Twitter Thanks You For Your Service

There are two stories about Twitter that are really just one story told from two different points of view. There’s the Twitter that studies its users, observing their habits and formalizing their behaviors into features. This is the Twitter that turned manual retweets into a button; the Twitter that watched its users use hashtags and then turned them into a core feature of the service and a part of the language of the entire internet. Then there’s the Twitter that invited app developers to build apps for iOS, Android, Windows and Mac OS, before eventually either acquiring or building native apps of its own, allowing developers to live but explicitly marginalizing them, in some cases out of business.

In both stories, Twitter is a rational party acting in its own best interest — it didn’t need to defend itself because it could correctly say, in most cases, that it was making Twitter a more effective product. The difference lies in the distinction between a user and a partner: a party that gives and takes time and content and a party that actually turned what it gave to Twitter, and what it took back out, into money.

Here’s a third version. In 2011, Twitter introduced embedded tweets. This too was an observed behavior — Twitter screenshots had been showing up in web articles for years, and third party embedding services were growing. The announcement blog post laid out the official rationale:

Every Tweet has a story that’s more than just 140 characters. It has an author, mentions @people and #topics, contains media, and has actions you can use to share or join the conversation. It’s a dynamic piece of media, and we believe that everyone should be able to view and interact with Tweets on the Web in the same ways you would from any Twitter client.

So began a strange and fruitful era of Embedding Things From Twitter: posts aggregating loathsome responses to news events; posts using tweets as kicking-off-points for arguments; posts embedding tweets to display the expensive media contained therein; posts making sense of breaking news stories by linking together tweets and other media. Tweets, it turned out, were useful tool for the web, as little modular content units. All the while, less visibly, Twitter provided an ambient news and information context from which all kinds of news was consumed, written and published elsewhere. (Non-video embedding thrived for these few years of exploding traffic and awkward tension between platforms and websites. Instagram, Quora, Imgur.)

Four years later, Twitter is making arguments about how its audience may actually be bigger than Facebook’s, “depending how you look at it.” CFO Anthony Noto told a Deutsche Bank conference last month:

We have other audience numbers that no one talks about. If you add them up, it’s a big number. In fact, in some scenarios, you could argue that it’s bigger.

He’s referring to people who see tweets outside of the main feed: on TV, for example, or on the main page while not logged in. Or they see the tweets embedded elsewhere, in thousands of stories viewed by millions — or, Noto seems to suggest, billions — of people.

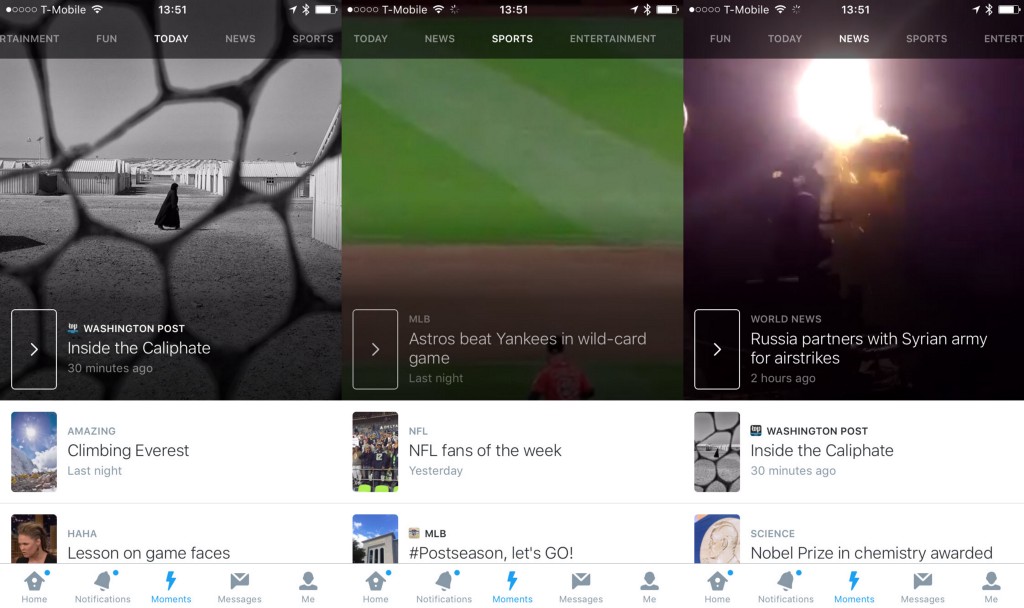

Twitter’s Moments have been characterized as a way for Twitter to reach an audience of people that might otherwise not use the service at all — a sort of Silent Majority of non-users who would appreciate Twitter if only they could approach it from some as-of-yet undiscovered angle. This might sound like wishful or even delusional thinking, to assume that your service is so good that the reason more people don’t use it is because they’re just confused. But it’s less ridiculous if you’re talking about people who you already claim to have a relationship with — those vast crowds of people who see tweets all the time, just somewhere else.

