Where You Came From

An American family, a racist letter, and feeling unwelcome in brown skin.

“This is something he always said would happen. And I always told him it wouldn’t, that we weren’t in Texas,” said Sarah Hernandez in her kitchen in Longmont, Colorado this past April.

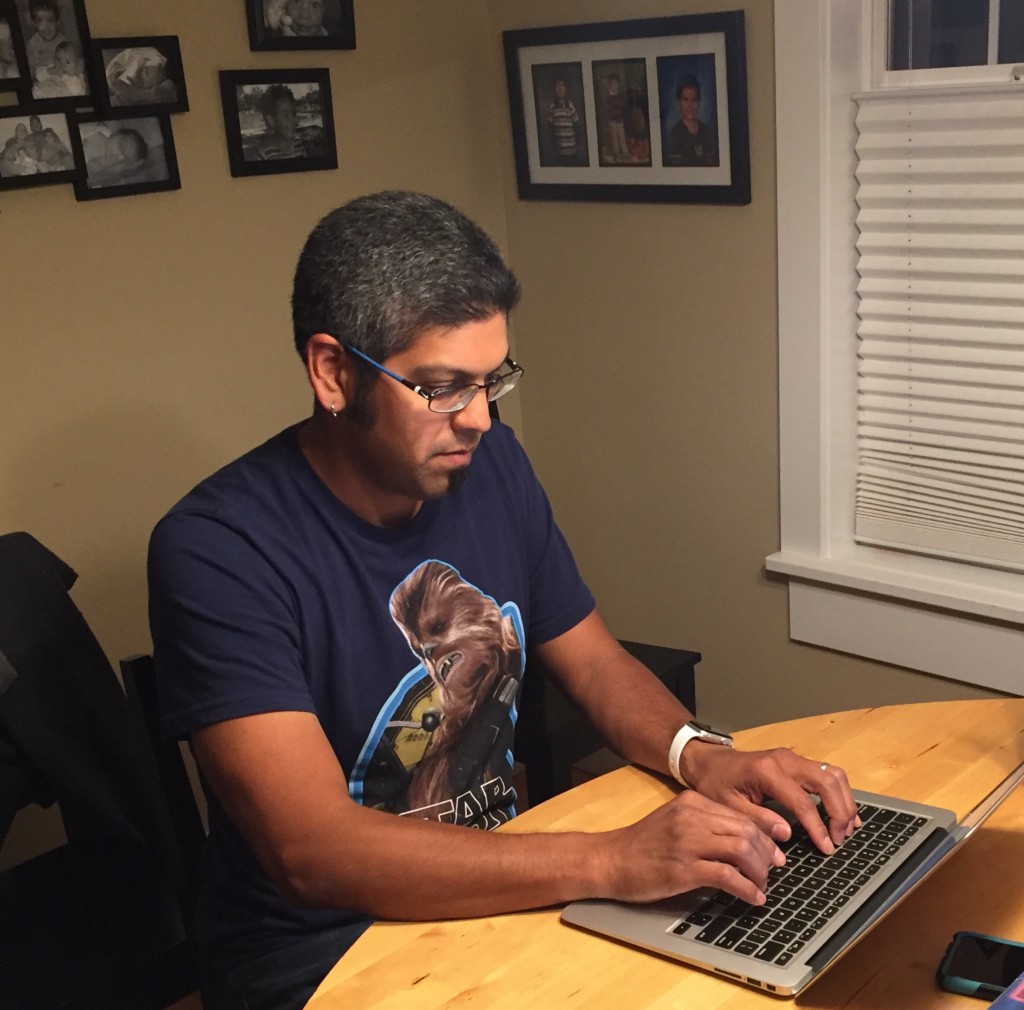

The previous Sunday, April 23, 2017, Sarah and her husband Daniel had been in Louisville, Kentucky for the VEX robotics world championship. Daniel is a computer science teacher at Westview Middle School in Longmont, Colorado, where he’s the coach of the robotics team. He’s also a Star Wars fan, who signs his emails: Danny “Vader” Hernandez.

