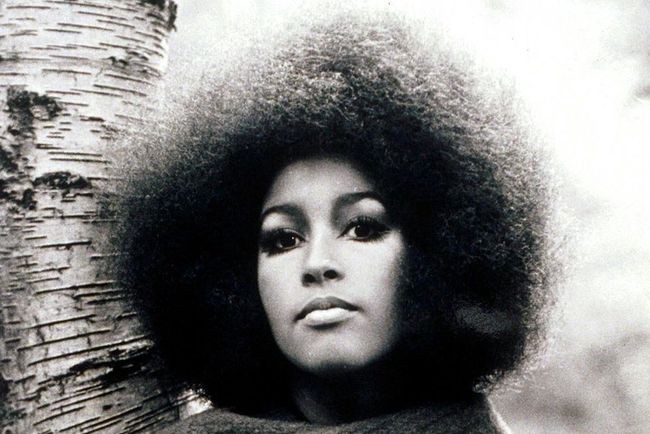

Best Forgotten: 'Real Life' by Marsha Hunt (1986)

Mick Jagger’s first and best baby mama

You’ve read about Mick Jagger’s most recent feat of paternity — in December he signed for baby number eight, with mother number five — so you’ve seen the name Marsha Hunt: a news story can’t inventory Jagger’s children without it. Hunt is the mother of Jagger’s first child, Karis, who was born in November of 1970, having gestated for a period roughly as long as her parents harbored affection for each other.

In articles I’ve read over the years, Hunt has always presented as self-possessed and disinterested in dwelling on her stratospherically famous onetime paramour. Still, because her name is forever reproductively linked with his, it’s been hard not to draw the conclusion that having Mick Jagger’s baby amounted to a career move. Recently, I tested this idea by tracking down and reading Hunt’s two out-of-print memoirs — 1986’s Real Life and 2005’s Undefeated — and I’ve reached a new conclusion: for Hunt, having Mick Jagger’s baby was probably a career dampener.

In 1966, the Philadelphia-born Hunt’s restless spirit lured her from her studies at Berkeley to London, then fully swinging; she never again called the United States home. “American politics and its class system, better known as racism, had shaped and limited my life and future in ways that I couldn’t know or fully comprehend until I was outside it,” she writes in Undefeated. “When I arrived in London…my nationality became my identity, and the Negro label took a back seat.”

Not that being an American black woman in London at that time didn’t have a certain cachet: “Motown was the sound of the day, and anybody looking and talking vaguely like a Supreme was considered gorgeous,” Hunt writes. In 1968 she landed a modest role in the London production of the Broadway smash Hair; six months later, she signed a record contract.

In Hair, Hunt sang a Supremes parody called “White Boys” backed by two West Indian women, and the white boys did come calling. Hunt briefly romanced Marc Bolan, when Tyrannosaurus Rex was just becoming T. Rex, and, nudged by her producer, recorded a couple of his songs. After scoring a minor hit with her debut single, Dr. John’s “Walk on Gilded Splinters,” she was contacted on Jagger’s behalf to find out if she would pose in a slutty getup for a publicity photo for the Rolling Stones’ forthcoming single, “Honky Tonk Women.”

Jagger had picked the wrong beautiful black woman. Hunt writes in Real Life, “The last thing we needed was for me to denigrate us by dressing up like a whore among a band of white renegades, which was an underlying element of the Stones’ image.” Hunt’s no to Jagger’s people inspired a phone call from Jagger, who paid her a visit that evening. She writes of their ensuing relationship in levelheaded terms — “We were not so much lovers as friends. There were no silly cat-and-mouse games” — and indicates that she wanted nothing in particular from him: “I needed my own independence and didn’t expect him to relinquish his.” She wasn’t even a Stones fan.

Meanwhile, Jagger was sufficiently besotted with Hunt to write “Brown Sugar” about her. She suspected he appreciated that she wasn’t into drugs, unlike his for-the-most-part girlfriend, the angelically opiated Marianne Faithfull. Hunt didn’t get too caught up in Jagger’s world: “I always feared that my association with him would crowd out my own identity. I never wanted to be known as Mick Jagger’s girlfriend.”

Well, she tried. But make no mistake: it was Jagger who proposed that they have a baby together. Hunt’s inkling concerning his motivation sounds just right, especially given subsequent media accounts of the long-standing Jagger-Richards rivalry: “Marianne had miscarried the baby that they would have had around the time that Keith Richard’s [sic] son Marlon was born. It was understandable that he considered having a second try.”

