Zachary Woolfe: Another Long Vampire Weekend

by Zachary Woolfe

It’s easy to know that a band is good, and harder to know what they’ll mean for people. In 2006, I knew, as did a bunch of Columbia students and some folks on the Internet, that Vampire Weekend was good. I knew this only because I happened, at the time, to be dating a friend of two of the band’s members. In this capacity I would go to their shows, one of those relationship tasks that would have been pretty annoying if the band didn’t put on really good shows.

By the time their first album came out in January 2008, that boyfriend and I had long since broken up, and Vampire Weekend had begun to mean something to a whole lot more people-even to represent a minor moment. It feels like a long time ago, but things were good that year. New York City was in bloom and still working and building, and we, by which I mean its young people, felt in control.

We were set on taking the country back (remember how excited we were about that election?) and we were listening to Vampire Weekend, a crystal-clear sound, clean and clever and certain, that virtuosically combined every signifier of young New York life-”spilled kefir on your keffiyeh”-and captured how smart, how fun, how ironically sincere we knew we were.

They were a fine example of that classic New York dream, that this is actually a place where four kids-without real connections but with talent and hard work-can arrive and end up being rock stars. But theirs wasn’t the disruptive aesthetic of the beats or punks. It was instead an evocation of New York in the Internet era, a place where even the art values order and coherence and good sense. The songs pretended to be conflicted, the poses vulnerable-”The Kids Don’t Stand a Chance” even seemed, as explicitly as Vampire Weekend lyrics get, to criticize the investment banks and consulting firms that had seduced their, our, friends. But the ease and capaciousness of the lyrics’ references, the casualness of the music’s appropriations, made clear that this was music about feeling good about feeling powerful.

And powerful was what we wanted to feel. Vampire Weekend had the the sound of confidence-the confidence that, with Wikipedia open on our browsers, we could talk about Lil Jon and Chinese commodity deals one after the other, and with equal authority. “As a young girl/ Louis Vuitton/ With your mother/ On a sandy lawn”: their lyrics were like a Nancy Meyers movie made just for us, permitting us simultaneously to have and to feel superior to a fantasy of wealth and coolness. Vampire Weekend meant something to us because, seemingly effortlessly rich and knowing, they meant everything that we’d been promised about New York, about the future. There’s a novel in which one character says to another, “How nicely you talk; I love to hear you. You understand every thing.” That was Vampire Weekend. They understood every thing.

Of course, since January, 2008, a lot has changed. The assumptions we had about the future and about New York, the contracts we thought existed, now seem silly. Things aren’t secure; jobs aren’t there; where we wanted certainty, we got compromise; there’s been a halt in the building of all those Brooklyn condos leading the gentrification that the band both parodied and epitomized.

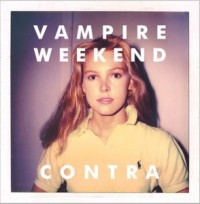

Into this new environment-another January, two years later-arrives Contra, the band’s second album. “Here comes a feeling you thought you’d forgotten,” goes the catchphrase of the opening track. Everything has changed, but Vampire Weekend remains stubbornly the same, still singing about college girls in intricate, quasi-inscrutable lyrics set to hand-clappy syncopated beats. There’s still the same virtuosity; they’re the same, but bigger-expansive where the first album was intimate-and even, on “Giving Up the Gun,” a little light-techno-ish.

It’s as if the band is determined to exaggerate everything, right or wrong, that’s been said about it. Their first album drew endless comparisons to Paul Simon, whose lyrics were also enigmatic and whose sound at times also drew on “world music.” These comparisons rang a bit false last time, but the new album really does often sound similar to Graceland; the ecstatic horns on “Run” descend directly from “You Can Call Me Al.” If that’s not 80s enough for you, they’ve also thrown in a lot of synth beats for good measure. (Is that “Walk Like An Egyptian” casting its shadow over “California English”?) And those infamous Afropop riffs, which give the band its fundamental sonic character but got it widely tagged as semi-racist, are if anything more omnipresent than on the first album.

But an exaggerated, inflated sameness feels irrelevant when so much has changed. The cleverness that was so dazzling on the first album is now a little tiresome, as in the lines from “California English” that give Contra its name: “Contra Costa, Contra Mundum, contradict what I say/ Living like the French Connection, but we’ll die in L.A.” (One of the conceits of the album is that it was inspired by, and largely recorded in, California.) And while the murmurs of racism surrounding the first album were always ridiculous, a second helping of similar beats is wearying.

Their big, shiny new album stands there like one of those big, shiny, half-built condo buildings in Williamsburg, full of empty fridges waiting to be filled with the Aranciata sodas and kefir yogurt drinks that populate the lyrics. Both the album and the buildings look strange after the disappointed certainties of the past couple of years, the frustrated promises. It’s an context in which the beautiful parts of the album are almost bizarrely moving. The rushing horns of “Run”; the precise, melancholy strangeness of “Taxi Cab”; the first time the backup vocals come in in “Horchata” (but not any of the times after that): Vampire Weekend is still capable of understanding every thing, but that’s not as reassuring as it was.

It is entirely possible, and even likely, that my date to the high school prom was the inspiration for some of the songs on Vampire Weekend’s debut album. After all, that’s the deal, right? You date a songwriter, the love songs are about you? In any case, the timing checks out. I only tell you this because this girl-my prom date-happened to be, for a few years, a source of overwhelming, almost scary certainty and authority in my life. There were years after we stopped talking that I missed her, but wasn’t that some time ago now.

Zachary Woolfe writes about culture right here and for the New York Observer.