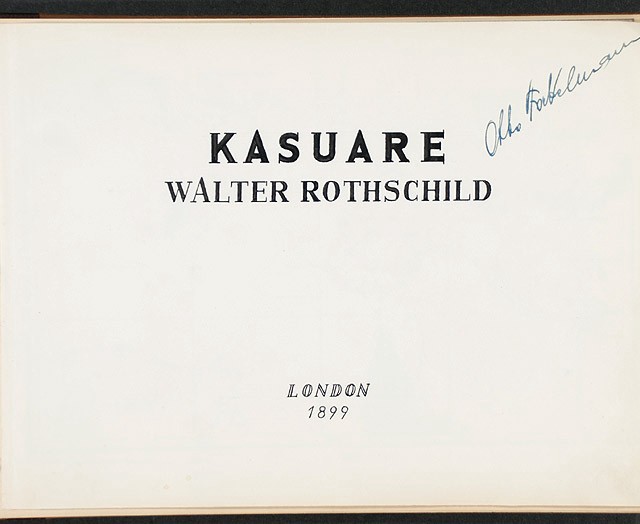

Photo: Flickr

Some men shoot tigers. Some men love bears. Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild, Major in the Yeomanry, Conservative MP for Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire, heir to one of the greatest banking fortunes in history, and collector of the largest zoological collection ever amassed in private hands, had a specific and incurable addiction to cassowaries. He bred them. He stuffed them. He gathered living representatives of every known species and sub-species at his parents’ manor house in Hertfordshire. Bewitched by their beautiful and highly variable neck wattles, he identified new species where there were none. He wrote a book, A Monograph of the Genus Casuarius, about them and made excuses for them, and he could never get enough. When his fortune ebbed and he had to face the prospect of giving up his bird collection, he wrote to all his collectors that no matter what restrictions his father put on his spending, they should keep stockpiling cassowaries. Across Europe, India and Australia, these stocks of birds became a kind of living escrow account, pecking and kicking, waiting for a change in Walter’s credit. When financial disaster struck, Walter had to sell off the collection of 300,000 birds he had spent a lifetime assembling, but he kept sixty-five cassowaries. By the time he died, in 1937, at the age of sixty-nine, he’d had each of the magnificent birds expertly taxidermied and displayed and in his private museum on the grounds of his family estate. But why did Rothschild prefer them above all other species?

Photo: A Monograph of the Genus Casuarius. London: 1900.

The cassowary (Casuarius casuarius) is a large, flightless bird that lives in the tropical rainforests of Northern Australia and in the jungles of New Guinea. It is the third-tallest and second-heaviest bird in the world, and its closest living relative is the emu. Other large, flightless birds in its class, like Australia’s “thunder bird” and the “elephant bird” of Madagascar, went extinct shortly after the arrival of humans in their habitats. The cassowary, however, has survived for at least fifty thousand years, since Australia and New Guinea were joined into a single continent called Sahul, through a mixture of stealth and aggression. Though the total population of cassowaries is estimated to be around ten to twenty thousand in Australia and New Guinea, the animals are rarely seen; they manage to avoid hunters and naturalists alike. After thirteen years working in the remotest parts of New Guinea, the mammologist Tim Flannery despaired in 2002 of ever seeing one in the wild: “I have found a footprint so fresh that water was still oozing into it, droppings still steaming and everywhere older signs of cassowaries. Yet so wary are these great birds that to this very day they have remained as invisible to me as ghosts.” In spite of their retiring nature, cassowaries can be dangerous if provoked. They are very fast, capable of running at thirty miles per hour through dense undergrowth on their strong, thick legs. Should you ever meet a cassowary, be sure to look at his feet, paying special attention to the inner toe, a five-inch long claw. This blade is why their kicks can be lethal. In 1926, a cassowary killed a young boy in Australia, severing his jugular vein.

Photo: A Monograph of the Genus Casuarius. London: 1900.

