Time of Your Life

by Nicole Boyce

I saw the first denim scrunchie before I’d even reached the venue. A woman in front of me was wearing a Sandlot t-shirt with the caption, “You’re killing me, Smalls!” Another woman, wearing a shirt that just said, “The 90s,” posed a friend for the camera. “You’ve got to move the vest so we can see the t-shirt,” she said. “There ya go.” Her friend’s t-shirt read, “You’re a virgin who can’t drive.”

I’d been thinking recently about the way that nostalgia is now being sold back to millennials — the past marketed and re-experienced for a fee — which is why I was waiting in line on an overcast Saturday morning in Brooklyn for the inaugural 90sFest, a one-day music festival featuring Coolio, Smash Mouth, and Salt-N-Pepa, among others. Organized by promoters Leuven Media, Prime Social Group, and Founders Entertainment, tickets for the festival sold for between $50 and $150. (It was far from the only marketed experience capitalizing on millennial nostalgia this year: Marketing Magazine, Adweek,and Forbes have all run articles on nostalgia marketing in recent months, while Vogue called 2015 “the summer of 90s music”; Marilyn Manson did a summer tour with Billy Corgan; and Sugar Ray recently finished a tour with Eve 6, Better Than Ezra, and Uncle Kracker.) As we approached the festival gates, I peeked inside at the scattering of side ponytails, chokers, and butterfly clips. It was like the blue fairy had waved her wand over a BuzzFeed gallery.

I’d been inside for less than five seconds when someone handed me a promotional bill printed with a Mars Attacks alien, Kevin McCallister, and the logo for SmileTrain, 90sFest’s charity partner. I spotted a cluster of Rugrats mascots and hustled over to get a photo, but couldn’t figure out where on the mascot’s foamy body to put my hand. Did I just accidentally touch its butt? Which part is the butt? The mascots were standing between a Sunny D booth and something called Betches Bedroom, a detailed re-creation of teenage girlhood stocked with Beanie Babies, an *N Sync poster, and Steve Madden memorabilia. A woman in a tattoo choker manned a GIF photobooth inside. “Where can I get one of these?” a visitor asked her, holding up a pillow that said “#Betches Love the 90s.”

“Sorry, we made those special,” the choker-wearing staffer said. Her co-worker joked to me, “Maybe we should sell them.”

“Bet you could make a fortune,” I said.

She laughed, then looked at me earnestly. “We are selling tank tops, though. They’re $44.” She pointed at a grey tank top printed with the words, “Dawson’s Fleek.”

When it comes to re-experiencing our youth, we can’t divorce memory from economics. The Atlantic’s Megan Garber has described the current state of nostalgia as a “memorial-industrial complex. While the word “nostalgia” used to be associated with Madeleine-induced warm and fuzzies, Garber explained, now memory is often experienced as a media product. Our past — thanks to the Internet — is instantly accessible and always available for purchase. As Trent Moore declared in his recent Blastr critique of Hollywood’s Jurassic reflux: “For better or worse, nostalgia is the new currency.” 90sFest, then, isn’t just whimsical marketing: It’s calculated economics. As Bruce Starr of BMF Media Group noted in an interview with BizBash, booking nostalgic acts is extremely cost-effective, since the hit-makers of yesteryear typically bill less than artists with current no. 1 singles, all while tapping into built-in fan-bases and publicity potential. For attendees, throwback festivals are a chance to reminiscence, and an excuse to revisit acid-washed jeans. The experience isn’t just about the music, but about the overalls andfloral dresses that are enjoying their comeback heyday. Blogger Vladimir Vukicevic has theorized an S curve for nostalgic appreciation that’s visible in the fashion industry: Pop cultural items move from an establishing event and gradual appreciation period to a nostalgic apex — usually twenty years after the fact — then depreciate as nostalgic capital. If fashion is a Venn diagram, nostalgia is the spot where hipster and Hanson overlap, and 90sFest is a hyper-concentrated version of that performative nod backwards.

“My name is Pauly Shore,” our host announced as he took the stage shortly after 2pm. He looked tired but self-amused in a loud printed t-shirt and shorts set, his Son in Law hair long since cropped off. He began hyping up the crowd, gesticulating with a bottle of Sunny D. “How many Lisa Loeb fans are here?” he asked. A big cheer. “What Lisa Loeb songs can you name?” The crowd went quiet. “You don’t like Lisa Loeb,” he sneered, then started listing his movies — Biodome, Jury Duty, and Encino Man — which elicited another huge cheer. “Those are all movies from the nineties,” he said, squinting out into the crowd. “They asked me to host because that’s when I was really popular.” The crowd laughed, then got quiet again, unsure of whether we were supposed to laugh. “At least I’m still fucking alive, right?”

