Incorrigible Sin

The story of a seventeenth-century fornication trial in Massachusetts Bay

One of the worst nights of Sarah Crouch’s life began with an innocent request. Her mother asked her to go out into the fields and fetch Thomas Jones for supper. It was a quiet June evening during the pea harvest of 1668, and the sun had just begun to set over the Crouch family’s homestead in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Though Crouch, 20, had just woken from an early-evening nap, she gladly agreed to wrangle him in. Jones, who worked for her father, was a common presence in their household. Crouch liked him. As to how well, it depended on whom one asked.

Charlestown’s lively gossip mill buzzed with rumors of the couple’s intimacy — likely based upon the claim made by the Crouches’ neighbors, Joseph Bacheler and Paul Wilson, that they had seen Crouch in bed with Jones at the home of Theophilus Marches during the “last election day at Boston.” Another rumor claimed that Crouch and the twenty-three-year-old bricklayer were not only intimate but also secretly engaged.

This latter rumor was of particular interest to another regular visitor to the Crouch homestead: Middlesex County’s own resident Lothario, Christopher Grant, Jr. Crouch knew Grant, 24, through mutual friends. That same evening, he and his brother, Joshua, had dropped by for an unannounced visit. As Crouch made her way outside to find Jones, Christopher rushed toward Crouch’s mother. “Might I go forth with her,” he asked; to which she responded, “As long as you stay within hearing.”