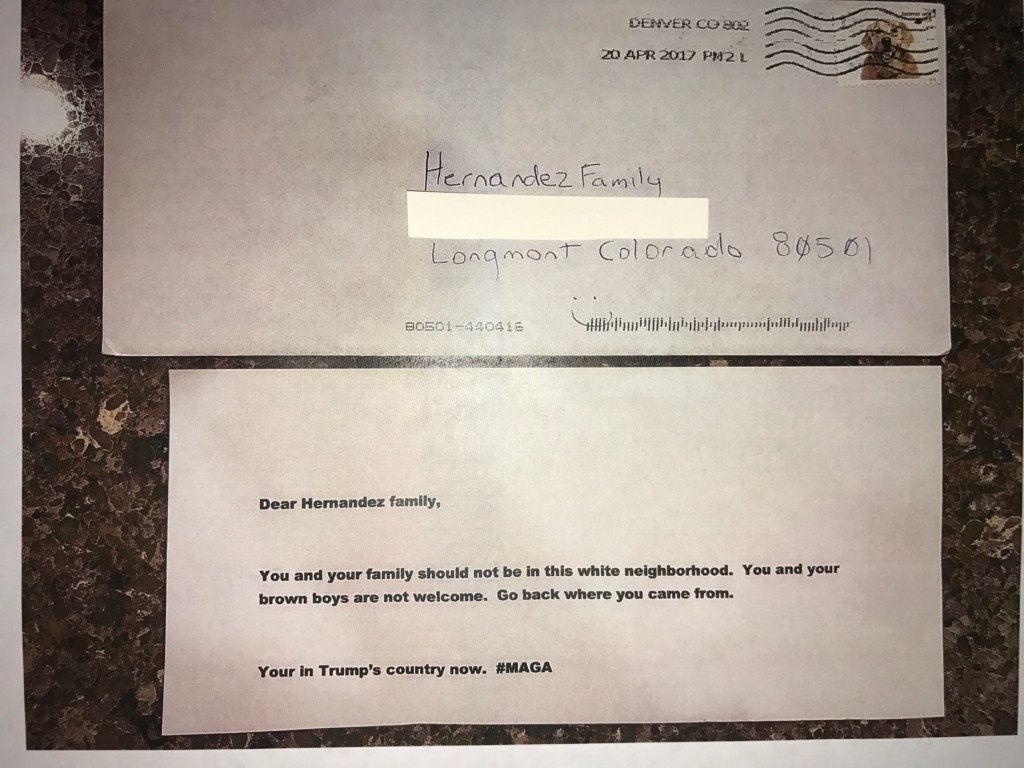

Danny and Sarah were in high spirits when they returned Wednesday evening; their team placed 4th. While she was going through the mail, Sarah came to a handwritten envelope with no return address. “I opened it, and I pulled out a half sheet. And I read it once, and I got cold. And then I read it again, and then I called him over…and then we sat down, and then we took some breaths, and I said, ‘I need my phone. We’re going to call the non-emergency [police line].’ And we did.”

Dear Hernandez family,

You and your family should not be in this white neighborhood. You and your brown boys are not welcome. Go back where you came from.

Your in Trump’s country now. #MAGA

Danny and Sarah met in 1997 at Baylor University, where Sarah, an athlete from California played on the school’s soccer team. Despite their affinity for each other, Danny immediately warned her that she would be the target of intolerance simply because she was dating someone who wasn’t also white. “He was like, ‘Are you sure?’” Sarah remembered. Danny shrugged in agreement. “We’d be a mixed-race [couple],” he said. For Sarah, the concern had never crossed her mind. To her, Danny looked like another southern California surfer boy. But Waco, Texas wasn’t Malibu.

For Sarah, this letter is further proof that Boulder County, Colorado isn’t either. This incident far surpassed the looks and the taunts they got at Baylor, and the rude comments they’ve heard since. For Sarah, it was a shock considering where they live — the Old Town neighborhood of Longmont, where yards sport signs that urge people to vote against fracking, and others that say “No matter where you are from, we’re glad you’re our neighbor” in three different languages. “Maybe it was a false sense of openness and open-mindedness. Maybe it’s the circle we run in. It’s a fairly liberal circle,” she offered. Then she added: “It’s a bubble.”

