Foreign Bodies

by Muna Mire

I was eleven years old when 9/11 completely changed my conception of both the world around me and my place in it as a child of Muslim parents. It began slowly and then escalated: First, my parents quietly instructed us not to volunteer that we were Muslim in public. Then, a peer announced to me that he hated Muslims before the entire class. And, eventually, after being “outed” as Muslim, I began to go by my grandmother’s nickname for me, “Mimi” — something I had never considered doing before. I did that for the rest of my time in school, up until university. I erased myself, something which wasn’t hard to do as a Black Muslim.

It feels like we’re in an eerily similar moment now — one in which Muslim bodies, undocumented bodies, Black bodies, all ostensibly foreign bodies, really — are generating a lot of public anxiety, which is now structuring political discourse more forcefully than at any other moment in the last fifteen years. I wanted to find a way to interrupt what feels like history repeating itself by gathering some of the most insightful Black, Brown and Muslim people I knew to have a roundtable discussion on our mutual experiences in the post-9/11 age. Alok Vaid-Menon is a South Asian performance artist and one half of Darkmatter; Fariha Roisin is a writer and one half of Two Brown Girls; Amani Bin Shikhan is a writer and host of the whatsgood? podcast; and Asam Ahmad is a writer and the creator of the It Gets Fatter project.

What does the term “surveillance culture” mean to you? My first thought is of the state, but that’s not the only context. I think of policing, both of public space and private communications — directed with violence at Black, Brown, and Muslim bodies, particularly post-9/11. It’s important to look at the intersection of the former with the policing of poor, sex working, and gender non conforming bodies: What is and isn’t sanctioned? Who is and is not deviant? What form does this policing take? How does it impact people’s individual thought processes and behaviors? How have you personally experienced these surveillance structures? How did you navigate them?

Alok Vaid Menon: Surveillance culture isn’t just a specific set of state policies, isn’t just a moment or a trend — it’s a logic of colonialism and imperialism whereby all parts of ourselves must be rendered visible and therefore identifiable, categorizable, and ultimately containable. The only way that we come to understand and define ourselves is through a routinized and normalized ritual of public confession, articulation, and the production of public discourse, whether it be a series of identities that we attach to our bodies to become more coherent or an outfit that we wear to communicate who we are. The parts of us that we hold back from the mandate of visibility (and therefore the mandate of regulation) become seen as suspicious; the unfamiliar becomes the stranger, the unfamiliar becomes the terrorist.

Fariha Roisin: I think of all the times that I white-washed myself through the act of disowning my browness. This bodily performance is what I find a lot of people of color inhabit, and adopt, to feel safe. All the times I understood, inherently, that whiteness was better than whatever I was, I foiled myself in an outer layer of it to protect myself from abuse of the outside world. I felt like I had scales; I felt like I was completely unworthy of anything good. I absolutely disgusted myself on every level.

So, it’s sort of impossible that, now, I think I’m beautiful — but it’s taken me my whole life to get here. Like when I take a selfie, and I know I look good — I’m terrified of putting it out there, because what if I don’t? I think because I’ve always been a very intuitive person, especially as a kid, I was like a medium, so I would pick up on other people’s energetic mistreatment of me and introject it into my body as a form of remembrance, like a badge, and anytime I’d begin to feel good I’d tap into those feelings and remind myself: You’ll never be enough, Fariha. You’re not white.

I think I felt this way, also, because I didn’t have a lot of people of color as friends growing up. I mean Australia (where I grew up) is a wasteland of whiteness, and racism, so I didn’t really have a sense of togetherness that I feel exists in North America on at least some kind of level. I changed my name growing up so many times, preferring standard white names to deflect my strangeness. I hated people mispronouncing my name, and then joking about it, like,“haha Ferrari.”The way that I navigated so uncomfortably through my skin, always feeling outside of who I was, feeling in so many ways that my body didn’t represent the person I felt myself to be, as in a cool, quirky white person. Then, when 9/11 happened, I wasn’t even sure how to be a person, how to walk around in my super white school where I was already a weirdo because I didn’t read/watch/listen to what my peers listened to. I’ve always felt like such an alien, as I was always different in so many ways possible, so how could I even begin to learn and like myself? Being Muslim in a post-9/11 world, and actively identifying with that identity (even if it was a secret for so many years from my peers through my misplaced sense of self protection) has so much shame tethered to it. It was just another distinguishing aspect of how I was so wrong.

When people of color talk about their experiences of fear and ridicule, when they talk about their bodies — and trauma linked to those bodies, it’s so subversive. I think there’s nothing more powerful than to tell someone — someone who has actively resisted all that they are — that they are beautiful, or that they are seen, that they are valid in their identity. That they don’t need to be different to be powerful, to be smart, to be engaging, to be beautiful. That they are enough.

