Privacy: The Sequel

One thing that makes caring about tech privacy issues difficult is that rather than getting solved, they often just get replaced with bigger ones. Mounting a fight against red light or speed cameras might slow their adoption, or get a few taken down, or win some lasting protections against overuse of the data they produce. Then, a few years later, the terms of that discussion are overtaken by the availability of high altitude drone-mounted cameras that constantly photograph entire cities, allowing every car to be tracked constantly. Using credit cards meant accepting the paper trail they produce behind your daily spending; now, your cellphone company — as well the companies that make software for your phone — knows where you are at all times. In 2005, the NSA wiretapping phones without warrants was a shocking scoop. In 2013, we found out the NSA had everything. Ten years ago, Google placing ads in Gmail was seen as an egregious violation of email privacy. Today, Google Now reads your email to tell you when your flight is going to leave, and what time to leave your house, which it can show you in photographs taken from space or from the street out front. The surveillance state is great at confirming our worst vague fears. In consumer tech, the arc of privacy bends toward “well, I’m using this anyway.”

Earlier this month, as our long national conversation about ad blocking and tracking was just heating up, Nautilus published a story titled “What Searchable Speech Will Do To You,” which made a convincing case for the urgency of the following question: “Will recording every spoken word help or hurt us?” The implication, of course, is that the recording is going to happen no matter what.

If yesterday’s unease about privacy seems quaint by today’s standards, and if tomorrow’s will have the same effect, the privacy issue becomes both more pressing and less approachable. These are the conditions that create cynicism and despair. They suggest not just that “privacy” is a lost cause — as Google’s Eric Schmidt clumsily attempted to explain in 2009.

They present, against all-consuming inevitability, one solution for continued sanity: a redefinition of the concept. Which brings me to this remarkable document from the Brookings Institution: “The privacy paradox: The privacy benefits of privacy threats,” by Benjamin Wittes and Jodie C. Liu:

In this paper, we want to advance a simple thesis that will be far more controversial than it should be: the American and inter- national debates over privacy keep score very badly and in a fashion gravely biased towards overstating the negative privacy impacts of new technologies relative to their privacy benefits.

This is an argument that challenges not just the loss-of-privacy tech narrative but one of the premises that has produced it — the “default assumption” that “as technology develops, the capacity to surveil develops with it, as do concentrations of data — and that such capacities and data concentrations are inimical to privacy values.” This, the paper suggests, is an insufficient account of technological change.

Perhaps the lowest hanging example is Google. It’s a service patronized by most of the internet-using public, and has gathered an unprecedented amount of information about the humans of the world. The Google search box functions as place to look for help and to confess.

Target Manhattan location open hours

precedes painful

urination cause

right before

how to tell if im depressed

Together, these searches create a worryingly intimate profile — one that arguably overrepresents your most sensitive online activities. A profile that belongs to a multi-billion-dollar advertising company. A profile associated with your real name, email, location information, and chats.

But! But. But. What about all the things Google allows you to find, or do, that would have required either risky or impossible behaviors elsewhere? A small-town teen can seek medical information without going to the doctor, who might know her parents. The acquisition of porn, the paper points out, now happens at home, rather than at the magazine rack or the video store. The authors’ broader diagnosis:

The result is a ledger in which we worry obsessively about the possibility that users’ internet searches can be tracked, without considering the privacy benefits that accrue to users because of the underlying ability in the first instance to acquire sensitive material without facing another human, without asking permission, and without being judged by the people around us.

Consider an older technology in these terms:

Create phone lines for the first time and you create the possibility of remote verbal communication, the ability to have a sensitive conversation with your mother or uncle or lawyer from a distance. It is only against the baseline of that privacy gain that you can measure the loss of privacy associated with the sudden possibility of wiretapping.