Twitter watched countless websites turn its tweets into Extremely Monetized Content. Now, it’s trying to figure out how to do some of that job itself. Its version of a publication is privileged on both ends: its aggregators have a fuller view of Twitter than any user; its viewers can see it in fewer taps and through a nicer interface than any story linked from within their timelines, AMPed or not. It’s not quite like when Twitter pushed out app developers, though the manner in which a number of apps have survived is probably instructive. Nor is it quite like when Twitter elevates a user behavior into a feature, though the instant wide use of those features is instructive as well. It’s closer, maybe, to the third, lesser-told version of Twitter’s inevitable platform consolidation: The dozens of link shorteners made redundant by t.co; the TwitPics and Yfrogs made to seem like spam by Twitter’s own image hosting. But it’s not quite that, either — that is, if we grant that the Twitter platform really is much larger, and looser, than previously imagined. Which… lol?

Moments is currently a minimalist curated scan of what Twitter is talking about. Not all of Twitter. Moments is not a window into Twitter’s many cultures; it is precluded from going meta or self-referential in the way Twitter users so often do, and which the feed-focused version of the service encourages. It is a standardizing, gentrifying force; if it favors one Twitter culture, it’s the Twitter of brands — that is, the Twitter that gets recommended to you daily via email if you sign up, follow nobody, and leave. This is Fallon country. We’re building from there.

As for internal categorization, like a publication it is divided into verticals, assembled by humans — some (many?) of whom worked previously as editors and aggregators at websites. It even has editorial guidelines! Under the header “BIAS, ACCURACY, AND STANDARDS,” Twitter says:

Individual moments should be free from bias. We will use data-driven decision making when choosing Tweets around controversial topics, and highlight the Tweets already receiving the most engagement on Twitter. On topics which reflect public debate, we will select Tweets that represent all sides of the argument or story where feasible. Twitter should not advance its own viewpoint, but rather reflect the discussion as it appears on our platform.

Actually, it’s about ethics in Twitter curation, the post does not quite continue, but may as well. That these are impossible guidelines is a hint at a coming conflict that I’m not sure anyone has quite figured out: as publications assimilate into platforms, and as platforms, in an effort to capture some of the energy and attention garnered by said publications on their turf, attempt to redefine the role of an editor/curator/reporter in terms that are most beneficial to them, we’ll have to re-litigate old arguments about control, bias, voice and balance, with higher stakes and less of a sense of accountability; the defendant, now, is simply insisting it isn’t liable. A first look suggests that the Moments approach to editorial judgement is learned, too: Its vague and primitive sense of what is and isn’t political (I’m sure opponents would challenge the unquoted “right-to-die” language here, for example); its implicit distinguishing between explicitly supporting or criticizing something, which is bad, and merely celebrating it, which is… fine?

Is Moments good? I don’t know. A sports “Moment” made sense to me; a collection of hashtagged Vines was both crammed full of Vine’s most popular and most irritating characters and also managed to be almost completely white; some posts read like volunteer branded content, which you can both complain about and recognize as a characteristic reading experience of this moment, but which suffers tremendously from lack of context. Exuberant celebration of consumption, branded or not, shares well. Aggregations of the celebrations serve no function, culturally or mechanically, inside Twitter.

