Who Made The First Rice Krispies Treat?

Searching for Mildred Day

My mom never made Rice Krispies treats. She didn’t have to. It seemed like everyone else’s mother always had a batch at the ready, for birthday parties, after-school snacks, bake sales, picnics and potlucks. It was an abundance of sameness. A collected Stepford-like mind-set of puffed rice cereal, marshmallows, and butter. On occasion, there would be an exciting break in the monotony — the rare “eccentric” neighbor swapping Rice Krispies with Froot Loops, creating a multi-colored, shimmery specimen influenced by Timothy Leary. But mostly, I was bored by them (I was a very affected teen and pretended to be bored by almost everything). I took them for granted. If they were around and I was hungry, I would eat them. If they weren’t, I never thought about them.

Much later, I came back to Rice Krispies Treats, obsessively, during a period of mild self-loathing. I had just finished writing my third cookbook, Baked Elements, and I was feeling unpleasantly doughy. My gut, never exactly flat, was giddily exploring foreign territory and my skin felt uncomfortably tight. Writing a cookbook is great fun, but testing each and every recipe (some many multiples of times) can be maddening. Dessert cookbooks are doubly masochistic. It’s an unholy cycle of cake and cookies and brownies — a constant sugar high feedback loop without a lean protein or leafy green in sight.

I had been through this transformation before with my prior cookbooks, but this time was worse. I was older and less elastic. It was in this pudgy, shaky, sweaty state (instantaneous and uncontrollable sweats were another ailment I developed from consistent cookbook testing) that I ambled into a Starbucks in February 2012, and ordered their version of a Rice Krispies treat, the Marshmallow Dream Bar. I ordered it not because I was a fan, but because according to the hybrid price/nutrition card, it had less than half the calories of everything else in the pastry case. This was my form of dieting—the Dream Bar, at a mere 230 calories, was my way back to salvation.

The basic recipe for Rice Krispies treats uses only three relatively inexpensive ingredients and can be put together in about 5 minutes or less. This simplicity guaranteed its ubiquity. It is a nearly foolproof recipe with two important attributes: 1) it does not require an oven and 2) its main ingredient, puffed rice, is often completely uniform due to the brand dominance of Kellogg. Ovens are temperamental beasts at best, and sudden spikes in temperature and undiscovered “hot spots” can ruin (at least for an evening) even the most accomplished home cook. Chocolate cake can vary greatly based upon the brand of chocolate (cacao, sugar, and milk solids are vastly different from brand to brand), type of cocoa powder used (Dutch-process vs. natural), and even the amount of protein in the regional flour. But Rice Krispies treats are dependable. It is the kind of recipe that suggests a crude (or maybe shrewd) entrepreneurial skill, and bit of (subconscious) wit. Three weeks into my makeshift post-cookbook detox, I set aside a day’s worth of work to uncover the magician behind the recipe.

The origin of a recipe is often as important as the recipe itself. A recipe that is steeped in fable — a fantastic narrative seeded with bits of truth — is much more appealing to a broader public. Though not universal, most of these creation myths have a few things in common. First, the recipe inventor must be relatable — the more normal the better. Secondly, and most importantly, the creations are more viral if they are accidental. For some reason, we — and especially the media — love accidents. We love non-accidents as well (hello, Cronut), but fortunate mishaps appeal to a primal human condition: hope. And, if not hope, it’s hard not to be amused by dumb luck. After all, Ruth Wakefield accidentally created America’s most famous cookie. Or did she?

Ruth Graves Wakefield created what we have come to know as the chocolate chip cookie. The original version, the Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookie (named after the restaurant she owned in Whitman, Massachusetts) became a sensation. Today, there is nary a soul unfamiliar with her handiwork. But the story of how Ruth created the cookie is a bit more nebulous. The official Nestlé version (per the corporate website):

One day, while preparing a batch of Butter Drop Do cookies, a favorite recipe dating back to Colonial days, Ruth cut a bar of our NESTLÉ® Semi-Sweet Chocolate into tiny bits and added them to her dough, expecting them to melt. Instead, the chocolate held its shape and softened to a delicately creamy texture.

