The Deactivation of the American Worker

The American employee is increasingly no longer an employee at all.

by Carter Maness

Last November, at the offices of Gawker Media, a series of editors were summoned, one by one, via direct message on Slack, the company’s inner-office chat and collaboration platform, to a conference room. The executive managing editor wanted a word, they were told. Workers who hadn’t been messaged began to notice that the names of the summoned, ever present on their contact lists, were going dim and then disappearing from Slack. “I had no idea layoffs were coming — none of us did,” a former member of the editorial staff told me. “After I returned to my desk, my Slack account had been disabled. I guess the fear was that employees who had been let go would spread word to their coworkers. But it’s Gawker after all, a place where secrets, lies and even closed-door layoffs eventually come into the light.”

There was no official announcement, memo, or really any communication to explain what was happening until after the layoffs had been completed. The job terminations, like the bulk of the media outlet’s work, were first experienced by most Gawker employees in digital, rather than physical space. Deleting the accounts was merely the company’s attempt to assert control of its office space, and Slack’s role in the layoffs simply exemplified where work was actually being done; it also serves as an indicator of, for many employees in the coming years, where it will end.

Slack isn’t down. You’ve been fired.

— @fmanjoo

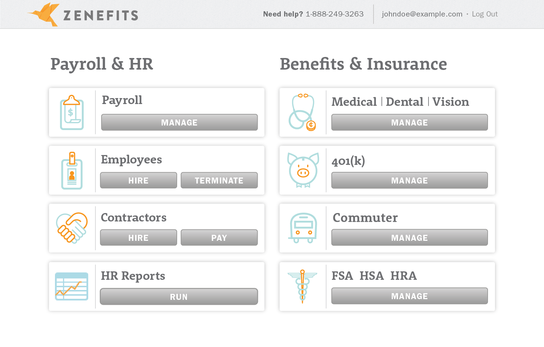

On Twitter, the deactivated Slack account became a way to demonstrate fear of being laid off. “Is my Slack down or am I fired?” is a good joke in a Freudian sense because it reveals a deeper truth about how tenuous jobs have become. Before, a worker might arrive to the office to find her keycard no longer works, or their desk contents boxed and ready, a security guard waiting to escort them back to the parking lot. It’s a messy image, bad for morale and, now, easily avoided by quietly deleting a worker’s access to their work and colleagues. As the open office, with its cacophonous lack of privacy and false promise of improved collaboration, is replaced by a virtual one running on labor and benefits platforms like Slack and Zenefits (lol), the American employee is increasingly no longer an employee at all, but someone granted the privilege to work by a network administrator, an opportunity just as easily revoked.

Job security, a pillar of American business as far back as the late nineteenth century, began to erode in the nineteen-seventies as a confluence of globalization, weakened unions, and soaring executive bonuses tilted the scales toward the wealthy and powerful. The eighties saw the rise of consulting firms which specialized in layoffs; armed with new “efficiency strategies,” these companies advised their clients on how to become more profitable and, in some cases, even handled job terminations for them, neatly coinciding with the Reagan-era rise in layoffs. Job terminations became enough of a trend that the New York Times ran a recurring column, “Layoffs This Week.”

If the seventies embraced globalized manufacturing, which relied on overseas factories with their own staffs, the nineties saw an explosion of foreign labor as work could be done offshore for a fraction of the cost. This led to a systematic reorganization in corporate America where some companies, once teeming with mega-departments filled with lifelong employees, were downsized to “essential personnel,” often the very people tasked with managing the outsourced labor replacing their colleagues. In July 1993, IBM commenced the largest mass termination in history, ending sixty thousand jobs at once, topping Sears-Roebuck, who terminated fifty thousand jobs earlier that year. The Clinton era also saw the rise of “going postal,” as gun violence in American workplaces became a trend. One could maybe attribute this, in a roundabout way, to the loss of job security due to globalization and automation.

The nineties, as you’ve no doubt been reminded, were an economic boom time in America, but as the scale of many companies grew along with their profits, so did the scope of their layoffs. Bill Clinton left office and, barely two months later, the economy began to collapse. Other than the U.S. Postal Service, Boeing (aviation), Ford (automotive), Lucent (telecommunications) and Kmart (a company which now apparently sells goods from other bankrupt companies) brought the largest mass layoffs of the early aughts. Several years later, another wave occurred, the tsunami generated by an earthquake of economic catastrophe. During the 2008 financial crisis, Citigroup dropped fifty thousand employees. Bank of America followed with thirty thousand in 2011. In 2009, General Motors had to lay off forty-seven thousand in the biggest autoworker termination in history.