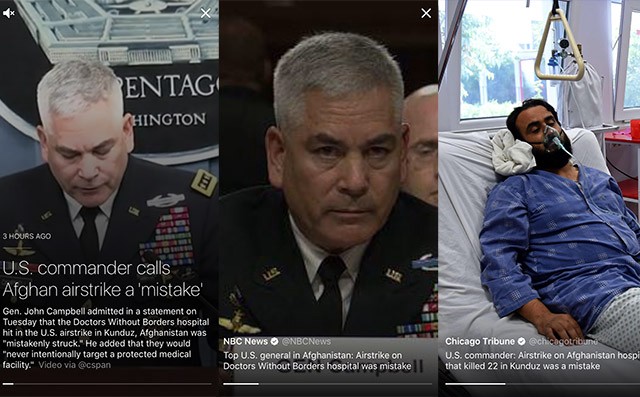

There is no scenario in which a selection of Twitter posts gathered together to tell a story is both compelling and without a point of view. The result looks like this, which…. what have I gained by scrolling deep here? What more do I know about this horrible story? Even if it did implore me to find out more, it doesn’t give me an obvious path to do so.

Creating a publication at such a high tier within a platform is almost too obvious an idea. A publication of publications must be better than any single one, right? A view from above is wider than a view from the ground, or something? That’s sort the idea behind Reddit’s Upvoted site, which has none of the material advantages of a feature-level publication like Moments but which at least has a coherent audience — or a few — to which it can cater. Moments has a much more diffuse audience, which is either its problem or its point, depending on what Twitter wants from it, and how it changes. A broad Aggregator Of Record that treats Twitter as its source is an appealing idea in the abstract, and I suppose could be made into something that seems worth digging into — a sort of approachably massive constant archive to compliment the timeline’s approachably chaotic churning context. But no publication has been able to thrive on Twitter, or on any social network, without understanding the way its posts relate to users’ identities, politics and self-image. The concepts of neutrality and balance are, in the context of Twitter, much less about rules than what they allow posters to project about themselves to their followers. Moments does not operate in that space, it skims from it.

Maybe Twitter finds a way to customize Moments — to aggregate or produce enough content-of-content material to shove tailored things in front of people that they’re more likely to interact with in a way that we will faithfully equate with caring. They do it everywhere else, why not here? (POTENTIAL NEW TWITTER SLOGAN? Twitter: Why Not Here.) This was the original plan, I think? So maybe they just need some time.

You can already see conflicting pressures: between the arbitrary standards Twitter has set for Moments, to be “even-handed,” and what actually gets you to swipe to the end. It’s easy to perform something that looks like balance on a story most readers, or curators, haven’t engaged with before, or often. But what happens next time someone walks into a crowded room with a loaded gun? Who is left reading that story without a powerful sense of what it means?

The Moments that make the most sense in the current configuration often inhabit a celebratory-but-somehow-not-”biased” space. All-Day Breakfast At McDonald’s Starts today? How fun, I love McDonalds, and so can you. Celebrating Twilight’s 10th Anniversary is a fun activity for people who have positive feelings toward Twilight. I’m sure the Moment aggregated around The Oscars, which are implicitly Good, will be effective. What’s entertainment? What’s news? Twitter: Welcome to the slippery slope of editorial guidelines! Everyone is very angry here, always.

Twitter isn’t the only platform trying to figure this out right now — the temptation for a platform to create a feed of feeds, a publication of publications, or some kind of god-mode consumption device is strong. Instagram’s curated tags are less explicitly newsy but absolutely compete with publications that use Instagram as a source. Snapchat’s Live Stories have no embedded Snapchat to compete with, which makes things easier for them, and content partners are relegated to a different tab. The temptation to create a new space between your platform and your hundreds of millions of users must be powerful. There’s an element of corporate fantasy here: what if all these people were our audience, not each other’s?