The more probable version is more nuanced and is told from many perspectives in Carol Wyman’s wonderfully detailed and researched book, The Great American Chocolate Chip Cookie Book. Carol’s quote from Phyllis Hanes of the Christian Science Monitor sums things up nicely:

It was one year after a trip to Europe that [Ruth] remembered some chocolate experiments she…made in a college food-chemistry class. She ordered some chocolate bars from the grocery [and] after testing and experimenting, she and her pastry cook, Sue Brides, came up with a new cookie.

I was rankled by the Nestlé version of the story. I felt it demeaned Ruth’s legacy and belittled her intelligence. At face value, the Nestlé history implies — in an unflattering, retro kind of way — that Ruth’s creation was not the byproduct of careful work and research but rather a happy accident. Was there a whiff of sexism in their retelling? If Ruth were a man, would the origin story be less whimsical?

Nestlé spokesperson Roz O’Hearn was eager to report that Ruth (whom she never met, but knows much about) was a “shrewd businesswoman,” a “food scientist,” and very smart. This seems to square with Carol Wyman’s reporting as well, wherein Ruth comes across as exacting and sharp (to put it mildly). You get the sense that accidents were not tolerated in Ruth’s kitchen. When I asked O’Hearn about the discrepancy — the difference in origin stories, she said, “In the end, it doesn’t matter, they are both great stories about a great cookie.”

So what about Mildred Day, the woman attributed with inventing the Rice Krispies Treat? Unlike Wakefield, a lone entrepreneur, Day was employed by Kellogg when the Rice Krispies treat was first developed. To date, the best article I could find about Day was from The Des Moines Register in an article by Tom Longden. The profile, from a series on famous Iowans, details her life, including her time at Kellogg and beyond. In addition to creating the Rice Krispies treat, the author suggests (by way of Day’s daughter, Sandra Rippie) that Day also served the “very first airline meal…to a group of magazine food editors.”

But did Day actually design the Rice Krispies treat? I called Rippie, who told me she has fond memories of her mother, but not of Rice Krispies treats. Her mother had told her she never wanted to make them again because she used to make them endlessly. This is understandable—Ruth Wakefield was supposedly entirely fed up with hearing about her cookies and spent an eternity trying to shift attention away from them to her newer creations.

At Kellogg, it was hard to find a real live person to speak with. Eventually, through a series of emails with a helpful company spokesperson, I was able to piece together the history of Mildred and the Rice Krispies Treat. Initially, I just wanted confirmation that Mildred created the treat. They responded:

Our records indicated that Rice Krispies Treats were invented in 1939 by the Kellogg Home Economics Department. Our records also show that Mildred Day worked in the department from Sept. 28, 1928 to May 1933 and Oct. 7, 1935 to Nov. 1936. We cannot attest to any role she may have played in Rice Krispies Treats development.

Assuming Kellogg is correct, it would stand to reason that Day was not even employed at the company during the birth of the treat. But buried within the Tom Longden article is a strange piece of information — a piece of information that suggests Mildred was part of the recipe invention. In the article Tom references a trip Mildred made to a Camp Fire girls (like Girl Scouts but sans badges) event. From the Tom Longden article (which I quickly forwarded to Kellogg):

Rippie says that about six months after the invention, Kellogg’s received an inquiry from a Camp Fire girls organization in the Kansas City area, pleading for ideas for a fundraiser. Kellogg’s decided to test-try what it initially called “marshmallow squares,” and put Day on a train for Kansas City. She took with her huge, specially made baking trays and a giant mixer.

Kellogg’s response:

After further research, we can confirm that in 1932, Mildred Day attended a Campfire Banquet and had 1,600 Rice Krispie Bars.

