The Sun Goes Down in the West

by Amy Brady

In 1977, Lorraine Brown, a professor at George Mason University, sat down with retired director, teacher, playwright, and actress, Mary Virginia Farmer, to ask whether a play she directed and helped write nearly forty years earlier, The Sun Rises in the West, contained communist propaganda. Rather than answer the question, Farmer asked Brown to shut off the recorder.

For Farmer, such questions were frustratingly, perhaps even terrifyingly, familiar. In 1951, a full fifteen years after The Sun Rises in the West became a huge hit for the Los Angeles Federal Theatre Project, Farmer was called before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee to testify whether she had ever participated in anything “subversive,” the committee’s code word for Communism. The committee questioned eighteen witnesses the day they called on Farmer. Four of them, including Farmer, went into the record as “unfriendly” for refusing to answer their questions. She never worked in Hollywood again.

Farmer’s story isn’t told in Trumbo, the recent film starring Bryan Cranston that chronicled the resistance of the Hollywood Ten, a group of men working in the film industry as screenwriters and directors who were blacklisted and jailed for their refusal to cooperate with HUAC. It isn’t told anywhere; Farmer’s work as an artist and political agitator has been relegated to literal footnotes in academic treatments of the history of American political theatre and Hollywood’s blacklist, if mentioned at all. But her work is worth remembering. Her achievements — including an acting and teaching position in New York City’s famous Group Theatre, the company that nurtured the talents of Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Clifford Odets — were shot through with political activism during a time when the labor movement, for all its gender-equality rhetoric, still reinforced traditional gender roles among its constituents. That activism ultimately ended her career.

When the national economy collapsed in 1929, ushering in the worst economic depression in American history, artists in nearly every medium — song, literature, radio drama, theatre — responded with work that spoke to the crisis in some way. Among them, theatre artists tended to present the most hopeful visions for the future. Their plays offered calls to action to make the world a more equitable place, whether through vaguely described “collective action,” or via “Communism,” which, for nineteen-thirties American artists, looked less like what was manifesting in Russia at that time and more like what we would call progressive liberalism today.

By the early thirties, there were enough amateur and professional theatre groups making political plays to constitute a movement that most historians refer to as the American workers’ theatre. Historians also agree that many of these plays were not very good. Lee Papa, for example, has described them as “fascinating, moving, [and] occasionally frustrating,” but compared to how they were received at the time, his description is generous. It’s not that the workers’ theatre didn’t care about aesthetics — in fact, they were among the first artists in America to study Stanislavsky’s method and other modernist techniques that would eventually become hallmarks of American acting and theatre and film design — it’s that it emphasized politics over aesthetics. (In one misstep, the New Playwright’s Theatre attempted to achieve verisimilitude by performing Upton Sinclair’s two-and-a-half-hour play Singing Jailbirds in complete darkness.)

The Group Theatre is often remembered as a “workers’ theatre,” but it differed from others in the movement in a number of important ways: Its performances were professionally staged, its actors were experienced, and its aesthetic experimentation, for the most part, worked for audiences. Farmer was one of the Group’s first company members, one of the “Chosen Ones,” as historian Helen Chinoy calls them. Much about the Group appealed to Farmer’s political and artistic sensibilities: The company operated as a collective, living and writing plays together; they weren’t afraid to experiment; and they were some of the most ambitious people she had ever met. But Farmer grew impatient with the Group’s “middle-class politics.” Moreover, she disliked most the men of the Group, particularly Lee Strasberg, who she felt treated women like children. In a letter, she told him as much:

[T]hough we may and indeed must come as children to learn something, we must come also as adults to sift, digest, to make these new things our own, through the processes of our own beings.

In early 1935, seeking to strike out on her own, Farmer moved downtown to help form what would become one of the most radical theatres in New York City, The Theatre Collective. Like the members of the Group, the Collective lived and worked together, but instead of devising plays that spoke to a middle-class audience, the Collective staged plays that doubled as leftist treatises about the dangers of capitalism.