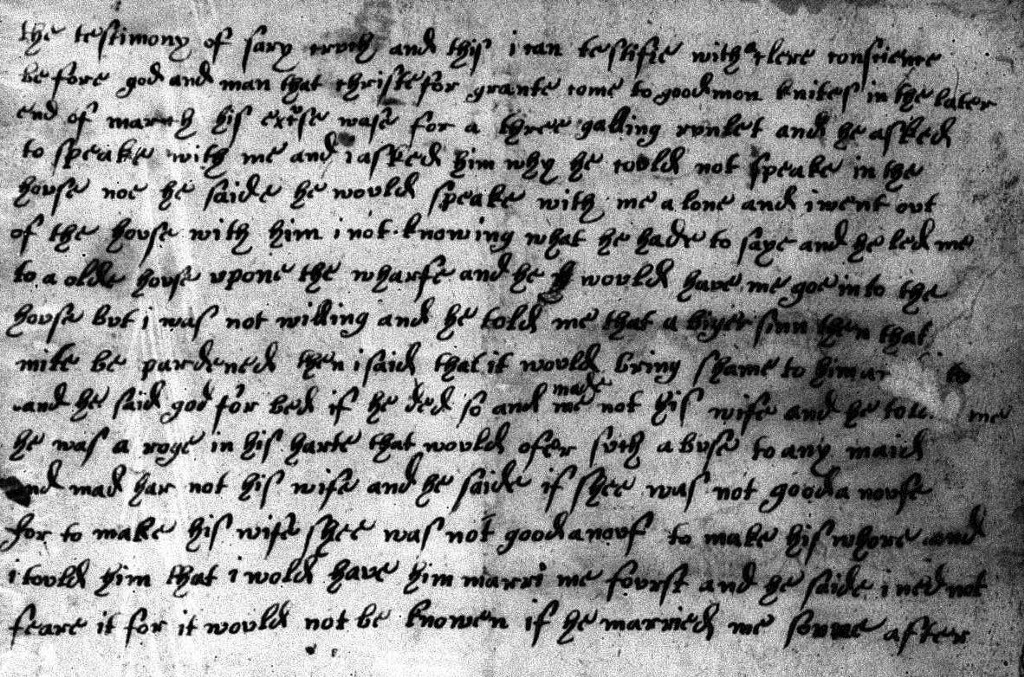

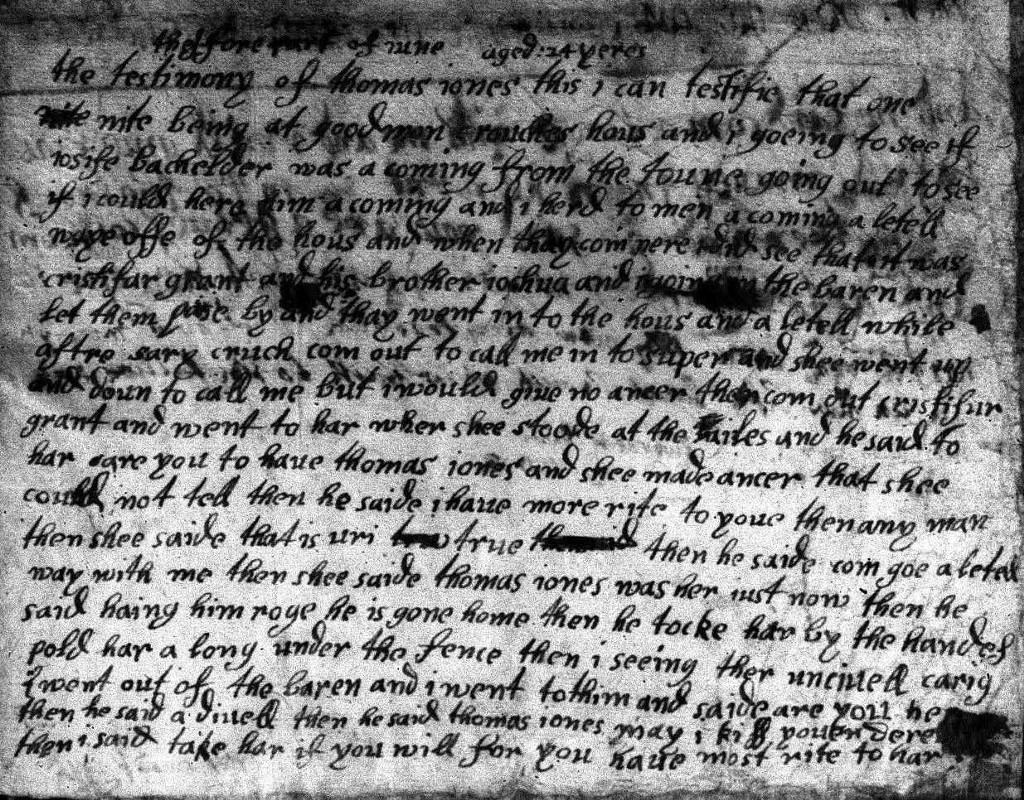

Crouch’s account of the evening, written one year later as a court deposition, does not reveal her thoughts on Grant’s insistence, nor does it explain the excuse he had given to her parents to explain his presence at their house that evening. It is very likely, however, that she knew Grant’s intentions. In her own words, he had “made use” of her body at least twice over the past few months. The first of these encounters occurred on March 28 in “an olde house upon the wharfe.” There, Grant seduced her with a Falstaffian marriage proposal. “If she was not good enough to make her his wife she was not good enough to make his whore,” he said. When Sarah responded that they should wait, “he said I need not fear for it would not be known if he married me soon after.” Amid a second sexual encounter in April, Crouch had told Grant that she feared the first had resulted in a pregnancy. “How long afore [you’ve] had the sines of a maid,” Grant asked her. “Three days before the first time [you’d] had to do with me,” she responded.

Grant, desiring either sex or updates on her condition, and angered by the unconfirmed rumor of her engagement to Jones, kept close to her in the months to follow. This June night would prove no different. Sarah soon trekked out into her father’s fields to search for her rumored fiancée, trailed by the “heartless rogue” who may have gotten her pregnant.

In the mid-seventeenth century, Massachusetts Bay found itself amid a spiritual identity crisis. Many first- and second-generation settlers believed their children and grandchildren had lost touch with the colony’s original mission. This new generation was materialistic and greedy. Worse, it was becoming increasingly sexual. Though pregnancies out of wedlock were far rarer in Massachusetts Bay than in England or its other colonies, records show that by 1665, County Court officials saw premarital sex as “a shameful Sin, much increasing amongst us.”