What? First, this would contradict the earlier email. If Mildred had 1,600 Rice Krispies Bars in 1932, then the bars must have been invented before 1939. And second, Kellogg had some serious record-keeping going on if they knew the number of treats delivered in 1932. I went back to Kellogg (again, via email) and asked them to help with the discrepancy. The quick response:

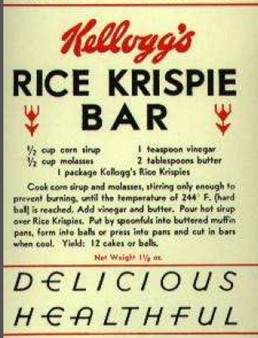

The recipe for the 1932 version (below) is different from 1939.

This makes sense. Sort of. It would seem that Mildred Day did have something to do with the first Rice Krispie Treat, though if you review the 1932 recipe (and I will rightly or wrongly refer to this as Mildred’s recipe), you will notice that it is made without marshmallows. Which is hard to imagine, and even harder to eat. Nonetheless, it is a Rice Krispies Treat.

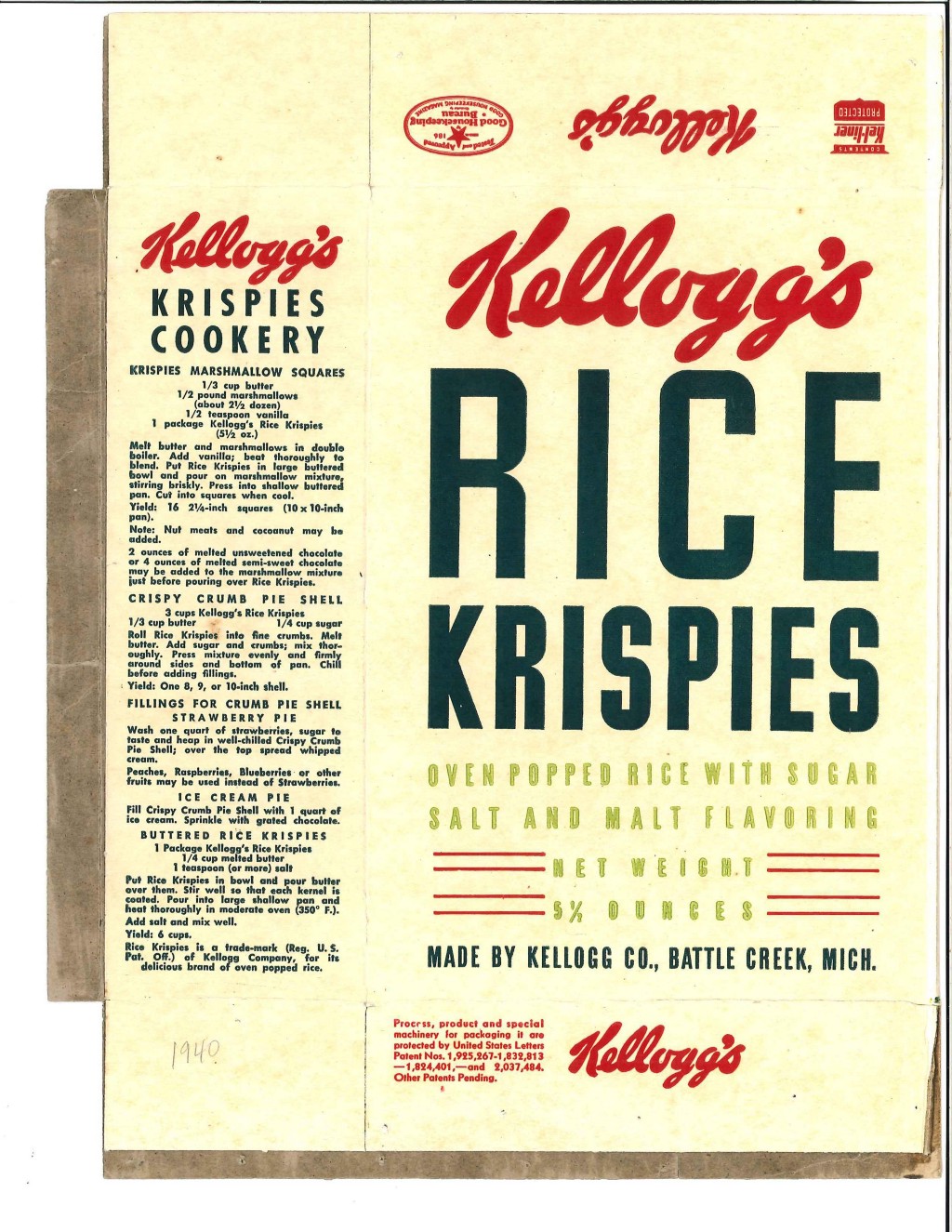

This below image shows (according to Kellogg) the first recipe (with marshmallows) printed on a package in 1940:

Kellogg has every right to their timeline, but it does seem odd not to at least acknowledge the earlier version of the treat in the company history. The probable cause (and this is pure deduction on my part) is that a large corporation, fearful of hungry lawyers, is probably slow to dole out individual recognition of a treat that has helped sell many billions of dollars’ worth of cereal.

Regardless, I needed something explicit from Kellogg. I needed closure. Something that would tidy up all the various bits of information tying Mildred to the Rice Krispies Treat. A simple, pleasurable denouement. I sent my last desperate (prodding, pushing) email to my virtual Kellogg girlfriend:

To confirm, the 1932 treats (the ones without marshmallows) were still called Rice Krispies Treats? However, Kellogg’s is recognizing the 1939 version (the one with the marshmallow) as the year the treats were invented? Correct?

And finally, is there anyway to confirm that Mildred Day had anything to do with the 1932 version?