These are unseemly numbers, figures best avoided by slowly cutting jobs over weeks, months, even years. Stealth layoffs are how corporations terminate now. They’ve been common since 2008 as banks, learning from their conference room bloodbaths in the eighties, kept things quiet by chipping away rather than slaughtering their workforce; even if cuts result in the same number of jobs lost, stealth layoffs don’t elicit the type of public relations hit which comes from a fifty thousand-person bloodlet. Yahoo is a master of this method; it’s been keeping its employees in a state of perma-terror for nearly a decade, even while still engaging in the occasional throwback layoff as when it shuttered its stable of ‘digital magazines’ last week.

By 2012, the last available year of mass layoff data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (because the program itself was terminated by President Obama as part of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act), there were over seventeen thousand events where more than fifty people were laid off at once. Many of these, given their volume and the physical layout of offices, which tended to favor clustering employees in open arrangements without privacy, took place in conference rooms (often in batches; safe go here, terminated over there) or via email.

As the nineties saw the rise of virtual offices based around email and webpages, workers transitioned to a scenario where their email addresses became more than the replacement for a physical mailbox. A corporate job became official when you received your email address: Your first message introduced yourself to coworkers with a company-wide blast; your last was a goodbye note to those same people. Then your email history, and you, were erased. In between, perhaps, thousands of messages: projects in various phases of completion, proof of work, meeting notes. Those, more than your presence in a cubicle, were the evidence of your employment and subsequent value to a company.

Our way of laying off now reflects our modes of communication. The story of a Florida restaurant canning its entire staff via text message brought out the Carrie Bradshaw Post-it references, but no one was surprised at the delivery method. Zirtual, a virtual assistant company, announced it was folding in an overnight mass email with no warning. George Zimmer, of Men’s Warehouse guarantees and the company’s founder, chairman, spokesperson, essentially found out he was fired via email. Rafa Benítez, the coach of Real Madrid (a soccer team of some sort?), found out he’d been replaced when the owner of the team announced it in a press conference. A Twitter employee received the news after a Yahoo notification on his phone sent him to a tweet from Jack Dorsey, the company’s CEO, announcing eight percent of its workforce was cut.

The business communication application Slack appears to be another email-killer, yet its combination of archived conversation and files, syncing among multiple devices, and search that actually works carries the makings of a more transformative office technology, one that’s changing both the way workers collaborate and how they are eventually laid off. Like email, Slack rewards active employees who assert their presence through how frequently they post. It provides a simple platform for group communication, something email claims to do when it’s only really creating multi-threaded headaches. The company’s self-professed goal is to make work easier as a result of improving the efficiency of a team, a task accomplished by turning departments into hashtagged channels and maintaining a transparent record of everything that happens within them.

For many workers — in narrow but highly indicative industries — Slack has already shifted the idea of physical office space into an idealized digital version of itself. And if venture capital has anything to say about it, the rest of the world isn’t far behind. Rather than actual rooms, employees congregate in these channels; they gossip over direct messages and build office-specific languages using emoji. Slack played its role in the Gawker layoffs because it was both the organization’s primary mode of communication and office space; terminations have transitioned from clusters of desks to digital communities, malleable teams with a built-in institutional memory that’s unbeholden to physical space.

A worker laid off by losing her access to #sadmarketing will be replaced by someone who not only occupies her actual desk but has access to every document she’s uploaded, every meeting she attended and even the pithy asides about that very meeting; all the gifs and in-jokes and Hamilton sdlfkjsd, sure, but also the contacts relevant to the job, the advantage of being able to instantly catch-up because the information has been elegantly archived and arranged for future workers. Employees whose self-worth depends on their unique knowledge of the organization no longer have that benefit. Instead of a disorganized series of private inboxes, there is now a valuable public record. The job is a body of work; the person doing it is more interchangeable than ever.

A layoff occurs when a worker loses access to a communication platform. This structure also applies to the increasingly large class of independent contractors who, because their app-based companies refuse to acknowledge their status as actual employees, experience termination through deactivation. An Uber driver who rates poorly — the bar for dismissal is a secret but is thought to be a rating of around 4.6 out of five — could open the app to find his privileges revoked without explanation. The platform which enables him to do his job carries no guarantee, and, as a worker, his rights are essentially that of a freelancer.