Policing is silencing. Policing is dismissing. Policing is denying. Policing is judgement. Policing is assuming. These are all the ways in which we’ve all been, and continue to be, policed.

Amani Bin Shikhan: The word surveillance instantly makes me think of Sydette Harry’s piece on the ways in which Black women are surveilled in every sense of the word, especially in the age of technological ‘freedom’ and shift of capital. As a woman who is equal parts Black, Muslim and immigrant, surveillance is not a new concept to my personal life or the lives of people who share any, or all of those experiences. I feel surveilled in the obvious, normalized gaze of the state by way of increased police presence in the most ordinary of spaces and in the incessant over-the-shoulder glances as I or my brother or my friend browse the halls of a given establishment; in the many instances where former professors and teachers have dropped my grade for choosing a topic too controversial, too strongly worded, too opinion-driven; and in the years that I burned my curls until they no longer bounced, only to wrap them as tightly as I could under my mother’s hand-me-down pashminas. I think of my middle school days, as I prodded at my soft torso, the droopiness of my cheeks and couldn’t, for the life of me, figure out how to live in my body.

Policing is a word that makes me feel tense even as I type it, as if speaking it into existence will take me back to the moments I felt the most small. Policing is a stripping of love, safety and rationale. Surveillance culture breeds a competitive race into assimilation, a sort of survival of the fittest. Except there is no real winner. We are all deviants; those of us from countries sprawled across the global South and the forgotten corners of the Western world, the indigenous, the poor of us, the educated of us, those of us with little access. The visibly Muslim, the visibly Black, the visibly Other. The insecurity of the state becomes the insecurity of the personal. We change names, we struggle to attain higher education in spaces that reject us, we dress more conservatively, and we shed the same fabrics. We build communities which internalize the same violent notions of purity, of homogeneity, of heteronormative patriarchy and every “ism” under the sun. We watch each other. And yet, we remain the subject.

Asam Ahmad: I think there are two ways of thinking through surveillance culture: surveillance as interpellation (Fanon), as rendering the subject within a delimited and highly circumscribed ontological space, and surveillance as rendering visible the very antagonisms that will be utilized for the exercise and expansion of state power (Foucault). It’s not just that the state’s surveillance mechanisms interpellate us as subjects in highly specific ways; rather, those same mechanisms create and then disseminate ideas of who and what constitutes the enemy of a state. I think of the ways in which the figure of the terrorist is so incredibly indispensable to the (permanent) state of emergenc(ies) in which most western liberal democracies now find themselves in. (And here, I don’t even need to point out that the very term “terrorism” has come to only signify Muslim terrorists — this is the default definition that now circulates in most people’s minds. The word “terror” itself thinks for us in the very ways power wants us to think about terror.) One doesn’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to note, for instance, that ISIS originates from the actions of the US military industrial complex. But it wouldn’t be far-fetched to say that if ISIS did not exist, it would need to be manufactured anyway in order for the state to function and for it to exercise its power.

What about non-state surveillance culture? Where does state policing of Black and Brown bodies give way to communities policing one another in private and in public?

Alok Vaid Menon: I think about gender — and specifically the policing of the gender binary — as the internalization of surveillance culture by the South Asian communities that I grew up in. I think about how, as a trans and gender non-conforming person, I have little space to talk about how the brunt of the gender policing that I have experienced in my life has come from my own family and communities, regardless of their gender. And these patterns of intimidation, of punishment for certain forms of visibility, of regulation of dress, speech, behavior, choice feel inextricably linked to the ways in which the State has taught us to contain, categorize, and colonize. I think the danger becomes when we discuss this type of gender policing without also addressing the ways that the State has and continues to police racialized people — we run the risk of demonizing our own and participating in a white supremacist narrative that immigrants and brown people are “more homophobic” or “more transphobic.” We need a more complicated way of ascribing agency and pinpointing blame: “Yes this happens to me, BUT…”

Fariha Roisin: I agree so much with Alok. There are so many limitations on bodies in South Asian/Muslim diasporas. The constant fate of being slut-shamed by so many people I was close to — including my mom and my sister — was mind-numbing. Ironically, I think that’s why I was pregnant at eighteen; I was never able to accept myself as a sexual being, so I punished myself through actively placing myself in positions of danger.

Something I think of a lot is how often my mom would call me up, crying, exhaustively calling me a whore, or other things, saying how she was embarrassed at an event because so-and-so had said something disparaging about me, oftentimes about how “loose” I was, or how “bad an influence” I was. When I figured out that it was through people spying on me over social media websites I felt so violated. In response, I would always tell my mother that there are two sides to every story (which never helped) but I refused to say things that I knew about what other kids were doing because I wanted to end that cycle. I wanted to end the cycle where women police other women. Or South Asians police other South Asians. We forget how subversive our own actions of kindness are. There were so many situations where I could have deferred to somebody’s kid doing something “wrong” but I never did, because it was besides the point. As Alok pointed out, there’s nothing empowering about shifting the blame.