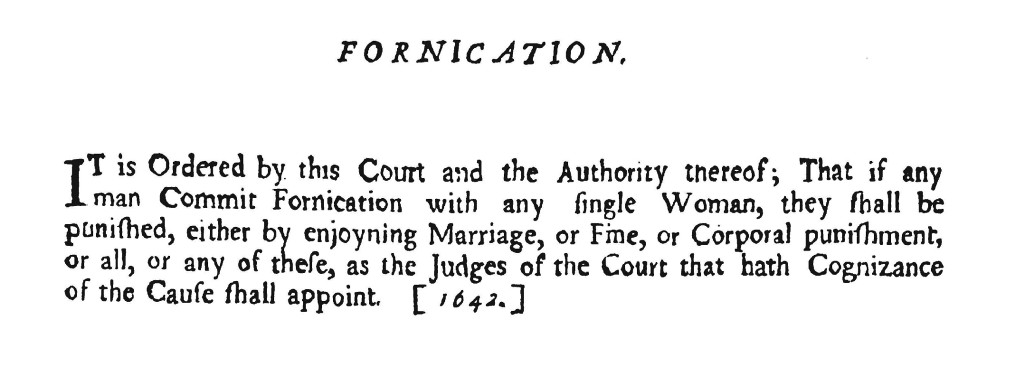

Contrary to modern perception, Puritans were not ashamed of sex itself. As the historian Edmund Morgan put it, the New England Clergy, “the most Puritanical of the Puritans,” believed that so long as a healthy sex life did not interfere with a married couple’s relationship with God, they were welcome, and indeed encouraged, to discuss and explore its boundaries. Premarital sex, however, remained illegal. Massachusetts’ first published fornication law, written in 1642, stated that guilty parties should be “punished, either by enjoyning Marriage, or Fine, or [whipping].” Two decades later, they added excommunication to the list. When caught in the act, or when exposed through pregnancy, “fornicators” were indicted and scheduled to appear before a group of magistrates during one of four annual meetings of a local county court. The historian Roger Thompson reports roughly 125 of these trials occurred between 1649 and 1680. Most were cut and dry. The accused mother, if pregnant, named a father. Magistrates then doled out punishments and made provisions for the resultant child.

Cases involving disputed paternity were far more complicated. Such was the case with Sarah Crouch and Christopher Grant Jr. The Crouch v. Grant case file, found in Folio 52 of the Middlesex County Court Records, contains 26 documents. Dated Feb. 2, 1669, these papers — which recount everything from rape allegations to a late-night orgy — tell the story of a love triangle involving the exact sort of rebellious twenty-somethings whom elderly colonists resented. Crouch came from subversive stock. One year earlier, the Charlestown Church had formally censured her father for “the scandalous sin of Drunkness” and his “not manifesting repentance for it.” Grant too came from a controversial family. Before his own indictment for fornication, the Court had already convicted two of his sisters for the same crime.

Colonial courts relied heavily upon written depositions. Defendants and witnesses prepared these documents in the months before proceedings began. Shortly after her indictment, Crouch could expect everyone she knew — her family, her neighbors, her enemies — to commit to paper their private thoughts about her, her reputation, and her behavior. Through these accounts, one can begin to imagine what it must have felt like to be young, libidinous, and malcontented while living in seventeenth-century New England.

Like thousands of other ordinary colonists, most of Sarah Crouch’s life exists within an elementary outline culled from official records: birth, baptism, marriage, death. Church logs suggest she was strong-willed and impetuous. Officials lamented that at the time of her indictment, Crouch was not “in full communion.” Although she had been baptized as an infant, she had yet to fully devote herself to the Church, nor had she shown any desire to do so.

