The Airbnb Endgame

Last week, the peer-to-peer hotel company Airbnb released a batch of anonymized data about hosts who rent out their apartments in New York City because it wants “more people to understand who we are, what we’re all about and how we help communities around the world.” With this data, what the third-most valuable privately held tech company in the world seems to want people to understand, most of all, is that Airbnb’s “community in New York is made up of hard working families in all five boroughs who, during a time of economic inequality, depend on home sharing as an economic lifeline.” Why, one might wonder, is a $25 billion company so outwardly interested in the fate of the urban working and middle classes?

Airbnb’s unusual brand of real-estate populism has only grown more pitched over the last year or so. Rather than advocating for Airbnb’s interests as an ascendant disrupter of a sclerotic industry, or a proponent of expansive private property or tenants rights, it is increasingly doing so as a representative, vis-a-vis its users, of an entire economic class actively struggling to continue to exist in the country’s most desirable cities (or at all). That case is being made both to policymakers and to the public. (And while other vanguards of the sharing economy are also occasionally a fan of the seasonally appropriate look — unlike Uber, whose original inspiration can be summed in an early quote from its CEO Travis Kalanick, “I am living in the future. I pushed a button and a car rolled up and now I’m a frickin’ pimp” — Airbnb’s origin story rings true to its save-the-middle-class message: It was, in the company’s mythology, born out of CEO Brian Chesky’s “own desperation of needing an affordable place to stay.” How relatable.)

Airbnb’s self-appointed role as a savior of struggling city residents was a key component of its recent successful campaign to defeat Proposition F in San Francisco — which would have, among other restrictions on short-term rentals, capped the number of days that a property could be rented at seventy-five days per year. But it is the core of Airbnb’s public messaging in New York City, where housing is a major political issue, and where the company faces pushback from government officials, landlords, and tenant groups, who variously charge that Airbnb has spawned countless illegal hotels, depleted housing stock, and driven up neighborhood rents — and who have succeeded in creating the real, if soft, perception that maybe, in some way, Airbnb is… bad for cities, or at least the people who are trying to live in them? More importantly though, New York is also where Airbnb is fundamentally incompatible with housing law as it currently exists.

To the extent that Airbnb has publicly addressed the dissonance between its interests, the law, and public perception — beyond repeatedly and insistently pointing out its economic value to cities — it has been most vocal about reining in so-called “bad actors,” who, it says, provide “a low-quality experience” or fail “to live up to the standards we set for our community.” These “bad actors” run the gamut from large illegal hotel networks to a random dude with five listings under different names to the couple who rented apartments just to Airbnb them to whatever monster crammed twenty-two beds into a single apartment. The rub is that working with the city to remove these caricatures of bad hosts is not a bold startup compromising and working within a brutal regulatory regime, as Airbnb characterizes it; it’s wholly in Airbnb’s interests, because such hosts make for poor optics, service, or both. (There’s no room for such operators in Airbnb’s grand vision for the future anyway.)

Accordingly, the company has worked hard to disabuse the public — and, presumably, the attorney general — of the notion that large swaths of the service’s listing are controlled by quasi-commercial operators motivated entirely by profit who, possibly illegally, siphon off precious housing stock that could be used by residents. In the blog post announcing last week’s data dump, Airbnb took care to emphasize that “90 percent of our hosts have indicated in a survey that the property they list is their permanent home,” “95% of our entire home hosts share only one listing,” and that “99% of all entire home properties listed on the platform are shared by hosts with one or two listings,” a far cry from what Jaron Benjamin of the Metropolitan Council on Housing described to Jessica Pressler last year in New York: “…property owners all over the city, having realized they can make more money on short-term rentals, have begun converting apartments into full-time Airbnb properties, resulting in their being taken off the market for full-time tenants and the further depletion of the already limited stock of affordable or even relatively affordable housing.”

What all of this posturing about bad hosts is meant to obscure is that the exact kind of hosting that Airbnb does want, what it envisions as the core of the service — thousands and thousands and thousands of regular people sharing their homes whenever they’re not home — is largely illegal in New York. Like actually against the law, up-to-$5000-fine kind of illegal! While it’s not uncommon for startups looking to “disrupt” something to begin operating in liminal legal spaces, the laws in New York surrounding short-term rentals are rather unambiguous, despite Airbnb’s protests that there is a “lack of clarity” around the rules. It’s illegal for a person living in an apartment in a “multiple-dwelling” — essentially, a building with more than two apartments — to rent out his or her entire home for a period of less than thirty days if he or she is not present. (It’s perfectly legal in single- and two-family homes, which aren’t “multiple dwellings.”) So, a whole-home listing in a building with more than two apartments that doesn’t have a minimum stay of thirty days — and isn’t a hotel or boarding house or some such — is probably illegal.