Having said this: I’m not sure people understand how vital it is to be kind. Which, I know, sounds so Pollyanna, but I am so tired of people being engaged politically but bashing others for their lack of knowledge. That’s a form of policing that we don’t talk about. How in our own black and brown communities we are constantly surveilling each other. I think people make a lot of offhand assumptions about other people’s lives and we have to stop — especially if we don’t know them and the judgement only fits a narrative that we’ve created about them. It’s a reactive way of silencing, and it’s not beneficial to us, as a larger community. We have to be willing to have conversations with each other. We have to stop judging ourselves and others.

I often think of how my dad would tell me how colonialism was a way to keep us servile, to diminish our capacities. The British came and split India (and the world) into pieces; we started wars with each other; we began to hate others like and different from us. So, now, how do we heal from that experience? How do we actively begin processes of decolonization? How do we, collectively, move forward? I think it’s by lessening the hate in our hearts. The revolution starts when we begin to engage through empathy. I can’t say this enough: we have to stop policing each other. We have to be conscious of how we reproduce state violence in our own communities. I tweeted this earlier this year, ha!, but I do think kindness is where the real revolution lies.

These days, I have so many South Asian or Muslim women write to me and tell me that they’re grateful for my speaking out because I refuse to live a double life. But (!!!) it took me years of self-imposed violence to refuse to live a double life. I experienced years of abuse from my peers, from my mother, from my partners, from myself, to get here. We have to make ourselves feel safe in these spaces, and I don’t always feel safe in spaces that are ostensibly for me, and that’s frustrating, but more than anything it’s isolating.

We are all complicated. We all worthy of love. I am a Muslim woman, but I also have sex. I am South Asian, and I am also queer. These things are not mutually exclusive. So much of what I do, and continue to want to do, is to give language to the liminal states that we live in. Through narrative we heal; through creating a voice we understand that we are not wrong; by loving ourselves, and others, we become whole.

Amani Bin Shikhan: I struggle a lot with the concept of living a “double life,” not in the physical, social sense of my life but in the internal dialogues I have on a daily basis. The theory of intersectionality is still one whose basics I revisit often, not necessarily to remind myself of its definition, but to remind myself that it’s okay to be complicated. I joke with my East African and Middle Eastern friends that shame is a prerequisite in engaging in our multitude of cultures, whether the involvement is active or passive in nature. It’s something that I struggle to undo in my most private of thoughts. I’m not sure how much of my connection to culture — and by extension, everything else I believe to be true and important — is dependent on being “better,” or stronger than the Western influences that are assumed on my mind and body, or smarter than the perceived shortcomings of the culture and people who gave me life.

I have a genuine fear of speaking to my loved ones about conversations that I know would be seen as taboo — gender and sexuality, mental health, etc. — not because I doubt their ability to ~get it~, but because I know that it can be extremely difficult to confront the fragility of your ideological truths head-on. My parents are my best friends; they’ve taught me the importance of community, education and spirituality to keep me grounded in the most tumultuous of times. Even then, I know that there are certain subjects that I dread talking about in their presence. I’m not sure if it’s because I don’t want them to see me as their child, dismissive of their beliefs or if I don’t want to get myself into a situation where the brightness of their light dims. Maybe this fear is warranted, maybe I’ve imagined the worst possible scenarios and scared myself into believing them to be unwavering facts. This is the violence of surveillance; it births hesitancy in every facet of life. It’s a strange feeling to feel as though you are at odds with your own self, and yet, there I find myself time and time again. Surveillance vis-a-vis the state is a truth that can be researched, debated and organized around by people who feel its ramifications similarly. Surveillance within smaller bubbles dealing with conceptions of faith, culture, gender and every other intersection is harder because of its intimacy, its ability to break your spirit.

Asam Ahmad: We can also think of the ways in which “we” — progressives, citizens, subjects — internalize the logic of surveillance culture as the only way for us to articulate our “real and authentic selves.” When Alok speaks of the unfamiliar as the suspicious, it makes me think of the very notion of “coming out” and how that functions to police bodies and sexuality in highly specific and historically contingent ways. If visibility for trans women, for instance, means violence or sometimes potentially even death, what does it mean to insist that people “come out” in order to be legible to us as members of our community? What does it mean to ask people who are already multiply marginalized to further render visible their marginalization? And yet, at the same time, I can’t help but think of Junot Diaz’ metaphor of monsters as beings who do not have cultural and social mirrors to reflect their selves back to them. It’s as if we are caught in an impossible catch-22 from which there is no beyond.