The elusiveness and violence of these birds has made them the object of many legends in native New Guinea populations. The Kwoma believe that the human race emerged from the feathers of the first cassowary. To the Kalam, Fore, Wiru and Baktaman, the cassowary is not a bird or a lizard or a mammal, but its own category of animal (birds are yakt; cassowaries are kobity). The Mianmin believe that all cassowaries are female, and that at night, they take off their feather skirts and turn back into women. The Kundagai are struck by the cassowary’s timidity and stupidity on one hand, and with its courage, stamina, and savagery on the other. When the Australians put an end to war in New Guinea’s Southern Highlands in the 1950s, the Mendi responded by turning to the competitive capture and exchange of cassowaries. When wars were still being fought among the villages along the Sepik River, the best way to finish off an enemy on the battlefield was always with a dagger made from a cassowary’s sharpened thigh bone.

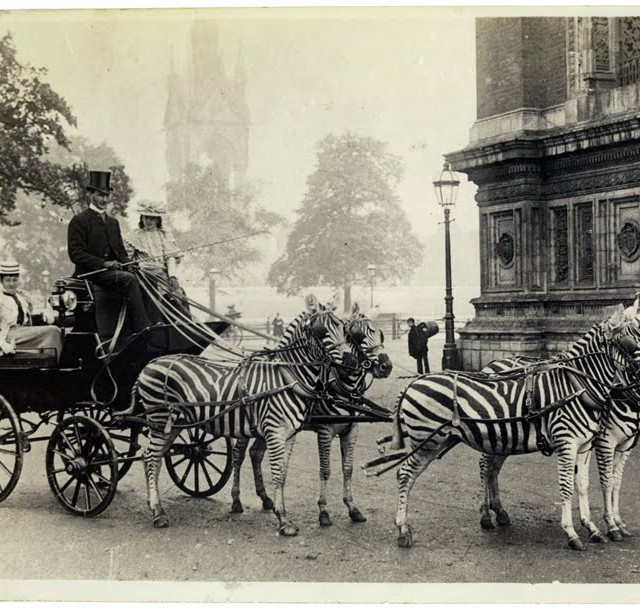

Walter was certainly aware of the cassowary’s violent tendencies. One day in the late 1880s, as his father Nathan (“Natty,” 1st Baron Rothschild) was making his way on horseback across the family’s grounds at Tring Park, one of Walter’s cassowaries chased him, and, missing its target, aimed several “dangerous, slicing, sideways kicks at his horse.” Walter forgave the bird its murderous attempt, but he was required from that moment on to keep all his cassowaries confined in a paddock. But by then, animal mishaps were nothing new at Tring. Walter’s giant lizards escaped from their greenhouse and ate all the arum lily shoots. His tame wolf picked fights with village dogs at the pub. In 1894, he drove a trap pulled by zebras up to the gate of Buckingham Palace, and watched on in terror as Princess Alexandra tried to pet one.

Photo: Flickr

From birth, Walter had been a golden child. He was his the eldest son, and would inherit the great fortune built by the English branch of the Rothschild dynasty. To his nurses, he must have looked like the infant Jesus. In a portrait of him at age ten by John Everett Millais, he looks like Little Lord Fauntleroy, resplendent in a black sailor suit with red trim, tall socks, leather buckle shoes, and an enormous red sash tied at the waist. He was painfully shy, and suffered from a debilitating stutter. And though he was frail as a child, Walter grew into a strange and enormous man, standing six-foot-three and just over three hundred pounds, with a habit of drowsing in his hammock in the nude. Rather like the cassowary, he was prone to long periods of silence punctuated by sudden eruptions of temper. And like many men with histories of complicated romantic escapades, he lived in mortal fear of upsetting his mother.

Walter’s interest in animals manifested early. By the time he was five, he could spot the difference between rare species of butterflies. At twenty years old, Walter’s love of animals had become a full-blown obsession. His menagerie at Tring included zebras, wild horses, wild asses, emus, rheas, several kinds of kangaroo, cranes, a marabou stork, a dingo and her pups, pangolins, a capybara, and a spiny anteater. He successfully bred zebras with ponies. He collected albinos of various species. When it was time to leave home for college, he arrived at Cambridge trailed by a flock of kiwis; he couldn’t bear to leave them behind at Tring. At twenty-one, Walter was put to work in the family business, but he showed no aptitude for finance. He hated his work. It’s unclear whether he had any real responsibilities. Still, he sat at a desk for nineteen years. By way of compensation, his father let him have a museum. The Tring Museum (although he always referred to it as ‘my museum’) quickly became one of the greatest natural history collections in the world, and a leading center of zoological research. Walter had collectors spread across the globe, scouring the earth for rare or unknown specimens; he employed four hundred such agents at one time.

