The Mothman Economy

by Alison Stine

Photo: marada

In most ways, Point Pleasant, West Virginia, is no different from a string of other small towns set along the eastern Ohio River. It’s a town of four thousand in a county where the economy is dominated by coal companies and chemical manufacturing plants, and nineteen percent of the residents live below the poverty line.

On my first visit to the town a few years ago, I ran into Charles Humphreys of the Mason County Development Authority, who just happened to stroll up as I checked out a poster for a Neil Diamond cover band on the window of The Lowe Hotel. As we talked, nobody walked past us. No passersby wandered downtown or went into the historic hotel or the old theatre or the McDonald’s. But several people, some with out-of-state plates, drove up to a hulking, steel statue, planted on a traffic median on the main street. They wanted to take a picture. “Seven, ten people a day will take a picture with that statue,” Humphreys told me. “People drive into town just to see it.”

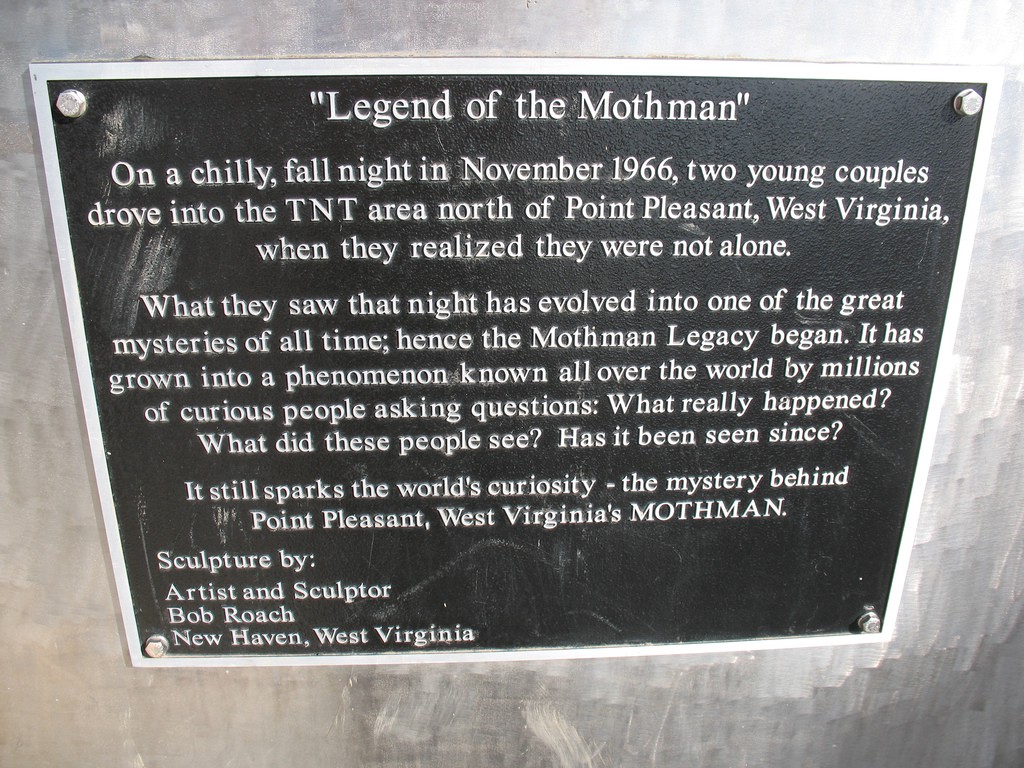

The statue is a large, silver creature with tattered wings, claws, and glowing red eyes. Its arms are wide, embracing nothing, and its mouth hangs open, full of long, sharp teeth. It looks out of place amid the empty storefronts and dusty sidewalks. It looks like it wants to eat the town. Sculpted by artist Bob Roach, the statue was unveiled in 2003 and has become the biggest tourist attraction in Point Pleasant: a statue to commemorate a legend and the town’s claim to fame, the monster who tried to save them.

Grave diggers saw it first: On November 12th, 1966, they claimed a huge, winged creature — too large to be a bird — swooped out of the trees and dived over them as they dug a fresh plot. Three days later, according to newspapers accounts, two young couples reported to the sheriff that a man with wings had followed their car. The couples had driven up to a place in Point Pleasant known as the TNT area, a former munitions manufacturing plant from WWII used to store explosives. The bunkers had been empty for years, buried under swampy land, making it a perfect place for teenagers to make out.