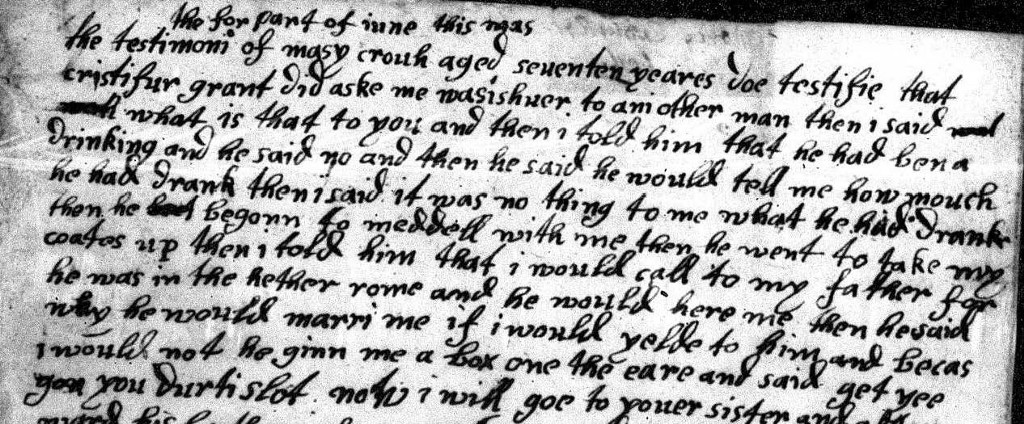

Still, as Crouch went to trial, she had support. Depositions written in her defense — principally those by Thomas Jones and her sister, Mary — suggest a coordinated effort. As colonial courts only met four times a year, she and her friends had months to get their stories straight. Crouch’s pregnancy made it impossible to deny guilt. She therefore devoted her efforts to proving Grant, rather than Thomas Jones, had fathered her child. She and her peers focused on the man’s persistent and at times violent history with women. Crouch’s sister suggested he had once propositioned her by promising to marry her if she had consented to sex. When she refused, Grant had attempted to “meddell” with her, allegedly taking her “coates up,” boxing one of her ears, and calling her a “dirty slot.”

Though it had been the first of two consensual encounters that had resulted in pregnancy, Crouch committed the bulk of her testimony to a third and comparably violent run-in with Grant: the night he followed her into her father’s fields to find Jones. According to Crouch, he immediately revealed himself as a jealous mess. The rumor about her engagement to Jones — which she never confirmed in her own testimony — had sent him into a fury. One witness claimed that a few weeks earlier, Grant had been so worked up over it that he confronted Sarah’s father, who confessed ignorance. That night in June, Grant’s frustration boiled over.

“I have more right to you than he does,” Grant told Crouch. “[Jones] can maintenance you about as well as a dirt dauber.”

Crouch testified that things soon turned violent. “He took me by my [two] hands,” she wrote, “[and pulled] me along and under the fence.” There, Grant allegedly raped her.

At some point, the pair was interrupted by none other than Thomas Jones. He had been hiding in a barn within eye and earshot of the whole affair. Per his own brief testimony — a deposition that mimicked Crouch’s nearly to the word — he had been searching for a friend earlier that evening when he had heard the Grant brothers enter the Crouch family property. By the time Crouch had begun to call for him, he had already taken his place in the barn. It is not clear whether Jones knew of Crouch’s history with Grant. Regardless, he had seen enough.

“Henceforth,” Jones told Crouch, “I will have nothing to say to you anymore.”

Grant took the opportunity to rub salt in Jones’ wound.

“Shall I kiss your garle, Thomas?”

“You have more right to her than I have,” Jones replied. “Take her if you will.”

What happened next eludes the historical record. The story picks up a few weeks later when Crouch confirmed to Grant she was indeed pregnant. She claimed that they spent the next few weeks weighing their options. Finally, Grant put his foot down. He told her he would only marry her if she ended the pregnancy. Crouch refused, and Grant failed to propose.

Heading into trial, Grant faced an uphill battle. The burden of proof in Puritan paternity cases typically fell on would-be fathers. Most magistrates reasoned it was a greater sin to force an infant and its mother into pecuniary uncertainty than it was to compel a man to financially support someone else’s child. Defendants needed to provide overwhelming exculpatory evidence, otherwise the Court would deem the accused legally responsible “notwithstanding his denial.”

Grant put together a much better case than most. Numerous friends, neighbors, and family members wrote depositions in his defense. Just as Crouch and Jones seem to have straightened their stories before committing them to paper, it is clear Grant conducted his own private investigation into what, exactly, people were saying about the events leading up to Sarah’s pregnancy. In his testimony, he urged the magistrates to pay close attention to the depositions written by his brothers; another one penned by a man named Samuel Church; and, especially, the testimony of a woman named Sarah Largin.

These documents tell a radically different story from the one narrated by Crouch and Jones. Not only did Grant deny any intimacy with Crouch, but he and his supporters also hinted at conspiracy. Grant’s brother, Joseph, testified that Crouch was obsessed with Christopher, who “gave her no cause to love him.” Even more pointedly, Church implied that Crouch knew she was pregnant and chose to pin the paternity on Grant because he was “rich at the time” and thereby better suited to support her child than was Thomas Jones (presumably the true father).