Late last year, when Attorney General Eric Schneiderman took stock of Airbnb listings, his office found that some seventy-two percent of whole-home rentals appeared to be in violation of the law. More striking was that, according to the attorney general’s report, “six percent of hosts dominated the platform during that period, offering up to hundreds of unique units, accepting thirty-six percent of private short-term bookings, and receiving $168 million, thirty-seven percent of all host revenue.” According to the data that Airbnb released last week, fifty-five percent of active listings on the service are whole-home listings — including sixty-four percent of listings for what it calls “Outer Manhattan,” and sixty-three percent of listings for “Central Manhattan.” Any of these listings that don’t require a thirty-day stay and aren’t in a single-family or two-family home, or in a building properly classified for “more or less temporary abode of individuals or families,” are probably illegal. Only eight percent of entire-home listings in New York require a thirty-day stay to comply with the law — and such listings generated just two percent of the revenue associated with whole-home shares, to borrow Airbnb’s language, suggesting they made up a vanishing small portion of Airbnb’s bookings over the last year. It seems wholly unlikely that ninety-two percent of Airbnb’s entire home listings in New York City are for single-family or two-family houses or in proper boarding houses or hotels (though some are!), so one could reasonably infer, as the attorney general’s office did a year ago, that many of Airbnb’s entire-home listings remain illegal under the current law.

Whatever one’s opinion of the current short-term rental laws in New York may be — they’re certainly intense! — it is remarkable how Airbnb treats them, in both rhetoric and practice. While fine print at sign-up (and a FAQ) warns hosts about the Multiple Dwelling law, Airbnb does not generally acknowledge how thoroughly the law cuts across its listings, and when it does, it does so tacitly, by repeatedly calling for “fair rules for home sharing” or as it did in response to City Councilwoman Helen Rosenthal’s proposal to increase fines for breaking the law: “Helen Rosenthal’s solution would be to fine middle class New Yorkers $10,000 while they are just trying to make ends meet. We think a good policy solution is to try to help regular New Yorkers have an economic lifeline. We look forward to working with the city to put middle-class New Yorkers first.” That it has taken no immediately apparent steps to curb such listings — and has actively fought against giving the city what it needs to do so, according to city council members Rosenthal and Jumaane Williams — makes it clear that it has no interest in removing these kinds of listings from the service. And the efficacy of Airbnb’s overall strategy to legitimize such mundanely illegal home sharing is revealed in how not-taken-for-granted it is that so many of its listings violate the law; for example, the initial version of the New York Times first story on last week’s data release did not mention anything of the sort.

Transparency, or the performance of it, is no small part of this legitimization effort. And it is largely a performance, according to both city council members and the attorney general. Even when Airbnb said that it was “making available 170,000 rows of data about almost 60,000 listings in our community in New York City” it did so in a manner designed to be as inscrutable as possible. The full dataset, even though it was anonymized, was not released publicly. Reporters had to make an appointment to see the data, which could be only viewed on a laptop without an internet connection while being watched by Airbnb employees. Reporters were not allowed to save the data or take it with them to conduct in-depth analysis, but forced to write down what they could with a pencil and paper (though at least one reporter was allowed to take a photo with their phone with the promise of not publishing it). More subtly, some of the dataset was clearly architected to obfuscate the impact of its most prolific and profitable hosts; it presented the median of certain metrics from November 1st, 2014 through November 1st, 2015, rather than the mean (or average), effectively hiding its biggest numbers.