A reasonable first question would be, who sent the letter? It could have been anyone, a middle-aged racist; a younger, racist millennial. A man, perhaps. Or a woman. When the Hernandez family shared it on Facebook, many people questioned if it was even real. The Hernandezes told me they’re not surprised that people immediately doubt the story. Danny told me he’s been tailed multiple times at his local Bed Bath & Beyond by employees who believe he’s there to shoplift. Sarah said when she goes out with her kids, some people react with surprise or doubt that she’s their mother. “I’ve been asked if [their son] Luke is from Guatemala. ‘Oh, did you adopt him in Guatemala?’”

The Hernandezes are an all-American family. Danny, now 40, was born in Dallas, Texas. Sarah, now 39, was born in southern California. They have three boys, all born in Colorado. Sarah, who’s also a teacher, is white. Danny is, as the letter says: brown. But he was born and raised in Dallas. “I’m not going back to Dallas,” he quipped, and then he and Sarah delivered the punchline in unison, “it’s too fuckin’ hot.”

Danny’s mother, who is of Spanish and Mexican descent, was also born in the States, and his father is an immigrant from Mexico. “He came here legally with all his paperwork and everything, joined the Army. He did his stint with the U.S. Army and all of that, and then all the kids came along,” Danny said.

Danny’s father was a tailor and shoe repairman. The business was a success, so just before Danny was born, his parents relocated from a rough area in south Dallas to the more affluent but far less diverse Farmers Branch in the north Dallas metroplex. In elementary school, he was only of one of three non-white students, the other two were Asian and black. If he had hoped he would be less of an outsider when he entered middle school, he was wrong. Dallas was bussing students in from all over the city, so the middle school Danny went to was far more racially diverse, and significantly larger than his elementary school. But instead of finding companions in other Mexican-American students, they rejected him for being “too white.”

But he was too brown for the white students. They called him an enchilada, a burrito, a wetback. Danny’s way of dealing was to take their comments literally and turn it back on them. When they would call him an enchilada, he’d ask them if they meant the kind with cheese. When they’d call him a wetback and tell him to swim back where he came from, he’d tell them, “I’m pretty sure you’re not Native American. So your swim back to France or England is a much longer swim than mine. So you might want to get started.” It wasn’t until high school that things began to change. “It took a student who was not dark-skinned and who was popular to shut it down,” Danny explained. “It didn’t matter what I said,” Danny concluded. “It mattered what other people said.”

Danny developed into a skilled athlete, and the popular students came to his defense. People wanted to be his friend, and girls began approaching him. But he’d endured more than a decade of racist treatment from most of his schoolmates. “It’s like, ‘No. Now you want to be my friend? No. We’ve been together since grade school, and you’ve either contributed directly or indirectly’,” he told me. Even now, he opens Facebook to find friend requests from people he went to school with in Dallas. He doesn’t accept them. “That wound is deep,” he told me. “We’re not friends.”

Maybe it wasn’t a grown man or woman who sent the letter. Maybe it was a kid.

I met Daniel in Longmont, Colorado in 2013 when I was invited to join a neighborhood beer club. All the members live in or very near a tiny area on the west side of Longmont, Colorado known as “Old Town.” It’s about six long blocks north-south, and about ten short blocks east-west. Despite being such a small neighborhood, the beer club has about 30 members, and we’re all pretty close in age. It’s really just a bunch of thirty- and fortysomething dads with young kids and old houses that need something fixed. Sarah’s right: it’s a bit of a bubble.

Tom Vela is also in our beer club. He’s in his thirties, and he’s got two kids. His wife Liz teaches kindergarten at the same elementary school as Sarah. Liz, like Sarah, is white. Tom is half-Mexican, half-German. (Though, like Danny, he’s American-born.) Tom identifies as Mexican. He does, however, look white.