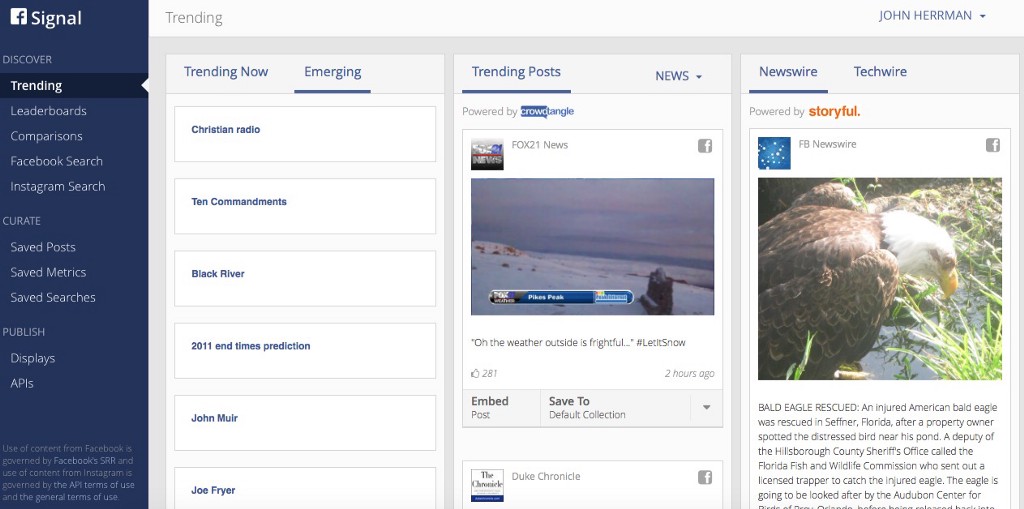

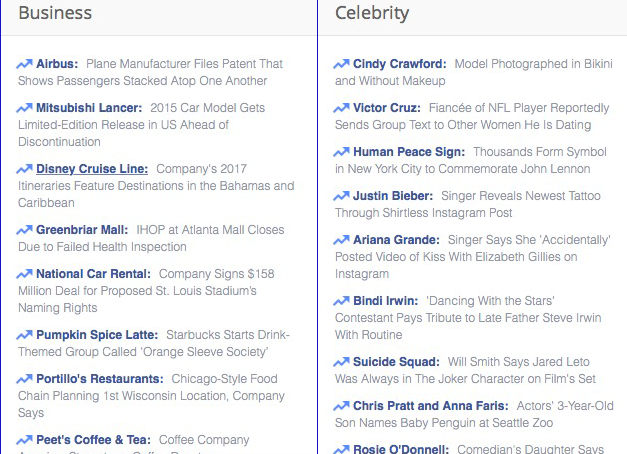

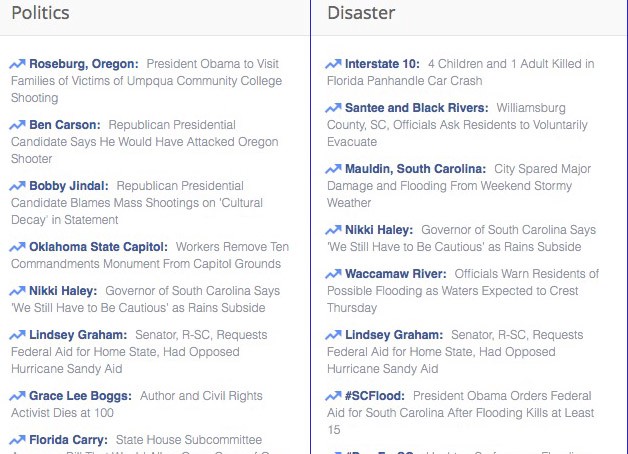

Facebook recently released Signal, a tool that gives reporters a top-down view of what’s happening on the Facebook and Instagram platforms. It’s a sort of infinite trending topics screen, and it feels powerful, though reporters have struggled somewhat to figure out what to do with it, beyond what they did with prior tools like Newswhip and Crowdtangle (on which Facebook Signal is based). That is: aggregate the hell out trending stories that aren’t yet spent. It’s also a depressing reading experience, both overwhelming and yet somehow dishearteningly narrow. Some screenshots from the second I finished typing this sentence, sight unseen.

Facebook, with a small team of editors, could turn this information into an app-level publication with no problem at all. They haven’t yet, unless you count Paper, which dealt with many of the same challenges Moments will face without the benefit of showing up unannounced in the middle of everyone’s primary Facebook apps and just staying there, begging to be read. Maybe they’re under less pressure to do so — shareholders aren’t constantly worried, they haven’t been leaderless for months, activist investors haven’t been going on TV telling them they’re morons. Or maybe they just know better? Signal is Facebook minus context, and Facebook is all about context. Post and videos that do well on Facebook can look utterly bizarre elsewhere — they’re meant to be wielded as expression of identity according to Facebook’s definition of the term. The curiosity gap is pointless in a vacuum.

Facebook is also, despite Twitter’s attempt at a frame-shift, a much larger service in every important way. News is just one more thing people get on Facebook, for now.

The intent of Moments, according to Twitter’s guidelines, is to create “the best experience possible for both consumers of content and those whose content is featured in Moments.” It will no doubt be exhilarating for individuals to have their posts featured in popular Moments, assuming, that is, they know — tweets aggregated into Moments are stripped, at least at first view, of all interactivity. There are no links; favorite and retweet functions are concealed behind a tap. This will be especially concerning to publications, who, absent the level of traffic Facebook sends, have come to love Twitter for other reasons, direct interactivity among them.

