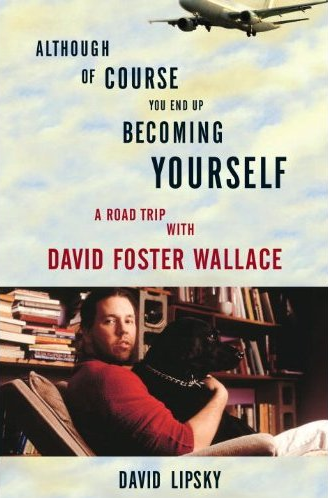

Booked Up: 'Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: a Road Trip with David Foster Wallace...

Booked Up: ‘Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: a Road Trip with David Foster Wallace,’ by David Lipsky

In 1996, Rolling Stone sent David Lipsky to accompany David Foster Wallace on the last leg of the book tour for Infinite Jest. The piece never came out. Instead, many years later, David Lipsky wrote a book about those five days. During the time they spent together, Lipsky couldn’t have known that Wallace was largely concealing a heart-attack-serious history of depression, drug abuse, hospitalization and ECT; they couldn’t discuss Wallace’s real involvement with 12-step programs (see Tradition, Eleventh) or the medication he was taking the whole time they were together; couldn’t address the real fragility of his recovery. Wallace took his own life twelve years after the events described. These lacunae, filled in by the modern reader, provide a dizzying, scary undertow to the book, tingeing the whole with dread, the if-they’d-only-known feeling of stories like “Jean de Florette.”

A sound drubbing should be administered to anyone who attempts to compare the film My Dinner with Andre to this book, as many careless readers doubtless will. It’s not about one wild, brilliant, look-at-me performer and one bemused, scholarly audience-member. It’s a road picture, a love story, a contest: two talented, brilliant young men with literary ambitions, and their struggle to understand one another.

I can’t tell you how much fun this book is; amazingly fun, even for a Wallace fan who is still devastated by his death. You wish yourself into the back seat as you read, come up with your own contributions and quarrels. The form of the narrative, much of which is a straight transcription of the interview tapes, together with the wry commentary of the now-mature and very gifted Lipsky, is original, and intoxicatingly intimate.

They were so much alike, these two, right at the threshold of what they’d spent long years hoping would be distinguished careers. Long-haired, smoking, keen on girls, books, TV and movies. Writers both. One of them had just hit the cultural jackpot. You can imagine the tensions here, and Lipsky doesn’t shrink from addressing them. There is professional jealousy vs. professional caginess, wariness. The desire to be liked; the desire to be a “success” as a writer, when one had so clearly “made it” and the other, not quite yet; there was a lot for them to overcome in order to reach one another.

DL: How’d it feel, though: “As if the book is a National Book Award winner already”?

DW: I applauded his taste and discernment. How’s that for a response? What do you want me to say? How would you feel? I can’t describe it; it’s indescribable. You speculate and I’ll describe.

[Slightly mean/clever smile]

DL: I’d feel I’d known all along it was OK, and here was someone actually saying what I’d hoped to hear said.

The younger Lipsky felt a little bit outgunned sometimes by the success and the teeming intellect of Wallace, though he gives as good as he gets; most of all, Lipsky has in spades the one thing that Wallace always valued most, that elusive thing he used to call “authenticity.” Both the young Lipsky and the older, wiser one who put the book together have it. He is never afraid to say just what’s on his mind, even when he knows it’s going to cost. I’m going out on a limb here, but I suspect that what was also going on was that Lipsky (stable, elegant, and confident as he appeared) never knew, maybe still doesn’t know, that Wallace must have been as jealous of him as he was of Wallace. As irritated at him for being smart, as annoyed at him for being handsome.

So it’s very satisfying, that way, in terms of offering many, many interesting avenues of conjecture.

And when they finally are at ease together, after a whole lot of edginess and caginess of the type that will be very familiar to intelligent, ambitious young people everywhere, when they forget about the risk and come out from behind their respective barricades, it’s exhilarating. There’s a glorious discussion of television, including the respective parental curbs put on the boys’ TV time, growing up. Wallace was only allowed two hours per day on weekdays; Lipsky says, “I preferred my dad’s house over Mom, one reason, because no restrictions on TV at all.” Boy it is good, that part. The book just takes flight in this developing pleasure of mutual understanding and trust. It brings Wallace down to a human scale, in a penetrating and evocative way. Not like bringing down a Goliath, though; what you have is just the two Davids.

If anyone says that David Lipsky’s personality obtrudes too much into this book, I can only say that such a person must not have known Wallace or his work too well. Well, no. I can also say that I am willing to come over and punch such a person in the nose. Wallace was the opposite of a monologist. I saw this at his readings, over and over, an inexorable demand for dialogue. (This, incidentally, is the main reason why Infinite Jest is so “difficult”; the author needs you to work, to come his way.*) Invariably, instantly, Wallace would start asking any interlocutor the questions. Some might have seen this as a way to regain control of the wheel, but I thought it more like a way of getting his balance, because he obviously loved conversation but he was very shy, too, didn’t care for curvetting before the public. Didn’t see himself in any way as a dispenser of wisdom. So he draws Lipsky out, bit by bit, and, well. I had a massive crush on both of them by the end, and I’m sure I won’t be alone in that.

(This book will make the most phenomenal movie, by the way, Hollywood!)

There is quite a lot more here to unpack but please, we can do that after you’ve read the book. So just go, take a sleeping bag, camp out at the bookstore. I’ll be here when you get back.

*Because it articulates Wallace’s position vis-Ã -vis his work so well, Lipsky has provided with this book a really splendid introduction for any reader who is thinking of tackling Infinite Jest. It will make IJ incalculably easier to understand, more so than any other commentary or analysis I’ve yet seen.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo: The Macho of the Dork and