After the first creature sightings in 1966, more couples began driving up to the TNT area, hoping to see something extraordinary. Over the next few months, well into 1967, sightings of the creature accumulated, the details deepening. It was assumed to be male; he sometimes attacked cars, like a peacock; his eyes reflected flashlights and glowed. Over a hundred people called the sheriff to report sightings in their small town of this strange, flying creature that was eventually dubbed the “Mothman,” reportedly in homage to the Killer Moth, a Batman villain who was popular at the time.

On December 15th, 1967, a little over a year after the first Mothman sightings, the Silver Bridge, which connected Point Pleasant to Ohio, collapsed. An eye-bar snapped, and the bridge, packed with holiday traffic, went down in less than a minute, cars sliding into the icy Ohio. Many people were trapped in their vehicles; some drowned, while others died of hypothermia. In total, forty-six people died. Two bodies were never recovered.

Over the years, the Mothman began to be thought of by some as a harbinger, an idea which was cemented by freelance reporter and pulp writer John Keel’s 1975 book, The Mothman Prophecies. In the book, Keel recounts residents’ prophetic dreams and supposed messages leading up to the Silver Bridge collapse — messages, reportedly, from the Mothman, who was never seen again after the accident.

Mothman’s popularity has only grown in recent years, despite — or maybe because of — the creature’s absence. Keel’s book, the first of many about the creature, was turned into a movie, The Mothman Prophecies, starring Richard Gere, which was filmed on location in Point Pleasant and premiered worldwide in 2002. That same year, the Mothman Festival began. It was followed by the statue, in 2003, and the Mothman Museum and Research Center two years later.

I attended the twelfth annual Mothman Festival last year, on its final day, a rainy Sunday after the crowd of thousands had dwindled to a scattered hundred or so. The Saturday of the festival is normally the single biggest moneymaking day of the year for Point Pleasant: Bigger than Christmas, it’s the only weekend the historic Lowe Hotel is full, along with hotels in Gallipolis and nearby Hurricane and Ripley. But there was plenty of parking on the street when I visited, and several blocks of abandoned stores to walk past before seeing any people at all. “Closed” or “for rent” signs had been propped in windows, dark and coated in dust. A Mothman roamed around the street in giant wings and a bug-eyed headpiece which obscured his sight; he was accompanied by a teenage boy who kept steering him away from passersby.

The old movie theatre looked abandoned from the outside, but the door was held open by a brick. I passed through the lobby, where a framed picture of a beauty queen hung on the wall, the Pepsi-sponsored snack bar had been abandoned, and the red shag carpeting puffed up dust. Someone was speaking quietly in the auditorium. I entered, stood at the back. A dozen people filled the seats, mostly at the front. A man paced on the stage. He looked large, his arms as strong as the Mothman statue. He spoke confidently about Dog-Man, a creature I had never heard of, but there was a blurry slide of a furred thing. The man — a cryptozoologist — told the crowd that Dog-Man must be a carnivore because “an animal that size is gonna need meat.” Nobody laughed at the Dog Man talk. Nobody made fun. Audience members took notes; I took notes. I left before the house lights came on and the questions began. Some of the other lectures that weekend included such topics as Big Foot, “Murder Victim Ghosts,” and “Mothmen Abroad.”

Down the street, traffic had been re-directed by barricades. Booths clustered around the Mothman statue, mostly white tents where paranormal books and buttons and posters were for sale, while food trucks sold Mothman cookies with Red Hots for eyes.

The Mothman Museum and Research Center moved into new digs last year, a former Navy surplus store just to the side of the statue. The museum houses monster fan art, souvenirs, and memorabilia from The Mothman Prophecies: the plaid blanket that warmed Debra Messing’s lap, the wool overcoat that Richard Gere wore, autographed pictures of the movie stars, pages from the script, a paint can used in the film. A gift shop takes up the front of the museum, filled with mugs, rubber Mothmen, “Mothman Hunting Permits.” There are mannequins dressed as Men in Black, a stuffed owl. A documentary plays on repeat. Jeremy, who staffs the museum most days, was humble about what Mothman has done for the town. “I’m thrilled this is here,” he said, gesturing around the museum. A Mothman model hung by a thread above the cash register, swooping above Jeremy’s head like those grave diggers said the creature had done, all those years ago. “I wouldn’t have a job without this.”

Photo: Jason W.

It poured after I left the museum, so I sought shelter under a tent that housed an author hawking a self-published supernatural YA novel. She smiled at me hopefully when I ducked under the tent, and rearranged her display of glossy books. I smiled and, embarrassed not to buy a book, embarrassed not to want to, looked away. I spent a long time at a booth run by Eerie Eric, an artist who sold his own illustrated comic books, postcards, T-shirts of Bigfoot and other spooky things. There were more tents set up along the river, including one for the Miss Mothman pageant. The queen and princesses had already been crowned by the time I made it to the river, and the girls sat on folding chairs eating BBQ “Bat Wings” in their prom dresses and crowns. The girls’ handler frowned at me when I took a picture.