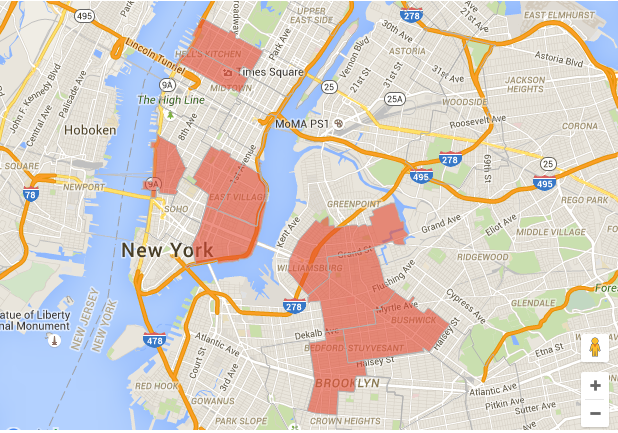

Most active zipcodes, according to Gawker Data

For instance, while it’s nice to know that the median annual supplemental income for a New York City host is just $5,110 — clearly just a regular joe! — and that, as the Gawker Data Team’s Josh Laurito points out, even in Times Square, the top zip code, the median income is under $10,000 — it only means that half of the hosts in the dataset were earning less than that, and the other half were earning more. Being able to compare the median with the mean would more clearly indicate what kind of money superhosts are making. (Which is potentially a lot!) Given that hosts with three or more listings are a minority — in the November 17th snapshot data, they made up just over one percent of all active listings — yet they generated around twenty-five percent of the revenue associated with entire-home listings over the last year, one can reasonably infer that the mean would be higher. (And let’s not forget how easily the Times found a host with five listings under five different names who was earning some half a million a year.) Worse, perhaps, Ben Popper reported, some of the data summaries appeared to contain mathematical errors. (Still, some useful data emerged from the release: According to our analysis, at least sixteen percent of homes were booked for more than a hundred and twenty days last year; 9.2 percent were booked for more than a hundred and eighty days. It’s possible that some of these listings were licensed bed and breakfasts, though without more precise data from Airbnb, it’s difficult to tell.)

All that said, there’s little reason not to take Airbnb at its word that by next year the vast majority of revenue earned by whole-home shares — some eighty-six percent of it — will be earned by hosts with just one listing, who may be, by and large, members of the middle and working class. The great irony of Airbnb, though, is that the individuals in the best position to utilize the service in order to make extra money to simply stay in their homes — those living in the neighborhoods and kinds of homes most desirable to tourists — are the ones most likely, as the company puts it, to need an economic lifeline “during a time of economic inequality” as rents soar all around them. One might ask Airbnb what mysterious conditions, it thinks, have lead to this “time of economic equality” — well, macroeconomics for one — and how it seeks to alter those conditions (or create fundamentally new ones), given that they are largely favorable to its enterprise: More people who need more money means more listings. (Few startups have user motivation quite as powerful as looming financial ruin.)

Part of that answer was given by its head of global policy, Chris Lehane, who hailed what the company does for the middle class — allows them to convert their homes into a new kind of asset from which, with Airbnb’s help, they can extract value in order to maintain or marginally improve their class positions in cities where those positions are increasingly tenuous — as a “broader evolution in capitalism.” But that can only take place if the laws around home-sharing in New York (and wherever else there are legal issues!) are changed in Airbnb’s favor. Which the company seems to be betting will happen, through the force of its lobbying — ready the GUILDS — or its broader efforts of legitimation, or the natural progression of how we think about tenancy and private property, or whatever. And we sort of know what that regulatory regime would look like for Airbnb, given the kinds of home-sharing rules that it says would be agreeable in New York:

Create rules that allow New Yorkers share only the home in which they live. Current law prevents many people from sharing their home unless they are present. We need thoughtful laws that let New Yorkers share only the home in which they live, while preventing abuse. … Fix the law to help New Yorkers who need it most. If your apartment is rent-regulated, you often can’t share your home, even if you are present. Home sharing is an economic lifeline for thousands of New Yorkers. These New Yorkers should be able to share their space as long as they do not earn more through home sharing than they pay in rent.

These are rules which redefine some current notions of private property and tenancy and real estate regulation. For instance, what does it mean to be a landlord and to own property if your tenants can infinitely sublet it? What does it mean to be a tenant if you Airbnb your apartment half of the year? Who knows? But redefining private property rights: How ambitious!

That level of ambition is, of course, precisely why Airbnb is valued at $25 billion by its investors (or, to use another example, Uber is valued at $62 billion). As intently as CEO Brian Chesky frames the company as being in the travel business (and that may be true!), a maximal Airbnb in which everyone is sharing their home so that “every person in every country can stay with someone on Airbnb,” as he once put it, is, in effect, a privatized property allocation platform. Which, admittedly sounds not a little ridiculous — after all, that’s… sort of like a state function currently performed by city governments? — but what else does Airbnb’s valuation, rhetoric, approach to regulation, and political organizing suggest? Nothing less ambitious than that, anyway.

Additional data journalashgjkhasgj contributed by Brendan O’Connor.