Charlestown resident Ursula Cole claimed that shortly after Crouch’s pregnancy became public knowledge, Jones had described to her a recent encounter with Crouch, in which she implied Jones was the father. “[Jones] told [Crouch] that she showeth as if she [was] bigg with childe,” Cole wrote, “and [Crouch] answered [if I am with child] you shall provide blanketts for it.” Jones then allegedly assured Crouch if she were pregnant with his baby, he would do his part to support the child. Cole added that Jones even bought her a symbolic blanket. By July of 1668 — one month after the confrontation outside the Crouch home — Cole had heard that the couple had split up. She said Crouch told her that Jones had dumped her because he was “jealous of Christopher Grant,” even though “he had no occasion at all” to feel threatened.

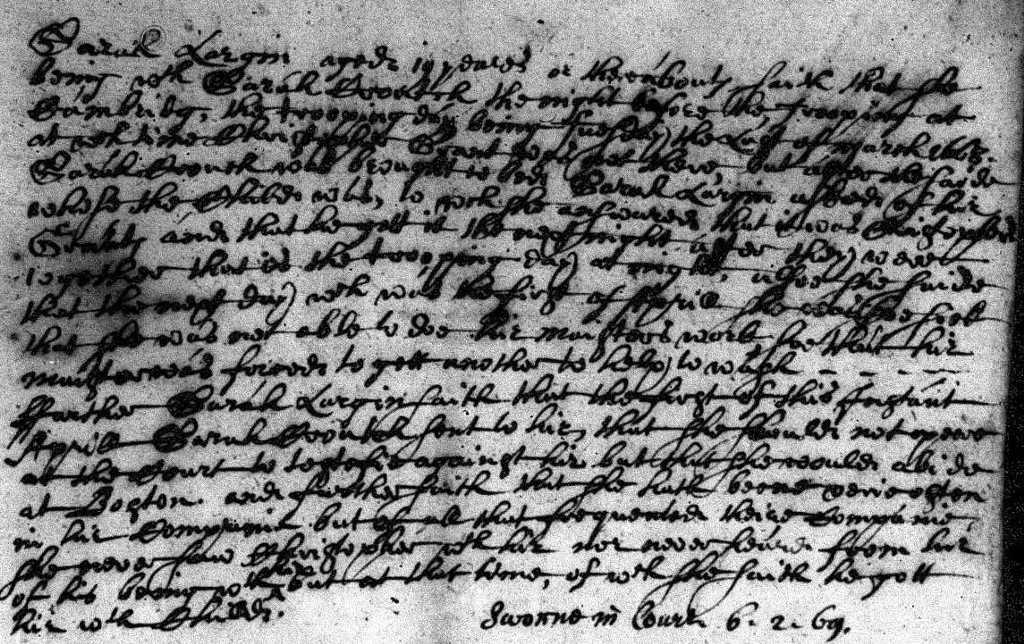

Largin claimed she was with Crouch during the alleged night of conception “at which time Christopher was not there.” Months later, when Largin noticed Crouch’s belly, she asked her about the identity of the father. Crouch quickly named Grant. Soon thereafter, Largin confronted her on the inconsistencies. Crouch’s response to this confrontation remains lost, but she clearly panicked. According to Largin, a few weeks before trial, Crouch “sent to her that she should not appear at Court to testify against her but that she should abide at Boston.” Largin concluded her deposition by admitting that although she had seen Crouch “very often” in Grant’s company, “she never saw Christopher with her [around the time] she saith he got her with child.”

Largin’s testimony carried a great deal of weight, not only because she was close to both parties, but because she herself had been implicated in salacious rumors about Crouch. Few in Massachusetts knew more about her sex life. Nowhere was this more evident than in the provocative testimony of Crouch’s employer, John Knight.