Photo: A Monograph of the Genus Casuarius. London: 1900.

Collecting for Walter was demanding and, often, dangerous work. One collector died from dysentery, one from typhoid, and another from an unknown fever. He lost three men in the Galapagos. On one expedition, the ornithologist E. C. Stuart Baker had his arm bitten off by a panther. Walter paid little notice and gave meticulous instructions about which species he wished to acquire and in what manner they should be preserved. When one of his favorite collectors, C. M. Harris, arrived in San Francisco after a harrowing voyage to the Galapagos Islands, he was eager to head east and return to London. Walter ordered him to stay put and take care of the many live tortoises in his custody until they were well enough to make the journey to England. So, Harris rented a heated greenhouse and experimented with different diets for the turtles “until he found that they were not averse to bananas and liked squash.”

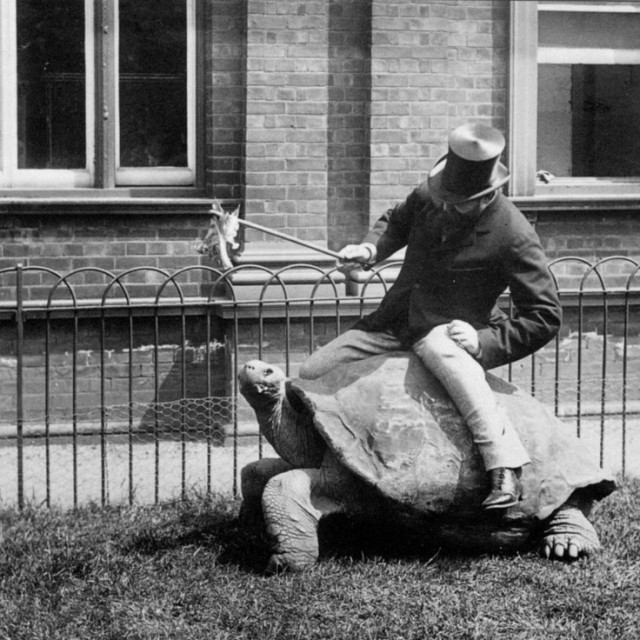

Giant tortoises were another of the great passions in Walter’s life. From 1900 to 1908, he rented an atoll in the Seychelles called Aldabra, in hopes of keeping this marvelous tortoise habitat safe. He wrote that he wanted to “save them for science”; he loved the prehistoric-looking giants, and tried to bring as many of them back to Tring alive as he could. Sometimes, he would get on their backs and ride them. He did his best to figure out the mysteries of their evolution and taxonomy. The prize of his collection was a great Galapagos Tortoise named Rotumah. When Walter acquired him, Rotumah was reputed to be the largest tortoise in the world, and was thought to be 150 years old. He had lived for many years on the grounds of a lunatic asylum in the suburbs of Sydney, where he had arrived as a chief’s gift from the King of Tonga to a well-known trader named Alexander MacDonald. “A most erotic and savage individual,” Rotumah arrived deeply chilled by his voyage to England by steamer and near death. He made a swift recovery, only to die two years later of “sexual over-excitation.” The tortoise was an erotomaniac, but his mate had been left behind in Sydney.