Farmer taught young actors in the Stanislavsky method and other techniques she learned from the Group, such as improvisation and character writing. Unlike the Group, the Theatre Collective mounted plays that were in-line with CPUSA talking points and general ideology. Notable, too, was the Theatre Collective’s use of full-length, realistic plots, which most workers’ theatres did not have the talent nor resources to perform. How good were these shows? Unfortunately, little documentation of the Theatre Collective’s performances survived the thirties, and I wasn’t able to find any extant reviews. Given the general quality of the workers’ theatre and Farmer’s above-average acting and directing skills (which Flanagan would later herald as “revolutionary” in at least two senses of the word in her memoir Arena), the Theatre Collective’s shows were probably good, but not great.

Farmer’s reputation as a director and teacher grew, and later that same year, Howard Miller, Deputy Director of the Federal Theatre Project, called to offer her a job. At first she refused — the Collective was going too well — but Miller persisted. In September 1936, she accepted the position as director of a new, federally funded experimental theatre troupe and moved to Los Angeles. The Federal Theatre Project, the artistic arm of the Works Progress Administration, lasted only four years, from 1935 to 1939. But in its short life, it generated more controversy than all the earlier workers’ theatres combined.

If most people today know anything about the Federal Theatre Project, it’s what they learned from Tim Robbins’s movie The Cradle Will Rock. The movie depicts perhaps the most remembered moment in the project’s short history: Working for the New York City Federal Theatre Project, playwright and musician Marc Blitzstein wrote The Cradle Will Rock, a musical about labor unionizing and other working-class concerns. Directed by Orson Welles, the musical garnered a lot of publicity as well as the attention of congressional figures who found the show’s leftist themes unfit for a federally-sponsored stage. An act of Congress canceled the show, and on opening night, the theatre’s doors were locked with a bolt and chain. Outraged at the censorship, Welles led his cast and audience members (who received zero notice that their tickets would not be honored that night) to a second theatre nearby, and Blitzstein, fueled by conviction and adrenaline, took to a piano on stage. The actors’ union forbade any of the cast to perform on stage that night, so they joined the audience, singing their lines from the rafters. The movie is based on real-life events, but most were Hollywoodized (Blitzstein never counted among his constant companions a hallucinated Bertolt Brecht). The film also suggests that the bare-boned performance of The Cradle Will Rock directly caused the Federal Theatre Project to close by fueling congress’s suspicions that its actors, particularly those living and performing in New York City, were politically subversive. In truth, Congress’s fear of “un-American activities” stemmed as much — if not more — from the work of Farmer and her experimental arm of the Los Angeles Federal Theatre Project, called the Southwest Theatre. It would be this work that would later land her in front of HUAC.

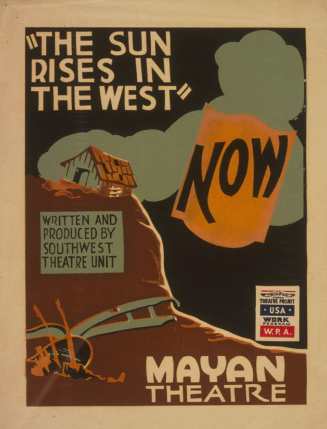

The Southwest Theatre operated only three out of the Federal Theatre Project’s four years of life, but it managed to produce five plays, including The Sun Rises in the West, the company’s only original work. The play, which focuses on the deplorable living conditions suffered by Dust Bowl migrants in California, was based on real-life people. In the summer of 1937, Farmer took her two best playwrights, Donald Murray and Theodore Pezman, to meet John Steinbeck, who was conducting research on what would become The Grapes of Wrath. Aided by brandy, the four writers spent the night hammering out the play’s basic structure and character arcs. Steinbeck’s name never appeared on the writing credits of the play, but in a 1976 interview, Pezman heralded his contributions, calling him one of the “finest playwrights” he ever knew.