Tom’s experience has hardly been parallel to Danny’s. Where Danny’s family ran a successful business, and Danny excelled academically and athletically throughout all of his years of school, Tom’s family struggled. His father was a Vietnam vet and a firefighter, and then he left the family when Tom was eight. “We lost everything. We lost our house. We started moving place to place. For us to be able to make it, my brother and I started stealing food and those kinds of things… We felt abandoned. There was a lot of hate, and a lot of anger. We started getting into trouble.”

Money was tight, and at times non-existent. “I was in fourth grade, I think. I went behind one of the porn stores, and they threw out all their magazines. And I jumped in the dumpster, and I took all the ones I could remove, and I sold them at school. I just needed money… It was hard being really poor.” He shoplifted, too, but only necessities. “It was always food… I wanted bread…and tortillas are a very easy thing to slide right in front of your belly and walk out. And it’s a good, filling food.” Soon, Tom took up a more lucrative trade. “You make a lot more money selling drugs.”

It wasn’t drug dealing that got him into trouble, but fighting. After one particularly bad incident — a physical altercation with a teacher and police officer — he was arrested and expelled from school for half a year. This earned him a six-month stay in a juvenile detention facility. But there was one good thing: Tom took advantage of the counseling. “I was on the wrong path. I didn’t want to struggle my whole life. I definitely didn’t want to go back to a place like that, which was basically a jail or detention center… And I was headed down that path…either dead or in jail…” When he was released, he made up his schoolwork and tests, and managed to graduate on time. He continued to sell drugs out of necessity, but stopped as soon he was able, managing to never get caught for it.

Tom applied to college and was accepted. He enrolled in Colorado Mesa University, where he earned his BA, double-majoring in economics and finance. He then went on to Denver University, where he earned his master’s degree in organizational leadership. Tom’s now the vice treasurer of the Parent Teacher Association, chairman of Rocky Mountain PBS, and he’s a highly successful consultant. How many of the chances people took on Tom were because he looked white?

“I don’t know. It’s so hard for me to know. But I will say that I’m in an industry that is predominantly white male, and it doesn’t have a lot of Latinos. That says a lot. It’s a very small amount. Why is that? I don’t know. Could [my appearance] possibly play a factor, yes. A lot of people who get to know me see me as a white person. It may have provided me privileges. Definitely a likelihood,” Tom offered.

While Danny was being called a wetback, Tom had an entirely opposite experience growing up. He told me about the time he was playing with a new friend, a white kid. The boy assumed Tom was a safe person to be racist with. “All of a sudden, he just says to me, ‘Damn, I just can’t stand fucking Mexicans.’ And I looked at him, I’m like, ‘What?’ And he’s like, ‘Yeah, I fucking hate Mexicans.’ I mean, we’re like 9 years old, 10 years old. And I was like, ‘Why?!’ Like I didn’t even understand. ‘Oh they’re disgusting.’ And that’s when I said, ‘Well, I’m fucking Mexican,’ and we fought.”

The day after the November presidential election, a Latino woman — one of Danny’s fellow teachers — was waiting in line in a local donut shop when a white woman, also in line, said to her, “I hope your bags are packed because you’re not welcome here anymore.”

“I hope your bags are packed because you’re not welcome here anymore.”

“I think we are seeing more incidents,” said Stan Garnett, the Boulder County District Attorney for the State of Colorado. “A lot of these, as distasteful as they are, are not criminal. We’ve had several hateful letters mailed to the Jewish Community Center, to some other religious groups. And I think there has been more of that since the election.” I asked whether there were more of these incidents since Trump was elected, or if it was only just our awareness of them that’s increased. “My view is that there have been more, and there also have been more reported,” he said.

I asked Garnett why. “My view is that it’s a direct outgrowth of the nature of the rhetoric surrounding the 2016 election. My view is the United States is a country where racism and xenophobia have always at least simmered below the surface. I think the 2016 election unleashed some of that publicly,” he said.

The Hernandez family reported the letter to the local police, even though whoever sent the letter did not necessarily commit a crime. “Basically the First Amendment protects almost any public communication short of one that advocates immediate violence or rises to the level of harassment…It may be distasteful. But it’s not illegal.” And in this case, Garnett said he doesn’t think anyone’s committed a crime, and added, “if it’s not illegal, and this doesn’t appear to be, law enforcement should not be spending efforts trying to figure out who the person is.”

