WeParty Like It's 1999

by Brendan O’Connor

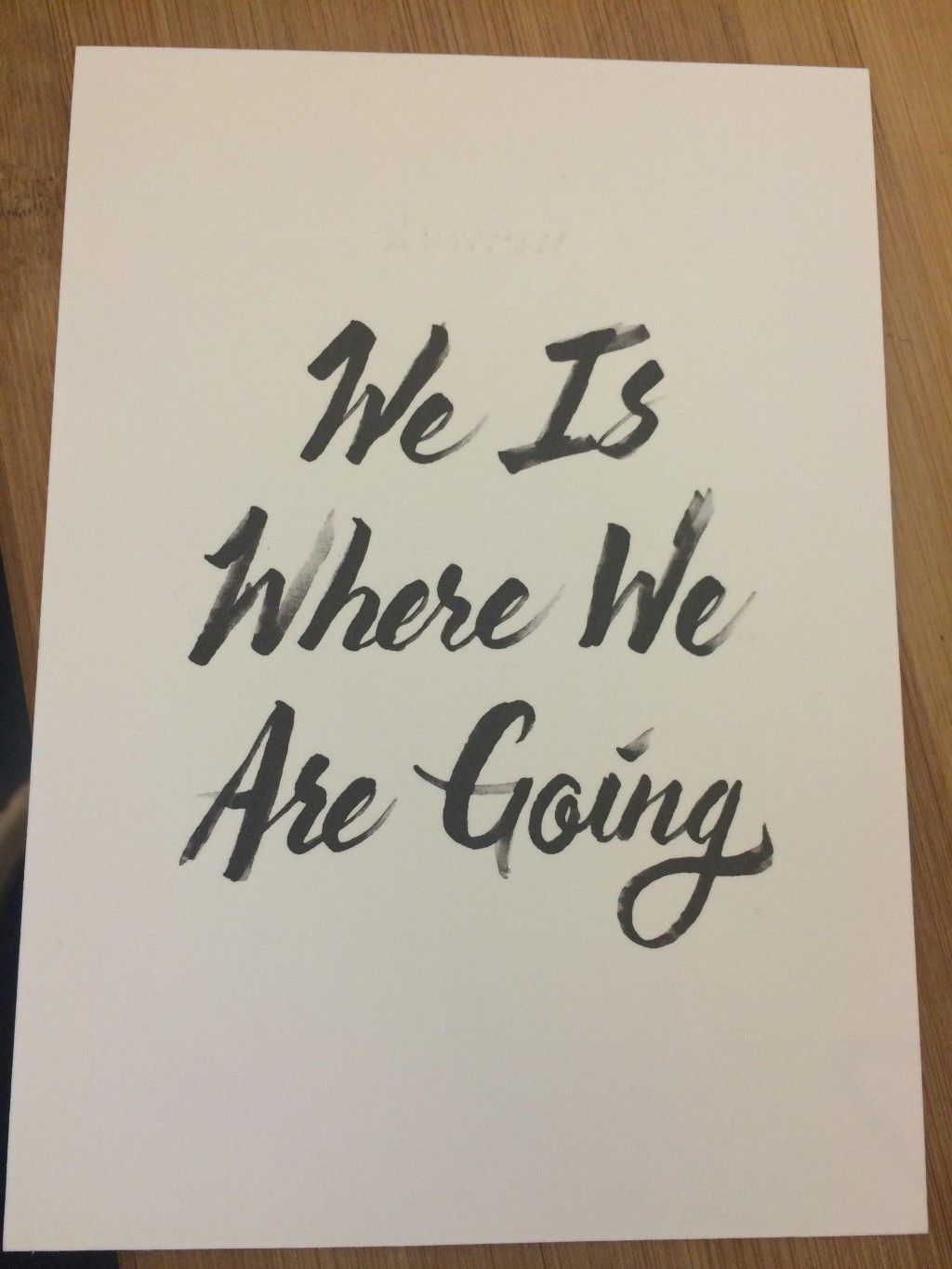

Last week, members of WeWork, an office-space concern based in New York City and most recently valued at ten billion dollars, were invited to an event on Tuesday, at 7:30, on the fourth floor of WeWork’s 18th street location. “We Is Where We Are Going,” the front of the invitation read. “We invite you to help us build something new — a home for people who join as ‘me,’ but become part of a greater ‘we.’” It seems likely that this event — which was already pretty bumping by the time I arrived, around 7:20 — concerned WeLive, WeWork’s expansion into residential development.

WeWork’s original business model is to lease office space from traditional landlords, renovate it to appeal to the aspiring entrepreneurial class (think kegs, ping-pong, and lots of couches for sitting on your laptop), and then rent it to them at prices significantly higher than the surrounding market rate. With WeLive, WeWork hopes to collapse any remaining distinction such people make between their work and their life, offering living spaces in the same building as their co-working office spaces. According to financial statements provided to investors last year and obtained by BuzzFeed, WeWork expects that WeLive — which has not yet launched — will supply twenty one percent of the company’s overall revenue by 2018, bringing in over six hundred million dollars in annual revenue after three years. As BuzzFeed’s Nitasha Tiku points out, however: “Much like WeWork’s office-rental arm, projected earnings from co-living depend on a steady stream of customers willing to sacrifice privacy for proximity to like-minded people.”