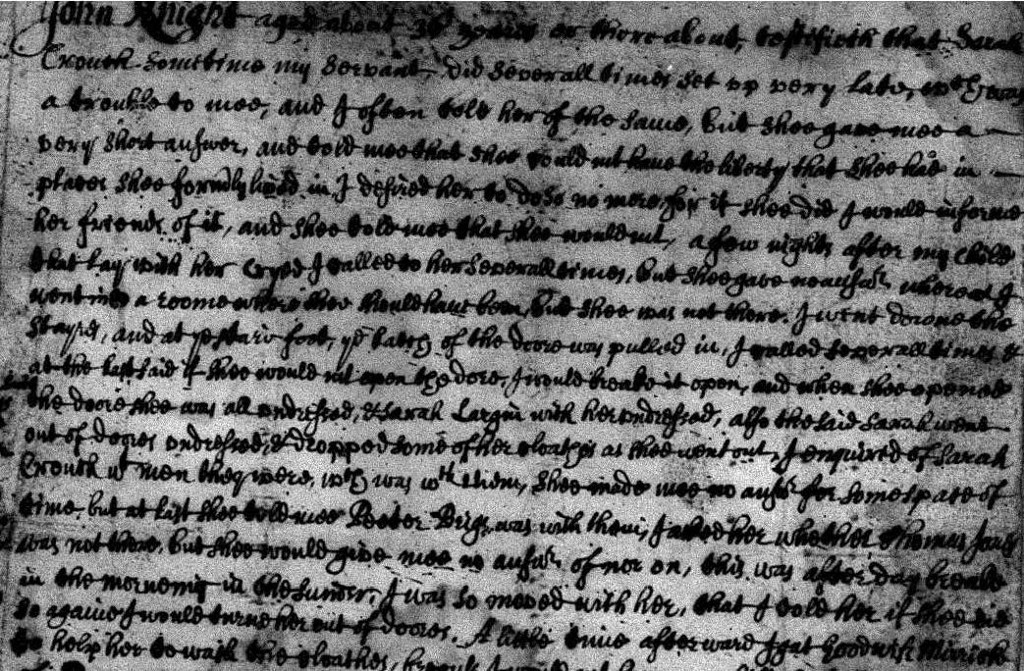

Knight, a widower with multiple young children, made his living building and repairing barrels in nearby Watertown. He employed a handful of part-time servants and maids, and his testimony suggests Crouch often took care of Knight’s infant as the cooper slept. This work left Crouch unsupervised in late evenings and early mornings, of which Knight claimed she took full advantage. “My servant did severall times stay up veri late [causing trouble] to mee,” he wrote in his deposition. “I Often told her of the same, but she gave me a veri short answer and told me that she would not [give up] the liberty that she [had] in places she formally lived in.”

One evening, he awoke to the sound of his child bawling. He called to Crouch several times, “but she gave no answer.” Vexed, Knight meandered sleepily into his child’s room only to find the baby unattended. Crouch’s quarters were empty, but he soon heard a series of noises coming from a room or a closet near the stairwell. Assuming Crouch was inside, he yelled “that if Shee would not open the door, [he] would break it open.” The doors unlatched, and out came “[Sarah Crouch] all undressed [and] Sarah Largin with her undressed.” Largin took off through the front door, dropping “some of her clothes as she went out.” Knight cornered Crouch and inquired about any men who might have been in her company before his arrival. “She made mee no answer for some span of time,” he wrote, “but at last Shee told me Peter Brigs [another local twenty-something] was with them.” Apparently aware of Crouch’s involvement with Thomas Jones, Knight asked if “Jones was not there” as well. When Crouch failed to respond, he became “so mad with her” he threatened to “turn her out of doors.”

A few days later, the cooper hired an extra servant — a woman named Goody Mirrick — to help him with his laundry. He left Mirrick and Crouch alone as he ran an errand in town. When he returned that afternoon, he found Mirrick “alone and the childe crying.” He asked her where his “maid was.” Mirrick, begging forgiveness, answered that Crouch was not in the house. Knight searched his property, and again came upon a closed door latched shut, behind which he found Crouch and Largin in a state of undress, this time with Brigs and another local man named Michael Tandy.

Knight’s story supported two major facets of Grant’s defense. First, it confirmed Crouch was sexually adventurous. Second, it demonstrated her relationship with Jones had become so well known in Charlestown that even Knight, a grown man with no direct ties to her peer group, knew to ask if Jones were involved in the closet orgy. This, along with Crouch’s neighbors’ testimony that they had caught her in bed with Jones shortly before her pregnancy, greatly complicated the paternity issue. Was this unflattering (but largely hearsay) testimony enough to earn Grant a rare and unlikely acquittal?