I asked Longmont Police Commander, Joel Post, why they were trying to identify the sender of the letter if it wasn’t a crime. He explained it was in case the Hernandez family experienced any more harassment. If there were any threats, they would view the Hernandez letter as a potential clue or evidence. In other words, it’s preemptive police work.

And just because someone sends a letter anonymously, doesn’t mean they have the right to stay that way. “[They] don’t have a right to anonymity. You have rights of privilege in the United States if you talk to a lawyer, talk to a priest, talk to a therapist. But you don’t have a right to be anonymous for this type of thing.” And as for “this type of thing,” Garnett didn’t mince his words. “There’s something incredibly chickenshit about somebody who states something, particularly something hateful, and is too scared to sign it.”

As of this time, Commander Post said he has no word on how far along they are in their investigation into who sent the letter.

I interviewed Danny and Sarah in their kitchen, where the island was overflowing with flowers sent to them by friends and neighbors. Whenever I’ve seen Danny in the last four years, he’s always joking about something, and there’s always enthusiasm in his voice, whether he’s talking about his kids, robotics, baseball, beer, or Star Wars. But as I sat across from him and Sarah, Danny was a mix of stoic and angry. I was surprised by how little he said. When he did speak, his words were witheringly angry. Gesturing to the flowers all of his friends had sent them over the previous few days, he said, “Now I just have a bunch of flowers to water.”

Danny is not only angry about what happened, but I also see that he’s exhausted. At one point, he tells me “The terms used in this note, that’s not a first for me.”

For him, it seems, the damage is already done. But for their kids, it’s not. They’ve been growing up in the same protective, progressive bubble Sarah and Danny have been in since they moved to Longmont. They go to the elementary school in the same neighborhood where they live, and where their mom teaches. The other children don’t know them as “brown boys.” They know them as neighborhood kids whose mom teaches at the school they go to. In fact, they’ve been so shielded from discrimination, Sarah told me that they’re not even all that aware of their race, or how it differs from anyone else’s. “Benny and Andy, it’s kind of the same thing — they’re not aware,” Sarah explained, then added, “Luke once said he thought he’s white. We were like, ‘buddy, you’re both.’” So now their main concern is this: how will they be treated in school by kids who they haven’t grown up down the street from?

Danny is widely known as a favorite teacher, a coach, and a fun dad. Sarah is known as one of the most cherished teachers, too. She plays soccer and enjoys craft beer. They are at every picnic, barbecue, party in the neighborhood. They are power couple of suburban, middle-class goodness. A non-profit called Showing Up For Racial Justice shared the incident on their social media accounts, while a Longmont Bike Night was held in honor of the Hernandez family. When the local paper, the Longmont Times-Call, covered it, they called the Hernandezes a “Historic Westside family.” But how much does that really matter? That the Hernandezes are a “good” or “upstanding” family has no bearing on how disgusting the letter is.

What their status as a family has afforded them, though, is the support and confidence to be able to speak out about what they’ve experienced. “I don’t know how isolated [this incident] is,” Stan Garnett told me. “The experience of being undocumented in the United States for most people is a very, very lonely experience. When you talk to members of the undocumented community, the thing you hear more than anything else is how isolated and lonely they feel. When there is an incident like this, it has a real impact on the sense of security and well-being of the undocumented community.” He continued: “This family who experienced this and felt confident to reach out is great. There’s a lot of people who experience things like this who are afraid to tell anyone about it.”

There is a gap between what actually happens and what we think happens. The gap that reveals itself when something like this happens in, of all places, Boulder County, known as much for its progressive politics as its craft breweries. When Danny posted the letter on Facebook, people left comments, aghast, expressing their disbelief that such an awful thing could have ever happened. It’s that disbelief that Danny thinks that’s part of the problem. About everyone who’s been so blindsided, Danny asked rhetorically, and with a good dose of frustration: “How can you not know this can happen?” Then his voice softened, and he said, “But if you’ve never had to live it or experience it or be around it, I guess in some ways, how would you know it’s happening?”