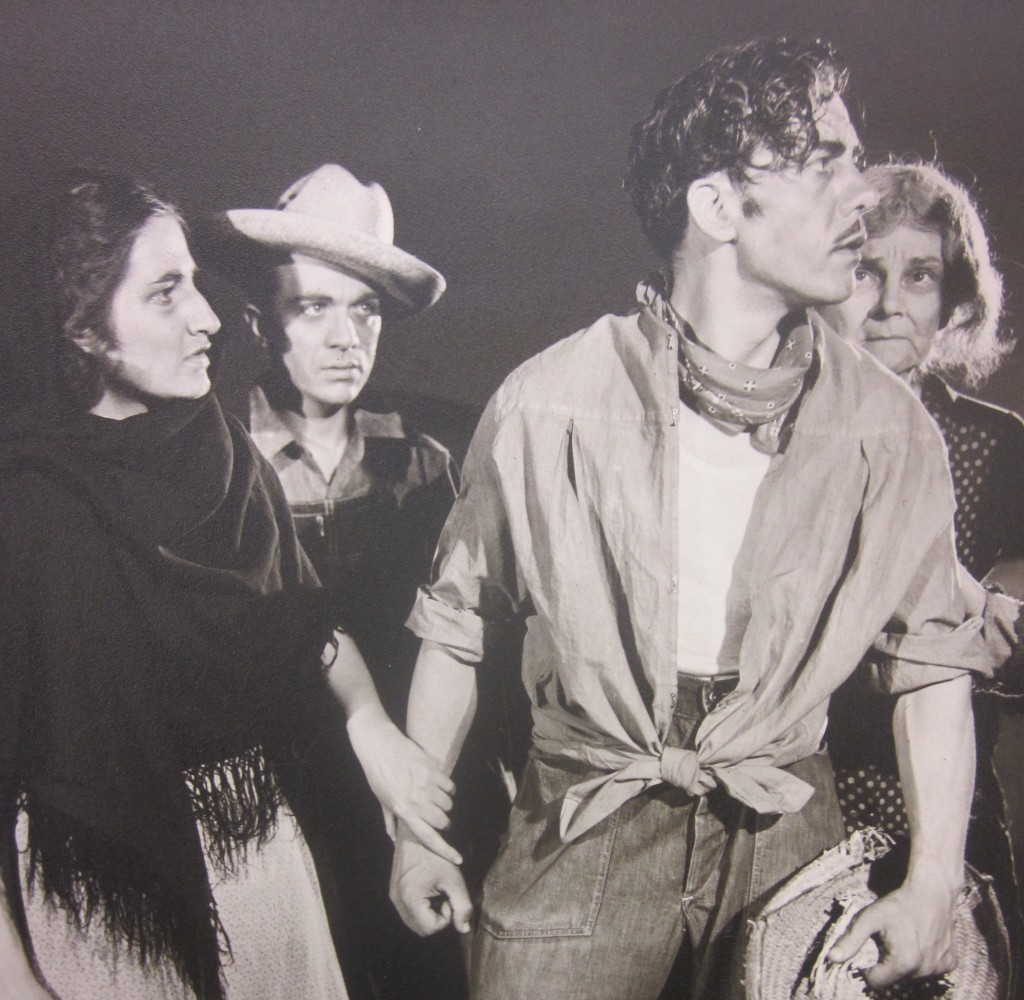

Not long after this meeting, Farmer and her playwrights traveled deep into California’s agricultural valleys to conduct field research on the Dust Bowl migrants’ way of life. They spoke to the migrants about why they moved west and whether they would ever go back. After all, life in California was not what most of these migrants had expected — they worked as farmhands instead of farm owners, and pay and living conditions were nearly as poor as what they had left back home. Most answered taht they would not return, mostly because they didn’t have the money to do so. The three writers kept a notebook filled with observations about what the migrants wore and ate and how long they worked each day. They took note, too, of another group of migrants that shared the Dust Bowl farmers’ work load but who often received even less pay — Mexican-American migrants who had been travelling throughout California during the growing seasons long before the (mostly white) Dust Bowl farmers ever arrived in the state.

The inequality between the two groups of “pickers,” as the farm managers called them, was not lost on Farmer or her playwrights. In its final form, The Sun Rises in the West depicts several confrontations between the Dust Bowl and Mexican-American migrants and ends with a call for collective action to push back against racist wage inequalities and the general poor treatment both groups received from their employers.