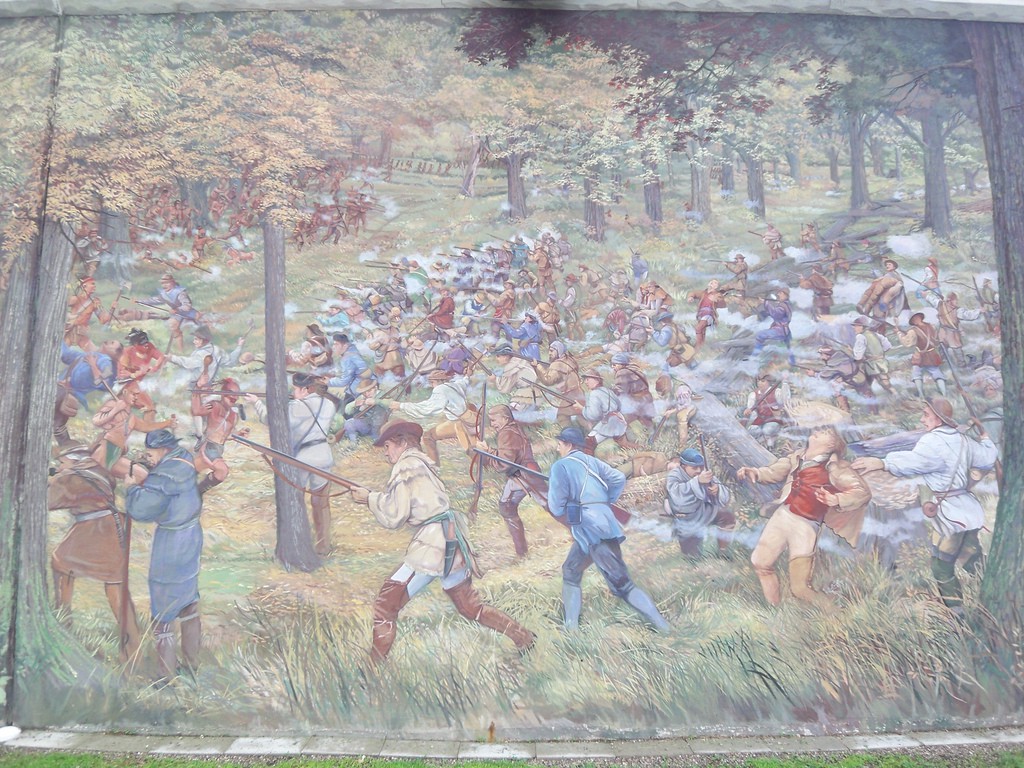

There was a new stage by the river in Point Pleasant, built mostly for a small summer music festival. The giant floodwalls banking the river have been painted with a mural depicting the Battle of Point Pleasant, a 1774 fight between the Virginia militia and Shawnee and Mingo tribes. Humphreys, of the development authority, told me that the murals and stage were part of the planned revitalization of downtown. During the Mothman festival, a hardcore band played, though the bleachers built into the hillside sat empty and damp. A few children danced, swatting each other with inflatable aliens.

The Iron Gate Grille at the end of Main Street had closed by four that afternoon (it was a Sunday, after all), but the owners let me inside. Outside, the marquee read, “Welcome Mothman” with a shaky image one of the owners had drawn. Inside, most of the lights had been turned off and the owners drank Bud Lights at the bar. The dim dining room was decorated with plastic ivy, leatherette booths, and gold-studded chairs. One of the owners, a woman in her forties who looked like she had stepped out of a teen movie dream — golden-feathered hair, cut-off shorts — said she had never left Point Pleasant, except for vacation. She had never had a reason. “Everything I need is here,” she said, looking around.

The silence and the darkness of the bar was a shock after the festival. The sun had come out on the street after a long break, and I had taken stock of the crowd walking back down the block: a mix of locals, families with children looking for something to do, people in their twenties from Columbus and Cleveland who maybe came for the novelty, maybe to have a laugh in Appalachia — but even so, they wandered, wide-eyed, taking pictures, like everyone else, telling and hearing the stories like everyone else.

The Iron Gate Grille owners told me it was their best weekend all year: They had served thousands of people and were so exhausted that they were going to go home early. The woman downed the rest of her beer in a gulp, then pitched the plastic cup in the trash. The man had already finished his, and had gone to the back of the restaurant. She switched the bar light off, but smiled and said, “Stay here as long as you like.”

Photo: David Becher