Is getting kicked off a service the same as being laid off? As Uber drivers push to unionize in Washington and California, the company remains hilariously obtuse when it comes to its relationship with drivers. “Your account has been flagged a final time for having significantly more cancellations than other partners,” read one driver’s reason for deactivation. “We believe Uber may not be the right lead generation tool for you. We wish you the best, but we have decided to discontinue our partnership.”

A cursory exploration into exactly how big the gig economy has become yielded no definitive answers, but the current labor pool is certainly in the millions. (A recent survey claimed forty-five million American workers, about one in five, participate in gig work, yet this includes laborers supplementing full-time jobs.) The ramifications of people, whether by choice or necessity, working for multiple companies for shorter periods of time seems to befuddle American systems tweaked throughout the twentieth century with the idea of full employment and job security. Call it the new feudalism or whatever you want, Uber’s conception of employment is beginning of the new rule rather than some grand historical aberration. Pre-union America was built on wage labor based around contingent work that, by nature, would come and go. The original meaning of layoff was a “temporary release from employment” due to seasonal or project-based cycles. It’s only the technology that’s gotten better.

Zenefits, a software company which manages the administration of human resources and benefits, has created a platform that undercuts the labyrinth of paperwork and relationships traditionally associated with a hire. (And is now sort of collapsing because it undercut the system a little too hard, but.) A new employee logs preferences for health insurance, taxes and 401(k), registers their profile, and then, with the click of a “hire” button by a network administrator, gets connected to their benefits within an all-in-one dashboard. Current regulatory nightmares aside, it’s really a win for both employers and workers. Companies can easily hire and keep their employees’ benefits up to date, while labor can simply update their preferences without suffering through bureaucratic depression.

Zenefits also does for job termination what it does for hiring. Whereas a few years ago, a layoff meant severing an employee’s health insurance, 401(k) administration and payroll processing separately — an hour-draining series of paperwork, scanning, faxing and follow-up calls — access to benefits can now be cut by unchecking a box. Rather than investing in an employee, owners can add and drop based on what their company needs in real-time.

This ease of labor-swapping makes human resources feel like fantasy sports. If I’m running a company and the data tells me I need rebounds while you provide assists, I’m sending you back to the bench. Your previous stats, in the guise of healthcare and 401(k), remain associated with your account, and you’re welcome to carry those signed documents to your next job, as long as they use Zenefits, too. You’ll also still be able to access your vacation and time-off log, which the platform suggests can be used for “unemployment data purposes.” But really wouldn’t that time be infinite?

Zenefits won’t administer your exit interview, but I’d still be worried if I worked in traditional HR. Just as the Uber driver will be replaced by a robotic, “better” version of himself, so will human resources departments. Zenefits software classifies termination as either voluntary (quitter) or involuntary (fired), and can even mark you as regretted loss (they consider your layoff profound because you “had high potential” or were a “key contributor with a significant impact”) or non-regretted (you were not regarded, basically, at all).

“The willingness of workers to discard status privileges like desks and offices is not just a sign of giving in to executive demands for cost control,” writes Nikil Saval in Cubed: A Secret History Of The Workplace, his excellent history of the American office. “It also suggests that the career path that defined the white-collar worker for generations — from the cubicle to the corner office, or even from the steno pool to the walk down the aisle — is coming to a close, and that a new sort of work, as yet unformed, is taking its place.”

Job security will be left to decay in the supply closets of skyscrapers. The future office space is within a chat application; future departments are virtual rooms where work is transparently archived for future versions of you. This means job roles take on a more concrete meaning while the person doing the job is less important than ever. The best full-time employee is an efficient roleplayer; the worker, tied to her benefits, is free to float where she chooses, stitching together part-time jobs, connecting to health insurance where it’s offered, cutting back the red tape which makes working for someone new such an arduous process. The worker is tied to her past through employer performance ratings, which, along with certain digitized forms like the W9 and 1099, will follow from job to job. The “non-essential worker” tag or a bad driver rating could become our modern Scarlet Letters.

Work itself already shares the qualities an application. Like email or the office door before it, the worker opens their platform when they want to make money. Their profile seamlessly connects to other apps, the Slack channel which allows collaboration with other profiles, the Zenefits dashboard which ensures their health insurance is valid if they crash their Uber car. Layoffs are now the denial of access rather than a person’s severance from a traditional job. So it goes. Jobs have long been the stand-in which workers used as a shorthand for personal identity rather than what they really are: a thankless compromise necessary to participate in capitalism.