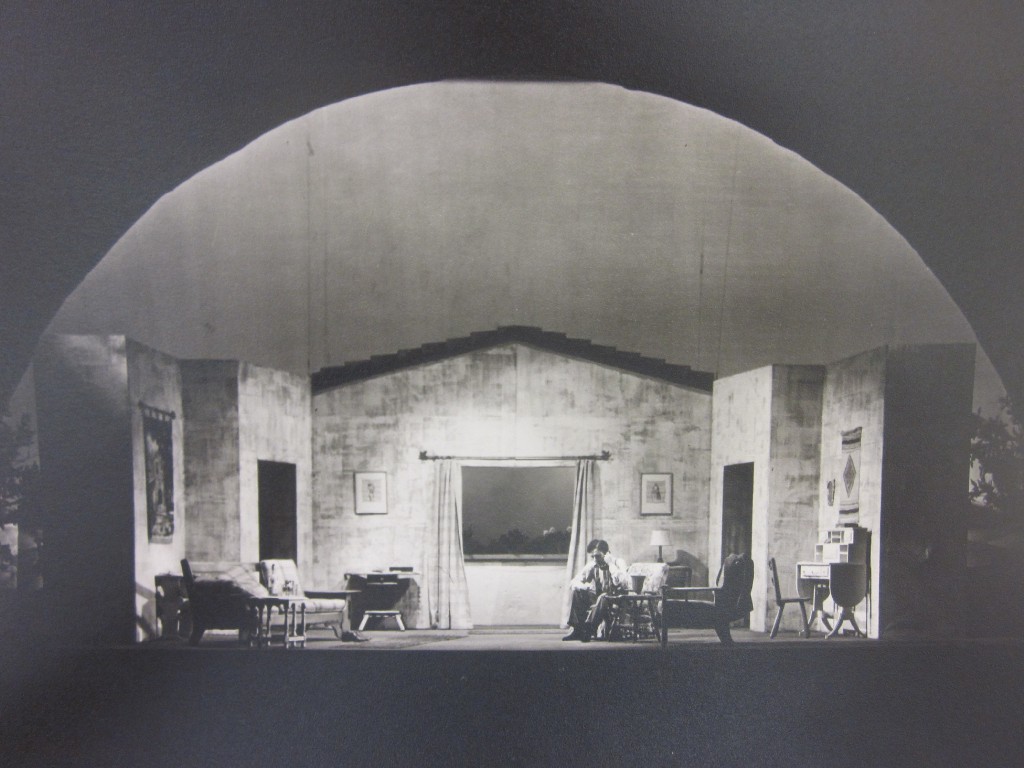

When the play opened at the Mayan Theatre in Los Angeles in July of 1938, audience members loved it for its authentic representation of Dust Bowl migrants. “Conditions were portrayed, not exaggerated,” noted one member of the audience on opening night. “Plays of this sort picture life as it is for these people.” For others, the authenticity was hard to take. “Well done, but not the type of play I like,” said another audience member, who then continued: “We get enough of this in real life.” The realism of the play’s themes were echoed in the realism of the set design. Early scenes took place in the Dust Bowl family’s Midwestern home, its interiors dingy from dust, a plant symbolically dying in the corner to represent drought. Furniture was sparse on stage because much of it, the script tells us, had been used as firewood.

Despite its emotionally trying subject matter, the play was enough of a success to run for an additional two weeks in San Francisco. For this run, Steinbeck wrote an informational pamphlet about Dust Bowl farmers that actors distributed to audiences as they filtered into the lobby. Each night before the play began, an actor would urge audiences to take “the migrant problem” seriously. The stage manager would then project on the stage curtain clips from Pare Lorenz’s The Plow That Broke the Plains, a documentary that was generating a heated controversy of its own for depicting the Great Plains as no longer suited for farming.

The Sun Rises in the West — with its politically charged ending, promoting what essentially amounted to interracial unionizing — got the attention of Alexander Leftwich, a Regional Director of the FTP. It was his job to ensure that the western Projects produced plays suitable for a government-funded stage. This play, he felt, was too “leftist,” so he looked further into the backgrounds of those who produced it. When he discovered Farmer’s history with the Collective, he tapped one of the Southwest Theatre’s writers, Rena Vale, to “keep tabs” on her colleagues and report any “subversive activities.”