Moments is an attempt to annex territory carved out by publications. It represents power intentionally creating redundancy. This is explicit in the service’s terms:

We do not duplicate curated collections or sets of Tweets embedded on a single third-party website, or those retweeted from a single Twitter account.

Twitter will not rip off other curatorial efforts, in other words, with its own. This is necessary to mention because it might be tempting. Twitter curation has been observed as a successful Twitter strategy, and now Twitter is doing it too. Politely!

With each annexation Twitter creates a feeling of betrayal. Programmers and developer types were a major force in early Twitter; the acquisition of Tweetie and subsequent constriction of developer options inspired uproar and even a competing service, App.net, which was advertised as developer-centric. But the developers had served their purpose — Tweetie was turned into the Twitter app, and Twitter grew. The developers still tweet, but few of them are still making money from Twitter. They’re just users again.

If developers overestimated their worth to Twitter, so have journalists and the companies they work for; the same people who wrote Twitter’s previous power narratives. In their capacity as indirectly compensated professional Tweeters, journalists have — extremely unevenly — made Twitter a better place to keep up with not just people but… things?

They — we — did this because of a temporary alignment of goals. Twitter had a network, and tweeting helped you gain access to it. Performing the identity of a reporter or pundit on Twitter helped you gather a following; doing the work of reporting or punditry helped drive that audience to a site, which maybe sent you a paycheck. Twitter asserted itself as such a vital tool for news that ignoring it wasn’t an option, but also felt like an opportunity: to build and maintain and eventually monetize an audience of extremely interested people. A constantly expanding platform is an intoxicating context; it creates within itself a simulation of its own extreme growth and infinite potential, and the corresponding feeling that it will all culminate in some sort of exit or victory. Individuals and organizations sought opportunity in Twitter’s walled market, finding audiences of millions by curating and re-centralizing the bountiful products of Twitter’s vast and productive chaos.

But enough success on another company’s platform eventually, perhaps inevitably, represents to that platform a problem to be solved, an opportunity left to someone else, or at least an activity under-supervised. In a bottom-up Twitter, CNN’s millions of followers across multiple accounts are a triumph of news aggregation and Twitter utility; from the top down, they’re the best of a duplicative bunch, perhaps most eligible to be included in Moments, but most useful as an example to be learned from and maybe replaced.

Victory, for a publisher, is reduced to the ability to ask for partnerships, or for mercy, and the ability to secure them for a time. The space they inhabit is no longer open and ever-expanding. There is no Moments “strategy” for a third party without Twitter’s full and constant cooperation.

If there is comfort for publications here, it’s in Twitter’s lack of curatorial and — this may matter eventually — reportorial expertise and flexibility. Twitter knows it has a network, and it knows they like to look at stuff, and it knows there’s an opportunity in supplying that stuff, but that’s about it. There is a conceivable future in which Twitter, and other platforms, decide that the ability to create a Moments-like product doesn’t mean it’s worth the resources or liability, and they cede some control — of the editorial product, not the platform in general — back to partners who are better equipped to make the most of it; it’s already letting some organizations create and submit moments of their own. It works for TV, sort of! Comcast and Time Warner only directly produce some of the programming in their cable packages. Or more recently: YouTube partners with thousands of video producers, but doesn’t seem to want to render them obsolete. Production is risky and expensive; better, in their minds, to leave it to others. How sad when they fail. But how free! And when they succeed, they do it on Google’s terms. They give their cut.

But of course Twitter is different, maybe totally. What makes this interesting is that it’s not clear the company knows exactly how. Nobody knows anything! The content people are platform naifs and the platform people are often content morons. This is not about asymmetry of vision or ability; it’s about overlapping interests amidst asymmetry of power — about a mutual realization that audiences are, for the moment, determined not only by geography or demography or subscription but by social networks’ pungent brew of all three. Twitter doesn’t know where this is going. If there is a master plan, it’s contingent on whether or not people like and use Moments in any sort of consistent way, and it’s subordinate to the master master plan, which also may not exist, for dealing with its own parent platforms, and for avoiding the bloated, boring fates of portals past.

For now, their only coherent message to the rest of us is this: Thank you for your service, it’s been really great. And don’t feel bad! It Not You. It Me.