Colonial court records are cruel to curious readers. Their depositions resemble proper narratives, as they recount interesting events from multiple points of view, often richly and in great detail. Yet these records aren’t narratives, nor are they inherently rooted in the truth. They gleefully rebuff Chekov’s gun. They heighten anticipation through made-for-cinema twists and turns, without a single guarantee of a satisfying resolution.

The Crouch vs. Grant case file contains no record of a final judgment from Court magistrates, but subsequent Middlesex County Court files shed light on the result. On April 15, 1669, Grant’s parents wrote a letter to the Court that implied the trial had ended in his conviction. In it, they lamented that their son was “Sentenced to the house of corrections.” But he never actually made it there. At some point between the trial and their petition, “[Grant] maid his Escape.” Court magistrates had also sentenced Christopher to a public whipping. According to his parents, the prospect of this punishment had caused him to flee town.

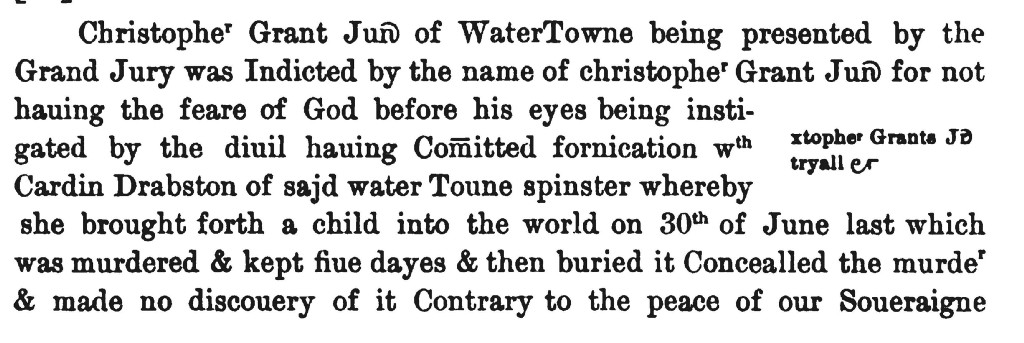

By 1677, records show Grant was back in Watertown, where he once again put himself at odds with the law. That year, he became involved with Cardin Drabston, one of his father’s servants, and she became pregnant. A grand jury in Watertown indicted Grant for fornication in 1678, but the charges did not stop there. “Drabston,” the account goes on to say, “brought forth a child into the world on the 30th of June last, which was murdered & kept five dayes & then buried.” Though the magistrates did not implicate Grant in the infanticide, they did charge him with concealing it. He pled not guilty, and officials soon acquitted him of the most serious charges — though it remains likely he suffered another public whipping. Grant died in 1692, just short of his fiftieth birthday.

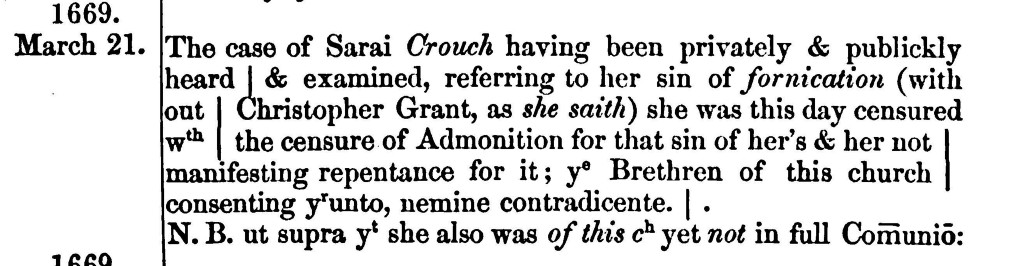

As for Crouch, the years immediately following her indictment were equally fraught with drama. A year removed from the birth of her first child, she again faced charges of fornication after a second pregnancy came to light. In the Charlestown Church Records, a listing exists, dated March 13, 1670. It reads: “This church, having heard the case of Sarai Crouch, referring to her sin of fornication With Thomas Jones, voted that she should be excomunicated for [persisting] so impenitently, incorrigibly in sin, while under censure for that committed March 21. 1669.” This time, Crouch did not refute that Jones was the father. Though the Church planned to excommunicate her, it decided to defer final judgment until after the delivery of her child. Ultimately, it left the door open for her return to the congregation, assuming she properly repented. This likely had something to do with a subsequent file, which can also still be found in the records of the Middlesex County Court.