“Everybody (Backstreet’s Back)” played on the speakers and Pauly gyrated in his Hawaiian outfit, shouting at people to dance. “You guys, this was life before the fucking internet!” After what felt like many minutes, he left the stage and the band Tonic stepped on, launching straight into “Open Up Your Eyes,” a crowd-pleaser. I was struck by how many Tonic songs I know — “You Wanted More,” “Sugar” — and by how tight the band’s performance was, delivering well-harmonized vocals and spot-on instrumentals. If Tonic is washed up, they’ve washed up wholly intact. It occurred to me then that 90sFest was not just a fashion show or an orgy of elastic cuffs and orange drink: Tonic is a seasoned band who plays well-loved numbers, and for them, 90sFest wasn’t a novelty act, it was a music festival. After indulging us with a group sing-along to “If You Could Only See,” the band left the stage and the festival’s kitsch flowed back in full force. A man dressed like The Mask strutted past the Sunny D booth, a woman wore a Spice Girls collectable sticker on her bicep, and another woman, in pastel cargo pants, flirted with a man in a vintage t-shirt. I hadn’t seen anyone flirt in cargo pants in a long time.

Over the course of the day, I talked to a number of festivalgoers. Katie, twenty-eight, wore overalls and a backwards baseball cap, while Ashley, thirty, had a row of butterfly clips in her hair. They both live in New York, and found out about the festival through a Facebook ad.

“Is there a band you’re especially excited to see?” I asked.

They shook their heads. “None of the performers are my favorite nineties performers,” said Katie. “But I know a handful of songs from each, so I thought, ‘It’ll be awesome.’”

I knew what she meant. I too have fond, if vague, recollections of most of the performers, but I don’t own an album by any of them. I asked about the outfits. Ashley bought her butterfly clips from a stand in the festival’s marketplace, while Katie’s overalls came from an H & M. She mentioned something that came up with every person I talked to — how difficult it was to tell en route who was dressed up in nineties garb for the festival and who was just from Brooklyn.

I asked Katie about her shoes — Vans with hearts doodled on the side — “That’s how you can tell they’re from ten years ago,” she said. “I haven’t drawn on my shoes in ten years.”

Next, I talked to Olivia, twenty-five, and Sanders, twenty-four. Olivia said the outfits were the biggest reason she wanted to attend the festival. “I actually bought this whole thing,” she said, pointing at her backwards hat, overalls, and leggings. “I went to both Goodwill and Spencer’s yesterday, I’m ashamed to admit.” She did a lot of internet research to curate the look. “This is mostly based on Clarissa Explains It All.”

“Where did you get your fanny pack?” I asked Sanders.

“Some friends gave it to me in college,” he said. “It’s actually a JammyPack.”

That sounded to me like a cartoon onesie gang, but Sanders demonstrated that the pack housed a mobile speaker system. This was 2009 dressed up like 1993, resurrected in 2015. Nineties culture, over time, has been essentialized into a few symbols: phat pants, Doc Martens, mini buns.

Around 3:30pm, Coolio took the stage in a hat customized for his braided pigtails. Midway through his performance, a recording of gunshots played, and Coolio left the stage. He returned, wearing neon orange Wayfarers and a Notorious B.I.G. t-shirt, then launched into “Gangsta’s Paradise.” Ecstatic howls rang out through the crowd. Hundreds of people in vintage plaid started waving their hands in unison.

The venue — a large fenced lot — was packed by then, and I wondered whether 90sFest was delivering on its Pog-centric advertising. “I think it’s pretty good for [the festival’s] first year — good turnout, good food,” Olivia had said. Her one critique? “I wish Shaggy was here.” Could 90sFest just be a pretty good way to spend a Saturday afternoon? There’s something to be said for a guy in a Where’s Waldo costume playing giant Jenga with his friends and having what looks like a kickass time. Those of us at the festival weren’t unaware that we’d paid $60 for the tickets and too much for Bud Light; we were being marketed to, but not necessarily duped. And for the first time, I felt real nostalgia: not for Rugrats or Steve Madden shoes, but for a time when I was less skeptical about buying the experiences I love.