Here, it is important to remember that while Farmer was allowed to pick many of the people who joined the Southwest Theatre, she worked in conjunction with other, more mainstream troupes within the larger Los Angeles FTP, which gave work to perhaps some of the most conservative theatre artists in the country: aging vaudevillians and scriptwriters who were skeptical of lefty New York. Vale was intensely conservative and highly suspicious of any activity that didn’t read to her as “American.” She took note of anything said or done during rehearsals that she deemed “subversive” and submitted her notes to Leftwich on a weekly basis. While The Sun Rises in the West certainly would be used as “evidence” of Communist belief circulating among the Southwest Theatre, it was the company’s living arrangements that provoked the most suspicion from Vale and ultimately Leftwich. Wanting to model her troupe after the successful Group and Collective theatres, Farmer invited the Southwest Theatre members to share a house with her in Los Angeles, where they spent evenings reading and writing plays, and of course, talking politics.

As early as 1937, Leftwich began handing over Vale’s reports of “subversion” to Dies, who was at the time form a nascent version of HUAC known as the Dies Committee. In 1938, Farmer’s playrights, Murray and Pezman, were asked to testify. The record of what either man said when testifying has been lost to history, but it’s fair to assume that their mere appearance before the committee had a negative impact on their careers. Murray, who had once sought to make it as a screenwriter, settled for work in the left-wing Chicago Repertory Group, and later, as a writer of short educational films. Pezman eventually found work in the State Probation Department but lost his job when his supervisor discovered that he’d failed to note the congressional investigation on his job application.

Vale continued to do her part to fuel the Red Scare, including appearing before HUAC in 1940 and writing for the Los Angeles Times one of the most scathing editorials ever written about the FTP. Titled “Stalin Over Los Angeles,” the piece detailed the history, as Vale interpreted it, of communism in California:

By 1938 the Kremlin’s formidable machine in California included the American League for Peace and Democracy and the Anti-Nazi League which were influential in moviedom, and the League of Women Shoppers, rear guard of the CIO, to say nothing of a number of forums and independent clubs which had been captured and indoctrinated by communists disguised as liberals.

The piece was later anthologized in an issue of The American Mercury, which included other strange think-pieces from 1940 such as Dorothy Miller’s pseudoscientific “What Are the Brain Waves Saying?” and Anthony Turano’s “Common-Law Wives,” an outraged examination of all the ways that women could blackmail their husbands through common-law marriage.

The Southwest Theatre dissolved when Congress officially ended the Federal Theatre Project in June, 1939. The Sun Rises in the West was the last play the group ever performed. In her 1940 memoir of the Federal Theatre Project, Flanagan lauded the play as “a potent source of drama not only for Federal Theatre but for the theatre and cinema in general.” As it came to be, this potency would have a rippling effect throughout the rest of Farmer’s life.

When Congress dismantled the Federal Theatre Project in 1939, Farmer, like most other actors and directors working on the Los Angeles Federal Theatre Project, found work in film and television. In 1940, she joined the Hollywood Theatre Alliance, a group of filmmakers who also wanted to “do good theatre that reflected…the social scene.” She secured mostly small and uncredited acting roles throughout the forties, but in 1950, she played Duenna in the film Cyrano de Bergerac, starring the Oscar-winning Jose Ferrer as the eponymous, love-sick lead with a large nose. That same year, she earned a small but recurring role on the TV series Fireside Theatre. Farmer was far from being a household name, but she was supporting herself doing what she loved. Then, on September 21, 1951, Senator McCarthy called her before HUAC.

Two years earlier, Farmer’s friend Clifford Odets had appeared before HUAC, and he had, to use the parlance of the day, “named names.” (Odets’s wife suffered from a number of ailments, and he couldn’t afford to lose money). As a “friendly witness,” Odets lost friends, but he stayed off the blacklist. He would go on to write and direct two more stage plays and two films before his early death in 1963 from colon cancer.

Farmer’s personal life remains largely a mystery, but whatever her reasons, she refused to cooperate with McCarthy. Perhaps this would come as no surprise to those who knew her well. Murray described her thusly: “She was respected and a controversial figure. Autocratic but also permissive in a way.” With Murray’s description in mind, it’s not hard to imagine Farmer, by then in her fifties, sitting stubbornly before McCarthy’s committee, reading her prepared statement with something akin to professorial conviction.