The delayed response arrived. It was graywashed corporate-speak, but there were glimmers of a more complicated origin story in the layers of carefully chosen language. I knew it was all I would get. I took it.

The 1932 recipe was called Rice Krispie Bars (without the marshmallows). Mildred was employed between 1928–1933 and 1935–1936 so she was part of the staff when the recipe was developed.

Kellogg Company recognizes 1939 as when the now known as Rice Krispies Treats were invented.

Finally, it should be noted that Malitta Jensen is often mentioned in several articles as the co-creator of the Rice Krispies Treat. I could not find anyone to corroborate this information, though it would stand to reason that Jensen had something to do with the 1932 version (the marshmallow-less one) and she deserves equal recognition. As with all creation myths, the web is rife with misinformation and interpretation about Rice Krispies treats — timelines and appropriation shift from article to article. For the purposes of this article, I solely used Kellogg’s research/media department and Mildred’s daughter, Sandra Rippie, to put the puzzle together.

Mildred would be happy, I think. The Rice Krispies treat is having a revival of sorts. It is on trend. It was (mostly) gluten-free before gluten-free was a thing. And it is relatively low in fat and calories. Pinterest is rife with riffs on the treat. Industrious and famous cookbook authors are reinventing it for a new generation. Deb Perelman, of Smitten Kitchen fame, included a recipe for Salted Brown Butter Crispy Treats, in her best-selling cookbook, The Smitten Kitchen Coobkook and Amanda Hesser included a Caramelized Brown Butter Rice Krispies Treats recipe in The Essential New York Times Cookbook.

I like to think I am doing a little bit more to raise Mildred’s Q-score. In the newish Baked cookbook, Baked Occasions, I (along with co-author Renato Poliafito) pay homage to Mildred with a completely goofy (but fun) recipe—a Chocolate Rice Crispy “Cake” with Homemade Marshmallow “Icing,” to be consumed and celebrated on Mildred’s birthday.

Matt Lewis is a founder of BAKED and an occasional cookbook author. He hates cilantro and loves chocolate cake.