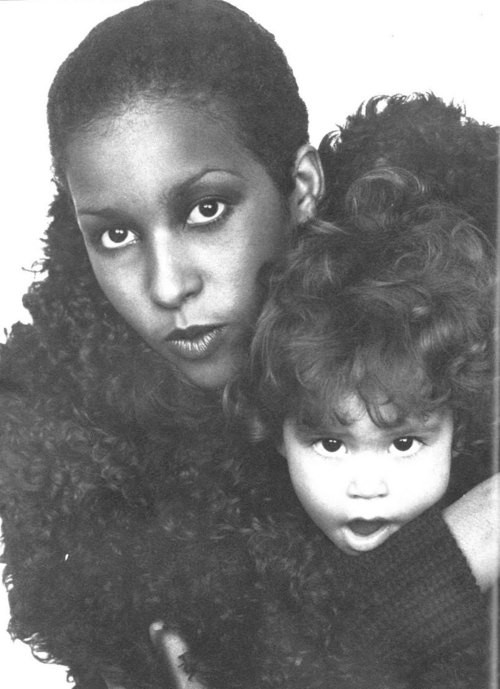

For Hunt, having a baby meshed with the day’s starry-eyed delusion that achieving happiness was a simple matter of letting the sunshine in: “I didn’t really expect it to change my life in any way. I was making money and had a lovely home. My prospects were excellent, and I was sure they’d continue to be so.” She and Jagger wouldn’t live together. As for his role in their child’s life: “We were supposed to be the sophisticated embodiment of an alternative social ideal — parenthood shared between loving friends living separate lives.” That’s hippiespeak for, “Mick and I made no financial arrangements regarding the support of our shared offspring.”

After Karis was born, Hunt scooped up pretty much any job that bounced her way, and not just music gigs: she modeled, acted in the dodgy English horror movie Dracula A.D. 1972, and did a soft drink commercial in Germany. The last was embarrassing, yes, but better than selling her story to the tabloids, and better than asking Jagger for a loan, as she had to do more than once.

Hunt made money on the road, and in 1972, while she and her backing band were on a German tour on which she had brought along Karis and a nanny, the toddler spilled hot tea all over herself. Hunt insisted on an immediate return to England, where she felt that Karis would get better medical care. This meant canceled gigs, which meant less income and less exposure to potential new fans. Hunt asked Jagger to spring for half of Karis’s hospital bill; the money never arrived. Despite the “sordid connotations” of a paternity suit, Hunt went for it: “After two years, I had to stop pretending that he would assume his duty.”

When the story went public, Hunt found herself something of a social pariah: “I went from being tagged ‘the girl from Hair’ to ‘the girl who sued Mick Jagger.’” She writes that she sensed a chill in the air when she interacted with shop people and the parents of Karis’s classmates. Hunt hadn’t tried to hitch a ride on a rock star, but if she had, her reputation would have scarcely emerged more sullied.

The paternity suit wasn’t resolved until 1979, when Jagger was told to provide Hunt with an annual settlement for Karis as well as a trust so that the girl wouldn’t be destitute if her mother suddenly dropped dead. Hunt personally received no money — fine by her — but everyone thought she had made off with a mint.

At the time the suit was resolved, Hunt was staying in Los Angeles, trying to find a distributor for a record she had made in Germany; to keep financially afloat she did housekeeping for friends while Karis was at school. When nothing happened in L.A., Hunt quit the music business, having promised herself that this would be her last go, since, as she wrote in perhaps the least diva-ish sentence in the entire world, “Music was only acceptable as a career if it could provide us with an income.”

Hunt redirected her creative energies to acting and writing. She has since published well-received novels centered on the African-American experience and an absorbing book about rescuing her long-presumed-dead grandmother from a U.S. nursing home. But the standout is Real Life. It’s flawed — it loses its bearings toward the end — but it’s an uncommonly clear-sighted account of the music scene of the 1960s and 1970s as witnessed by an inside-outsider disinclined to do anything that was expected of her. The book also reinforces an idea that I’ve long found to be true: a story about almost making it is usually more interesting than a success story.

At the end of Real Life, Hunt refers to her “charmed life,” but a reader may reasonably wonder, How so? Among Hunt’s disappointments: she blew a couple of film auditions, including one for Sidney Poitier, maybe because she was holding the script in one hand and Karis in her other arm; record contracts came and went or were not quite signed (“Managers and record-company people that I spoke to weren’t at all prepared in 1980 to accept that a [black] woman could find a market doing rock, which was considered white music”); and Richard Branson yanked funding for a musical she wrote because the London press said mean things about the dress rehearsal.

The “charmed” part of Hunt’s life, then, is presumably having had Karis, who surely, like every kid, couldn’t help but divert her parent’s attention from her work, deprive her of sleep now and then, interrupt her creative bursts, and so on. What stymied Hunt’s musical ambitions may have been not just a tarnished reputation and the business’s assumptions about black female singers but the fact that Karis was never not the first thing on Hunt’s — and only Hunt’s — mind.

A pulsebeat in Undefeated, which chronicles Hunt’s experience with breast cancer, is her anxiety about completing a book she’s been writing about Jimi Hendrix, who had been, like her, a black American in Britain in the late 1960s. She tells the reader that she doesn’t have a publisher, and at this writing I can find no evidence online that she has found one. If her Hendrix book comes out, may it get more column inches than news of the next Jagger baby.

Nell Beram is coauthor of Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies and a former Atlantic Monthly staff editor. She writes occasional Best Forgotten columns for The Awl.