In her statement, which amounts to approximately four typed pages, Farmer at once affirms her “Americanness” while espousing the opinion that openness to multiple ideas and ideologies results in a stronger mind, not a weaker American. It was a rhetorical trick used by a generation of lefty American artists who were forced to defend or otherwise account for their politics, whether officially before a committee or unofficially in the court of public opinion. In a particularly salient passage, Farmer aligns her belief in maintaining an open mind with a pursuit for intellectual honesty, going even as far as to encourage controversy as a means to understanding “the nature of man”:

A man’s academic education, his bookshelf, and his list of subscriptions to publications, should be alike in their heterogeneousness. In the universities, every point of view should be available to the student, and its teacher and advocate honored in his activity. How can there possibly be a choice of the best otherwise? The bookshelf which is significant of intellectual activity and eagerness in the mind which furnished it should exhibit opposites, not a mere line of confirmation of one interpretation of thought or action. […] There can be no intelligent choice of opinions and action without contrast and comparison, advocacy and criticism. And the more open the controversy the better, without fear that disagreement from any source can bring any form of retribution. The mature man is the sum of the choices he has made from the vast array of subject and interpretation open to his investigation.

Farmer read her statement the same day that John Howard Lawson, a well-known screenwriter and acquaintance of Farmer’s from their radical theatre days in New York, appeared before HUAC for the second time, five years after his initial appearance — the one that landed him in jail as a member of the Hollywood Ten. The first of HUAC’s “unfriendly” witnesses, Lawson famously retorted, “I am not on trial here, Mr. Chairman. The committee is on trial here before the American people.” Lawson’s testimony, like that of the other Hollywood Ten, contributes to a body of HUAC testimonials that, together, represent some of the most fascinating rhetorical acts of resistance ever to be made public record. It makes sense, then, that the story of the Hollywood Ten — and the Hollywood blacklist more generally — continues to be re-told through books and film. But a thorough reading and watching of these narratives reveals a gap in the reported history of Hollywood’s relatively small but bulwark-like resistance to McCarthyism — namely, the participation of women.

Farmer’s testimony goes far in recovering that history, as does the testimony of Lillian Hellman, an American playwright who Maureen Corrigan of NPR called “the most famous American female playwright of the 20th century” and who Hellman’s biographer Alice Kessler-Harris called “a difficult woman.” Having come of age in the Roaring Twenties, Hellman drank, cursed, and eschewed monogamous relationships for open ones. She was also fiercely loyal to those she cared about, as evidenced in her HUAC letter: “[To] hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year’s fashions.” Though Hellman continued to write plays, she was subsequently blacklisted.

Her experiences in McCarthy-era Hollywood shook her deeply. When asked about that time in an interview from the seventies, Hellman lamented the lack of support among people she thought she could count on: “I wasn’t as shocked by McCarthy as by all the people who took no stand at all…I don’t remember one large figure coming to anybody’s aid. It’s funny. Bitter funny. And so often something else — in the case of Clifford Odets, for example, heart-breaking funny.”

It seems as if few people supported Farmer. Following her appearance in front of HUAC, Farmer secured two uncredited television roles and a one-episode appearance on the television show Summer Theater, starring Vincent Price. And then… nothing.

The blacklist began to dissolve in 1960, but by then Farmer would’ve been in her sixties, an “old woman” by Hollywood standards. In that 1977 interview with Lorraine Brown, she voices no regrets, however, for refusing to cooperate with HUAC. Instead she speaks proudly of her work in the theatre and on the screen, making no apologies for her political allegiances. Most of all she was proud of her work as a teacher: “During the time I was in [motion] pictures I had this studio. We taught a lot of people, and I think we influenced some.”

One student who was influenced by Farmer was Charles Elson, who said in a 1976 interview with Brown that he learned more from Farmer than any of his Ivy League professors: “Mary Virginia taught me a lot. I can’t even think that that much was drummed into me at Yale. I began to become aware of the need to have what the eye saw, express what the ear heard and to make it possible for the director to move as the director wanted the production to move without any interruptions.”

Brown asked Farmer in 1977 whether she could return to Farmer’s home to conduct a second interview, to discuss specifically her reasons for refusing to cooperate with McCarthy. The interview never happened; according to Farmer, her life’s work provided all the answers a curious historian should ever need. To say more, she said, “would just be repeating myself.”

The Sun Rises in the West flyer via the Library of Congress