Around 4:30, I weaved back through the crowd to watch Lisa Loeb perform under increasingly ominous clouds. After Perez Hilton introduced her — and talked up his role in the upcoming Full House musical — Loeb launched into her new material. The crowd chattered as if she wasn’t onstage. Admittedly, I didn’t find the new material gripping either, but I still cringed when I heard a woman behind me say what we were all thinking: “I don’t want to hear the new album stuff. I want to hear the old stuff.” As Loeb continued playing, a man beside me said, “Wow — look at her arms!”, presumably referring to Loeb’s toned biceps. A guy further back in the crowd shouted out: “I made my girlfriend buy your glasses!” How many of us have made sexual choices based on nineties pop icons?

When Loeb played the first chord of “Stay,” everyone paid attention. We all knew the words, and we all sang along. It was a beautiful moment in a bizarre context — the direct evidence of the song’s emotional impact, concentrated over time. And it struck me how unusual it is to hear the favorites of my childhood performed live; I was too young to go to concerts then, and my taste has changed now, so the songs hang, disembodied. Introducing “Stay,” Loeb said, “This song has taken me all over the world, so I always love to sing it.” The guy beside me smiled patronizingly. “Good for you, Lisa Loeb. Good for you,” he said.

The essentials of herd musicality are unchanged from my teenage experiences at Warped Tour — the back pain, the fickle weather, the smell of weed. Time, however, has brought us cellphones to hold aloft and earplugs to embrace. Most importantly, we could drink in this time-warped nineties, which lent the festival a messy undertone. By 5pm, a line had formed for the beer tent. The foam Rugrats got up on stage with some Spice Girls impersonators to do the Macarena, and people all around me started half-assedly flopping through the movements, Budweisers in one hand.

I found Joey, forty-one, watching the crowd warily. I asked whether the festival was living up to his expectations. “It’s kind of a big disappointment,” he said. “I feel like I’m in jail in the nineties,” he added, referring to the lack of in-and-out privileges. He preferred a recent Sugar Ray and Everclear concert that “was more like a regular concert. Less commercial.” In fact, his biggest beef with 90sFest was that “Nickelodeon is overrepresented and the U.K. as a whole is underrepresented.”

Joey was right that Nickelodeon was everywhere. It had been “sliming people” throughout the afternoon at a booth branded with the words “The Splat,” which was later announced as the name of its new all-nineties-all-the-time network. In the crowd, the “ewws” of childhood had been replaced with the calm remove of adults watching something ridiculous. “That looks water-based,” a guy behind me noted as one woman was splatted. His friend nodded. “Yeah, water-based.”