Do communities in diaspora replicate the violence of state surveillance? Where and how? If not, what is the relationship between state norms and the surveillance culture in our communities? Alok’s thoughts on inherited colonial traumas are useful here, thinking about how people of color can replicate violent structures they inherit. Is surveillance culture a modern day colonial inheritance? How do we think about it? How do you navigate these violences?) How can we resist this within our own communities?

Fariha Roisin: Absolutely, just as the largest propagators of the patriarchy are so often women. This is what’s so damaging, that they replicate and enforce these impositions with so much tenacity; with so much readied intolerance. It’s important to accept and move on, without indicting our communities, that are still in the process of unlearning — as are we. It’s been so vital to me to connect with other South Asian/Muslims because it’s nourishing to be seen in all of your multitude of complexities. If we can learn to forgive each other, by embracing the other, we also teach others to. This is also how we really revolutionize culture: by learning to love others, truly, with no conditions attached.

Amani Bin Shikhan: I’m not sure that there is a definite answer to any of the aforementioned questions. To imply that diasporic communities — in my context, Black Muslim immigrant girls and women — are perpetrators of the state is to imply that they can exert a power comparable to the power of the state. Within diasporic communities, yes, there are definitely ranks of cultural and religious ideals: The Model Minority is rarely poor, or Black, or gender non-conforming; the Liberal Muslim is rarely Black or a woman whose multiplicity isn’t glossed over for the sake of posterity. The head of state, no matter how much they try, will not serve as more than a reminder of all that kills people who share their identifiers. At most, I would say my diasporic community does not mirror violence of the state, but rather is still learning how to not pass down the trauma they’ve inherited, as both Alok and Farhia have put beautifully, and Rianna Jade Parker of the Lonely Londoners articulates wonderfully in an episode of Cecile Emeke’s Strolling Series. Like I said above, my parents are my biggest teachers, and I see the ways in which they carefully right the wrongs of their parents and the practices or thought processes that they have come to find outdated. We are trying to survive. We are trying to build something worth surviving for. It’s important to value ourselves and our communities enough to see them as imperfect and love them still.

Asam Ahmad: I sometimes think of the ways in which for me, queerness has often worked oppositionally from race/ethnicity when it comes to public perception and my ability to navigate different kinds of public space. I find myself sometimes exaggerating my queerness to erase my monstrous or terroristic race/ethnic significations. It’s almost as if queerness becomes the repository of the west and of the state, in that it works against race. This is terrifying, and ahistorical, to say the least.

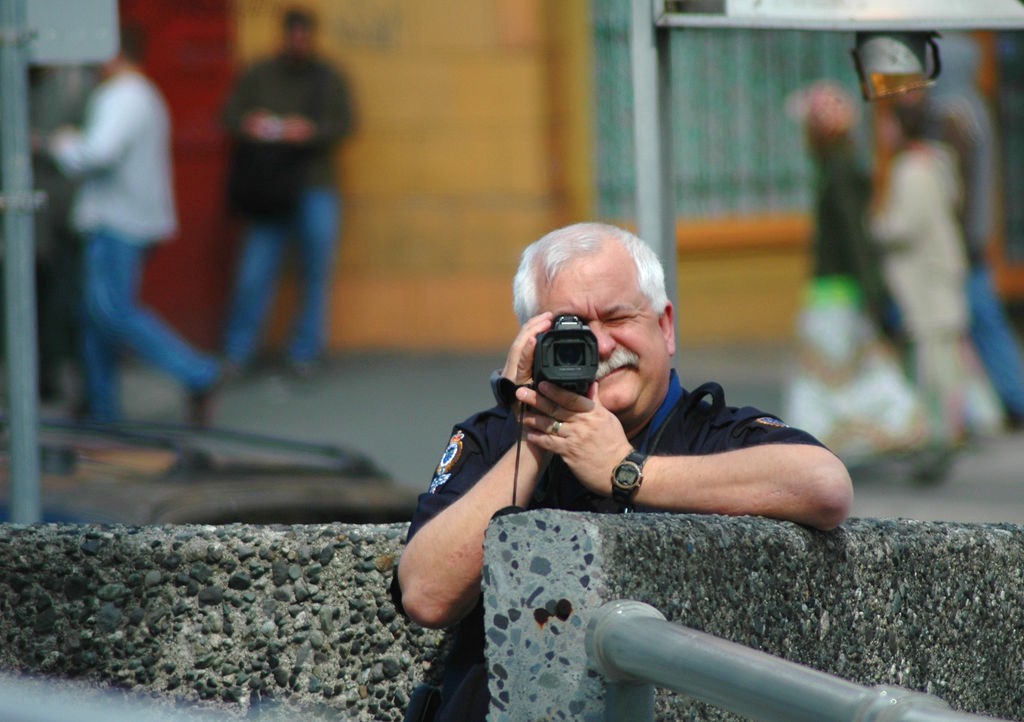

Photo by Pete