Walter had his own problems with sex. For years he kept two mistresses. One was named Marie Fredensen; the other, Lizzie Ritchie. He met them both at a party for King Edward VII. Marie was a would-be stage girl; Walter’s biographer wrote she was “As pretty as an Edwardian birthday greeting card, sweet, pert, cuddly, kittenish, simple, dependent, wheedling, adoring and light as a feather.” Lizzie was intelligent, worldly, temperamental, vindictive, a “bit crazy” and a great listener. Walter installed each of them in separate London apartments. Neither woman knew about his relationship with the other, nor did anyone in his circle; he never once spent a night under either of their roofs. Eventually though, Lizzie found out about Marie and flew into a rage. She bought a house next to his museum in Tring and tried, repeatedly, to confront his mother. Marie was equally distraught. The stress of his various entanglements became too much, and Walter decided he could no longer stand to read his mail. Instead, he placed his unread correspondence in two large wicker baskets, one reserved for the blackmailer and the other for the mistresses and other matters. When each basket was full, he locked it. For two years, the baskets piled up until they filled a whole room. When his younger brother Charles found out about the ruse in 1908, it took him and four clerks working day and night six weeks to sort out the mess. On Walter’s behalf, Charles worked out a settlement with both women. Walter agreed to buy each of them a house and gave them a 10,000 pound per year allowance. Each woman separately forced him to agree to never see the other one again. Finally free from his burden, Walter went on a collecting expedition to the Sahara, which he kicked off with a tremendous party in Algiers. In the desert, he survived a terrible sandstorm and captured a beautifully colored spine-tailed lizard and a fine specimen of a rare butterfly named Euchloë pechi.

Like Walter, Charles was a naturalist, though less single-minded in his pursuit. His main interests were irises and fleas. He gathered more than ten thousand specimens of fleas, and his greatest triumph was identifying which species of flea carried the plague. His own daughter, Miriam, followed in his footsteps, and spent most of her life working out the taxonomy of the fleas in her father’s collection. Taxonomizing fleas was tricky business; it required patient work with a microscope and careful attention to tiny genitalia. Miriam’s catalogue of her father’s collection runs to seven volumes. It is a work of interminable dullness, until she gets to the matter of “the amazing array of secondary devices and structures in the male.” Miriam said that she first believed in God when she “discovered that the flea had a penis.”

Even though Miriam was an enthusiastic entomologist, Walter rarely acknowledged her. He was awkward around his younger relatives. One of the few things she remembered him saying about her was a remark to his mother: “Mama, isn’t it strange that Miriam is completely square?” Still, she eventually became his biographer, and he left her “one of the most original and delightful bequests of all time,” which included 140 mother-of-pearl handled fish knives (the forks were all missing), 600 copies of old sporting prints, two live long-beaked echidnas, 500 parakeets, a Pyrenean Mountain dog, and several tortoises in the custody of the London Zoo. Reflecting on what studying the natural world had taught her, Miriam wrote: “As a species, we are less successful than rats and not as well adapted as the cockroach. We can, however, change our mind.”

Marie and Lizzie put a strain on Walter’s finances, but the true reason he eventually had to give up his collection only became apparent after his death. Walter destroyed the baskets full of his unread correspondence, but for some reason, he left one of them behind. It revealed that, through all the years he was with Lizzie and Marie, another of his former mistresses was blackmailing him. The ruse went on for some forty years and must have involved enormous sums, both in direct payouts and losses from disastrous speculation on the stock market, made at the blackmailer’s request. Only Walter’s sister-in-law and her daughter Miriam ever learned the truth. In her biography of her uncle, Miriam refuses to say who reveal the blackmailer’s identity, except to say that she was “charming, witty, aristocratic and ruthless.” She was also married. At some point, Walter met her sons, who had befriended his nieces. Otherwise, he never mentioned the matter, not even to his brother Charles.

Walter’s last years were marked by tragedy. Charles shot himself in a Swiss hotel at the age of forty-six. The mysterious blackmailing went on for forty years, eventually forcing Walter to sell off his collection of birds to the American Museum of Natural History in New York in 1931. When Lizzie heard of the sale, she asked for a slice of the money, but added that she would be saving up, “To help you buy back the birds.” He grew ill, and stopped spending as much time in the museum; within a few years, he was dead. For his tombstone, he chose a passage from the book of Job: “Ask of the beasts and they will tell thee and the birds of the air shall declare unto thee.” Along with his curators, Walter described five thousand new species (even if a few didn’t stick in the end). He proposed no grand system; he simply wanted to possess the world in all its endless variety. Blessed with boundless resources, he was able to amass a good deal of it. But he was trapped by his personality, and many of his designs came to ruin. Better to remember him as he was in his prime: astride a tortoise, followed by birds.