No Axe-Grinders Need Apply: The Legacy of George Plimpton

by Brendan O’Connor

Although no one currently on staff at The Paris Review ever worked directly with George Plimpton, the legacy of the editor of 50 years obviously looms large over the publication. Coincident with the 60th anniversary of the magazine is the release of the documentary Plimpton!: Starring George Plimpton As Himself. The cover of the Spring 2013 issue of The Paris Review was a photograph of a poster made by the French artist JR — Unframed: George Plimpton, 1967, from a photograph by Henry Grossman — designed to look like a cover (the Spring 2013 cover, in fact) of The Paris Review pasted on a wall in Paris.

There are as many layers in Plimpton! worth rolling one’s eyes at: George’s pedigree; his legacy; the mythology surrounding him to which a documentary would seemingly only contribute. Such eye-rolling would not be entirely misplaced: an unattributed newspaper headline displayed in the documentary reads, “Being Born To Lose Has Made George Plimpton A Winner,” although someone who can trace his ancestry back to the Mayflower, who can get kicked out of Exeter in his senior year and still end up at Harvard, who goes sailing with the Kennedy’s (and maybe dated Jacqueline Onassis?) hardly seems appropriately described as “born to lose.”

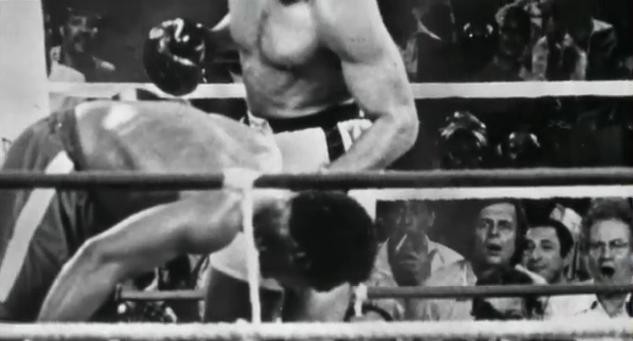

But looking past the man as brand, it becomes apparent that Plimpton retained through it all a sense of joy and wonder — mouth agape, Plimpton watches as Ali trounces Foreman — that deflates cynicism. Anyway it’s hard to think ill of a man who watched as Robert F. Kennedy, one of his best friends, was shot and killed by Sirhan Sirhan right in front of him. (Plimpton would help tackle Sirhan and disarm him. He never spoke of the incident publicly.) Later, during a period of economic turmoil, Plimpton appeared on a number of infomercials to help keep the magazine alive. If his writer friends looked down upon his practice of participatory journalism, one can only imagine the disdain they must have felt at such debasement.

There is something manifestly childlike in chasing and scattering a flock of birds. But then, those birds are buzzards, and the one doing it is George Plimpton, and he is somewhere in Africa because of course he is. Plimpton’s casual dictum on participatory journalism — “You become what you want to become” — is correct, though this is a world where the glaring qualifications go unspoken: “You become what you want to become, contingent upon the circumstances of your birth and access to the social, political, and financial capital that might enable such transformations.” (“I think I was one of the first middle-class people who’d ever worked at The Paris Review, and it concerned me that we didn’t have health insurance,” Mona Simpson once said.)

Plimpton! Starring George Plimpton As Himself

Plimpton! plays at the Film Society of Lincoln Center through June 6th. You can purchase tickets here.

The film is also rolling out to:

Asbury Park on May 31st.

Los Angeles on June 7th.

Palm Springs on June 14th.

Boston on June 21st.

It is the investigation of those circumstances and that access that is effaced in a magazine whose mission is simply to publish “the good writers and good poets, the non-drumbeaters and non-axe-grinders. So long as they’re good.” In place of drumbeaters and axe-grinders — critics and theorists and other such ideologues who write about fiction rather than actually writing it — The Paris Review gives further voice to the authors themselves. The authors, however, did not always see the value in such a proposition: in response to Plimpton’s request that he allow himself to be interviewed for the Art of Fiction series, Ernest Hemingway wrote, “I might say, ‘Fuck the Art of Fiction….’ But what I would really mean is, ‘Fuck talking about it.’ Let us practice it and shut up.”

Plimpton’s accomplishments as a writer and an editor are monumental. As with any monument, it is worth remembering how it was erected in the first place. In the documentary, someone — Peter Matthiessen? — says, “The point of The Paris Review was not only to publish creative work but to discuss it from the point of view of those who do creative work.” This avoids the question, “Who gets to do creative work?” The Paris Review’s internship program is unpaid, so some of the answer seems more or less clear. [Note: I am an unpaid intern.]

Ideologically, The Paris Review hasn’t changed much after Plimpton. Despite their recent involvement in down-home New York City issues — they joined in the effort to save St. Mark’s Bookshop from its own lease, for example — the publication still eschews criticism and theory and beyond. “Why would anyone care what we have to say about politics?” said Lorin Stein recently, in the magazine’s new Chelsea office. (The infamous office parties will never be the same, as you can discover in mid-June, when issue 205 is celebrated at their new home.)

Such a position is itself political. Distance from the politics of the day enforces those politics. “The Paris Review is apolitical in the narrow sense that we don’t, generally, publish polemics or report on the issues of the day, and we don’t judge writing by non-aesthetic standards,” Mr. Stein later wrote via email. “Any aesthetic has politics built in, if politics is what you’re looking for.”

There’s no avoiding the political meaning, Mr. Stein observes, of running an Art of Fiction interview with Ralph Ellison in 1955, or Erica Jong’s fiction in 1973. Or Dennis Cooper’s 2011 meditation on the rim job. “Clearly, we think it’s OK for grownups to talk to each other about rim jobs,” Mr. Stein wrote. “We also think such a discussion might have literary value. Does that aesthetic judgment have political implications? Maybe. If so, that’s fine by me.”

Sadie Stein, deputy editor of the magazine, only met George Plimpton once, at a party, but feels his influence on her work as editor of the Paris Review Daily, the magazine’s blog. There are things the magazine can publish that the Daily cannot, and vice versa, but what unifies it all, she said, is the emphasis on “one’s experience of culture.” The pieces that the Daily runs are usually about art, film, literature, music. “I like to think that in a small way a site like the Daily can provide pleasure and engagement without imposing a didactic agenda,” Stein wrote in an email. There are also a lot of posts about books.

Ms. Stein dismissed my protest that attempts to remain devoted almost solely to the aesthetic is either misguided or disingenuous. Such arguments seem “to presuppose that everything is intrinsically political, and I must say I find that somewhat reductive, and frankly a little frustrating,” she wrote. “All I can say is that we don’t aspire to be a news site and that we don’t have an agenda.”

The importance of Plimpton’s legacy in the digital era, for Stein, is in how he engaged with the world. “He liked people, he liked learning, and he liked to share what he learned,” she said. “That’s a guiding spirit that motivates the site far more than any political agenda.”

Lorin Stein quotes a letter from Plimpton to his parents in his editor’s note from the Spring 2013 issue: “What we are doing that’s new is presenting a literary quarterly in which the emphasis is more on fiction than on criticism, the bane of present quarterlies. Also we are brightening up the issue with artwork.”

Brendan O’Connor is an Awl summer reporter.