The Bird's-Eye View

Earlier this month, in a blog post titled “Hard decisions for a sustainable platform,” Twitter announced a small product change that has altered, in a subtle but widespread way, the way you read/scan/judge/subconsciously process Things On The Internet:

Recently, we announced a new design for our Tweet and follow buttons, as well as a deprecation of the Tweet count feature. We expect to ship these changes by Nov. 20, 2015. We wanted to take a moment to explain how and why we made this decision, as it reflects the kinds of engineering tradeoffs we make every day.

This change concerns those little buttons on top of, under and beside a great number of pages online — the ones that tell you, at a glance, how many people have already shared a story on Twitter. They usually sit next to a similar button linked to Facebook.

Together, these buttons — with occasional share counts from Pinterest and others — have become something like a public ratings system for the web. Years ago, some sites put view counts next to posts, which, among other things, seemed to have an amplifying effect for already-popular stories. Some still do. But later, share buttons encouraged, and then standardized, a similar sort of behavior across the web, albeit on outside parties’ terms. Their ubiquity helped share counts overtake view counts or, more commonly, comment counts as the most visible signal of a post’s popularity.

Twitter’s reasons for changing its buttons and cutting off third-party counters are: “it doesn’t count replies, quote Tweets, variants of your URLs, nor does it reflect the fact that some people Tweeting these URLs might have many more followers than others;” the “count API” was never officially public; back-end tech changes; etc. Additionally, its post notes:

The count was built in a time where the only button on the web was from Twitter. Today, it’s most commonly placed among a number of other share buttons, few of which have counts.

So perhaps Twitter decided that millions of pieces of content on which a Twitter logo with a smaller number set next to a Facebook logo with a much higher number wasn’t doing them any favors. (The numbers aren’t quite comparable, so why make them so easy to compare?) Or maybe it’s interested only in sharing a more thorough and flattering figure. (This sounds sort of like the opposite of a hard decision. Almost like an inevitable one!)

Or maybe this tiny change is of a piece with other changes to the Twitter platform, recent and less recent. Twitter let developers run wild with mobile apps, bought one of them, then marginalized the others. Twitter gave people and companies space to build photo sharing and link shortening apps, some of which became large businesses, before creating its own. Twitter gave people tools to embed tweets on websites, which they used to figure out how to cover Twitter and the conversations happening on it; Twitter then started curating collections of tweets within its app, in styles created by its partners. Twitter is good at giving people enough space to figure out new things. It’s also shrewd about deciding which of those things it should roll back up as its own. (A secondary consequence here that won’t affect most users directly: various analytics services, which publishers and others use to track their posts as well as posts from other sites, will simply no longer support Twitter.)

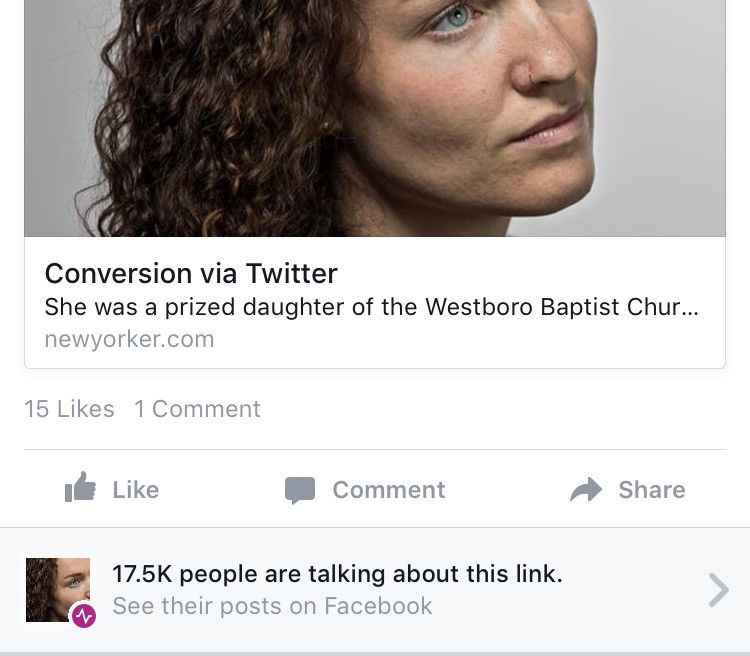

In recent months, Facebook has been showing users something new: a tally of how many people are talking about a particular link or story across the service.

This is the type of change you get used to quickly. But it’s notable that those numbers never before existed inside Facebook — from the outside, in an article, you could see how many people were engaging with it on Facebook. From inside Facebook, you only saw how many people were sharing a particular instance of the link. Previously, this data was most interesting from the outside; now, on Facebook, the concept of “outside” is less important verging on irrelevant. Perhaps Twitter is thinking something similar.

Why privilege an outside vantage? Why not turn those countless disparate numbers, displayed in all kinds of different ways and for different purposes, into a tidier Twitter rating to be shared and deployed at the company’s discretion, be it widely, carefully, or, whatever, who cares, not at all? After all, according to Twitter’s CFO, the service’s audience is bigger than Facebook’s “depending on how you look at it.” So why not control how you look at it?