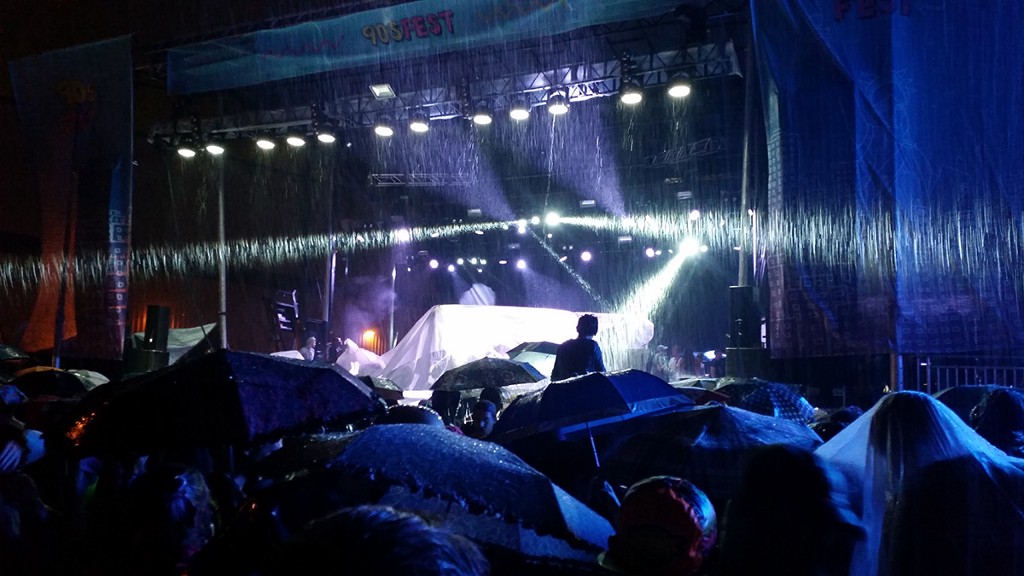

As dinner time approached, Pauly Shore bounced onstage again and delivered hype lines peppered with variations of “motherfuckin’.” The DJ — Suga Ray — played songs poached from Carson Daly-era TRL. Then Blind Melon took the stage and delivered a decent performance, with Travis Warren, the non-holographic replacement for deceased vocalist Shannon Hoon, singing “No Rain” to a crowd of people wishing for umbrellas. At 7:30, Pauly Shore got the Nickelodeon slime treatment, and left the podium looking a little annoyed. I sympathized, damp from the rain, re-living my worst nightmare of the nineties — standing in front of my male peers with limp bangs.

Darkness fell as we waited for Smash Mouth. A man beside me was using a Treasure Troll as a pocket square. People sang “a-yo, a-yo, a-yo, a-yo,” and I wondered how “No Diggity” has never been appropriated as a mayo jingle. I was surprised at my relief to see Pauly Shore take the stage in a new, even more brightly patterned suit. “Are you ready to smash your mouth or what?” he shouted.

Perhaps because of the rain delay, Smash Mouth wasted no time and launched straight into the favorites: “Can’t Get Enough of You Baby,” “I’m a Believer,” “Walkin’ on the Sun.” No one threw bread at them, so they didn’t swear at us. It was a serviceable performance but I couldn’t shake my longtime distaste for the band; I tried to picture them playing a small venue in the early nineties, people in the crowd saying “Damn! They’re gonna be big!” All around me, people were singing “All Star,” riding on each other’s shoulders. The band departed with a triumphant bow, then Pauly returned, shouting, “Yeah! That was sick!” The ground was paved with empty beer cans and crushed sunglasses. “Let’s give it up for god tonight, bringing us this beautiful moment. Praise god, praise the lord,” Pauly said. Then, shortly afterwards, “Play Weezer for the motherfuckin’ Weasel!”

By 9, I’d nearly had my fill of the nineties. I’d encountered a soggy fanny pack in the port-a-potties, and watched a drunk couple slow dance to Chumbawamba. But it was time for the festival’s headliners, Salt-N-Pepa, who exist in my memory as three songs: “Whatta Man,” “Let’s Talk About Sex,” and “Shoop.” They burst onto stage singing none of the above, but I couldn’t take my eyes off them: They had sparkly hats and male back-up dancers, coordinated dance moves for every song, and slick vocals. “I just wanna say, Salt-N-Pepa are coming up on our thirtieth anniversary,” Salt said. “And still got those sexy Tina Turner legs.” Then she told us, “This is not a show. This is a Salt-N-Pepa experience.”

That experience took us to “Let’s Talk About Sex,” with the back-up dancers spanking Pepa’s leather skirt. Then “Jump Around,” “Sweet Child of Mine,” and “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun,” during which Salt invited women up on stage to dance with her. She extended another offer during “Whatta Man,” calling up “all those good men out there.” Pauly Shore shimmied back onstage. Finally, they delivered high kicks during “Shoop,” their backup dancers bringing out the iconic leather jackets, white and yellow with red letters. Afterward, they got slimed — albeit, in plastic ponchos — and left the stage dripping green sludge. Whether by rain or slime, everything left 90sFest dampened.

Through the detritus of an exploded decade, I worked my way to the door. The Betches Bedroom had closed for the night; a man ran past to steal its Clueless poster. Walking toward the subway, I saw another man with the “#Betches Love the 90s” pillow tucked under his arm. We had literally looted the past. In some ways, I was glad we did. There was an element of camaraderie to 90sFest — people were reminiscing with friends, complimenting strangers’ outfits, exchanging knowing glances during Billboard hits. There were also times when the experience felt cheap, despite its expense — the blatant sponsor-plugs made me feel like we’d paid to take part in a giant Nickelodeon commercial.

Three days after the festival, 90sFest tweeted about “the next #90sFest.” The past is a resource that keeps on giving. I wonder though, will we still buy tickets after two years, five years, ten? Can our nostalgia sustain this festival indefinitely? If it can, I’m going to need more slap bracelets. And if it can’t, don’t worry: I’m sure someone’s working on #AughtsFest.