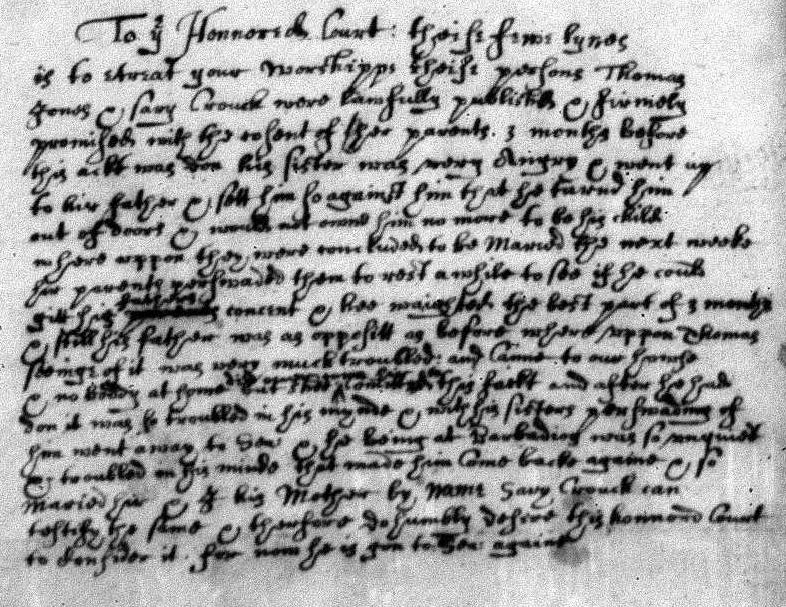

In an undated petition, likely written before Crouch’s April 1670 court date, her parents argued that her second fornication offense occurred amid extenuating circumstances. She and Jones “were lawfully published and firmly promised with the consent of [her] parents 3 months before this act was done.” The match had apparently upset Jones’s sister. She was “very angry and went up to [their] father and set him so against [Thomas] that he turned him out of doors and would not grant him no more to be his child.” The Crouch family, hoping to obtain a proper blessing, had advised the lovers to wait for approval before committing to marriage. Three months later, Jones’s father remained unrelenting. “Thomas hearing of it was much troubled and came to our house,” wrote Crouch’s parents, but nobody “was there but Sarah.” During this time, Jones “did overcome her to commit this act and after he had done it he was so troubled in his mind, and with his sister persuading him, he went away to sea.” After months working in Barbados, Jones was “so anguished” he decided to come back and marry Crouch with or without his parents’ blessing. The pair married and had five children over the next nine years.

After Jones died in 1679, Crouch married a man named Thomas Stanford. Together, they had at least nine additional children, securing her position as an early colonial ancestor for thousands of future Americans. More than a happy ending to a life otherwise defined by trauma, Sarah Crouch’s productive marriages offer an alternative view on the nature of our national origins. Americans with deep roots in Massachusetts descend not only from the morally righteous denizens of John Winthrop’s famed “city upon a hill,” but also from flawed and ordinary people — many of whom were unrepentantly themselves and often paid the price for it.

Daniel Crown writes about history and books.

A Note on Sources

The material in this article is drawn and quoted directly from original depositions found in Folio 52 of the Middlesex County Court Records (except where noted). I obtained these documents on microfilm through FamilySearch.org. I’d like to thank Elizabeth Bouvier, Head of Archives at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, for helping me isolate the files I needed. I first encountered the story of Crouch v. Grant through a brief mention in the essay “Puritans and Sex” by Edmund Morgan and later again in Roger Thompson’s Sex in Middlesex: Popular Mores in Massachusetts County, 1649–1699. Though these works served as roadmaps to key sources, I referred only to my own transcriptions of the original colonial-era chicken scratch when piecing together my narrative. In the process, I found unpublished testimony — most notably from Sarah Largin and Samuel Church — which provides new insight into how Sarah Crouch spent the months leading up to her trial, as well as the circumstances surrounding her marriage to Thomas Jones. Other primary sources included The Records of the Court of Assistants of Massachusetts Bay, The Record-Book of the First Church in Charlestown, and The General Laws and Liberties of the Massachusetts Colony: Revised & Reprinted.