WeWork’s first slated WeLive location in New York, 110 Wall Street, is a building heavily damaged in Superstorm Sandy, owned by Rudin Management, one of New York’s largest development firms, and apparently leased to WeWork in its three-thousand-square-foot entirety. (WeWork is also partnered with Rudin in the development of a six hundred seventy-five thousand square foot pile of boxes in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.) In the elevator riding up at the 18th Street location on Tuesday, one of my fellow passengers remarked to his friend, “Dude, we’re gonna be neighbors.”

“I should probably tell my wife about this,” his friend replied.

“Does she not know?” the first guy asked.

“Well,” the second explained, “she’s overseas. We FaceTime.”

On the fourth floor, WeWork employees at a desk took people’s names as they stepped off the elevator. To the left, beyond floor-to-ceiling glass doors, a large, open room full of people enjoying post-happy hour drinks smiled and laughed. Loud music played. “Are you on the list?” I was asked. I was on the list, having emailed to RSVP. “Oh, I see, you still need to sign an non-disclosure agreement.” Hmm. Why is that necessary? “Confidential information.”

Two people who had signed the NDA were ushered through the glass doors and offered drinks. A WeWork employee suggested I take a copy of the NDA and look it over. I took a copy and pretended to look it over while texting my editor about whether I should sign it. “Follow your heart lol,” he concluded. I said thank you, and got back in the elevator.

As the doors closed, I heard a woman who had appeared to be a supervisor ask an employee with the list of names, “Did he argue with you?”

“A little,” was the response.

Anyway, I’m told that the apartments atop 110 Wall Street come fully-furnished, will rent for between five hundred and seven hundred dollars per month for a small studio, that rent goes up fifty percent after the first six months and a whole lot more after the first year. According to market analysis conducted by MNS, the average rent for a studio apartment in a building with a doorman in the Financial District was just over three thousand dollars per month. So, depending on where WeWork rent ends up, that could be a pretty good deal — although, as Tiku points out, the projected rents do not include WeLive’s “services” fee, which will double to one hundred dollars a month by 2018. I’m also told that residents have to be directly associated with a member of WeWork (i.e. in a three-bedroom apartment, one has to be a WeWorker), and that there is, apparently, a bar in the laundry room.

Asked to confirm or deny any of this, WeWork declined to comment.

In its prospective residential offerings as in its commercial product, WeWork’s core innovation — and the sharing economy’s writ large — seems to be not, in fact, in making things more affordable, but rather in coming up with new ways to obscure where the true costs lie.

On Thursday evening, WeWork threw another party — this one less informational and much more fun. It was billed as a “warehouse party,” but it was in DUMBO (or “Dumbo Heights,” as WeWork calls it), at WeWork’s newest location — its first in Brooklyn. “Pizza and Hip-Hop” was the theme. The location opened in August, but the space the party took place in was spare and unadorned. (Almost like a warehouse!) The party was full of people attractive in the way that photographs well for, oh, I don’t know, investors? advertisers? Instagram? which is another way of saying, if not attractive, at least well dressed, mostly.

There were a lot of carefully-crafted beards. There was a high concentration of man buns and a higher concentration of high-and-tight haircuts, though not so many to the degree of Brad Pitt Nazi-Killer. Here and there, some streetwear. Drake’s latest hit, “Hotline Bling” came on. “That’s that Toronto shit,” someone remarked. Later, an earlier Drake hit, “Back to Back” came on, and people rapped.

As I navigated my way through the crowd looking for pizza, a blonde woman stopped in front of me. “You look lost,” she said. Was she a member? An employee? It was unclear. In any case, she wasn’t exactly wrong.

Before Q-Tip played, WeWork’s long-haired Israeli co-founder and CEO Adam Neumann, wearing a grey t-shirt with the word “Creator” in all capital letters emblazoned upon it, made a short speech.

“This is a Brooklyn brand. The brand started here,” he said, which is only sort of true — Neumann, along with WeWork co-founder Miguel McKelvey, originally launched a co-working space business with the (somewhat shady?) Brooklyn landlord Joshua Guttman called Green Desk, in 2008. Guttman bought Neumann and McKelvey out in 2009. “As soon as we could come back, we did,” Neumann said. “It was illegal, but as soon as it was legal, we came back.” (Quite honestly, I’m not sure what he meant by this.)

“I travel all over the world. This is the center of the world. The people, the beer, the energy. It all comes from here. It’s the Brooklynization of the world.” The crowd cheered. Adam ordered that more shots be handed out. The crowd cheered again. “Whatever you want to do, the world will help you do it. You will raise investors. Whatever you want to do, whatever God wants you to do, whatever the world needs you to do, you will do it, because each and every one of you,” (here, he pointed to his shirt) “is a creator.”

I tried to catch Adam, who has previously referred to his company as a “capitalist kibbutz,” as he left, but I guess I picked the wrong exit to stand in front of, because I didn’t see him leave. Having missed out on the pizza, I followed suit shortly thereafter. I’ll just have to catch Q-Tip another time.