I can’t stop thinking about this paper. Not that I find it totally persuasive! Its central worry seems to be that our “ledger” or, later, “roster” of technology’s privacy impacts is faulty, or doesn’t fairly represent the semi-related privacy boons we enjoy thanks to some of the most powerful companies in the world, which is a problem for… those companies? Facebook gathers data and makes money from it. Facebook allows people to communicate with each other individually or in groups, out of sight or in full view. It’s not clear to me why these two facts, which pose very different questions about power and control, must be placed on one scale of good and harm, and rendered in its units.

What do we gain, exactly, by cramming so much meaning into the concept of privacy that it better conforms to our economy’s self-perpetuating concept of progress? It’s less clarity than comfort. The paper came out shortly before the Ashley Madison hack, which is fun to analyze through its lens. Ashley Madison was the ultimate privacy-enhancing service, until it wasn’t.

But the paper’s authors are aware of the boldness of their claims — they understand, I think, that making such a counterintuitive argument, and one that might be accused of merely rationalizing of power, demands a little humility:

The key point here is not that big data does not have some, maybe many, negative consequences for privacy — some of them quite severe. It does, and we are not trying to argue that the privacy literature errs in drawing attention to those negative impacts.

It is a question, instead, of “types” of privacy and proportion. But the reason I can’t stop thinking about this paper is because of how I imagine its ideas might be deployed, or selectively represented (or simply arrived-at by actors with a real stake in the definition of privacy). It doesn’t take much imagination to see some major privacy questions arriving ever more quickly. Both Android and the iPhone listen for voice commands at all times; Apple is getting into healthcare as it sells its first wearable; wearables in general are guaranteed to become more powerful, cheaper, and less burdensome. Companies will be making some huge asks, or just making equivalent assumptions: think about the data required to enable predictive shopping. What about the first device that promises total speech recall? The rise of a dominant, consumer-facing health records company? An actual convergence of the comically fragmented Internet of Things? Companies may need to present alongside their new products a method for staying sane — a new framework for consumption; or a misdirection; or, depending, a polite lie–and I think it might sound something like this paper, minus the caveats, and in far fewer words.

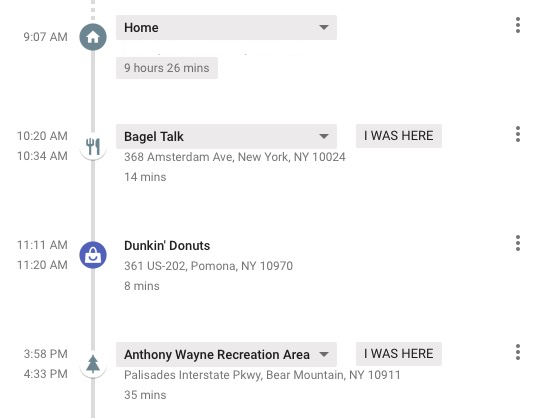

I came across this paper because it was approvingly shared on Twitter by a venture capitalist — an interesting observation, some food for thought. But it’s plausible, I think, that the argument for the redefinition of privacy — not this paper’s, but a definition like it–is assured no matter what. It may never need to be articulated by Amazon, or Google, or Facebook. In fact, doing so would be suspicious and distracting. It will instead be cobbled together after the fact, and only to meet the low demands of the user’s rationalization to self. This seems to be what’s happening reliably now, already. Remember the The Xbox One’s always-on Kinect camera? Amazon’s always-listening Echo device? FourSquare changing from a service that lets you “check in” to a service that asks you to review, automatically, places it can tell you’ve been? Google Maps, in addition to being a service you ask for directions, becoming a log of places you’ve been, whether or not you’ve searched for them? When these amounted to controversy it was forgotten almost immediately.

It doesn’t seem very useful to reassess our ledgers of privacy without also considering our ledgers of power. Those companies that have invited the most criticism for their erosion of privacy have become vastly more powerful than the people doing the complaining. The alleged surplus of “obsessive” worry didn’t do much to stop that; stories like this one, from 1990, which concludes that we have “no way of knowing all the databases that contain information about us” and that “we are losing control over the information about ourselves,” don’t seem pathetic or wrong-minded in retrospect. Mostly just ill-equipped.

In this new world, the old privacy is discarded with for its lack of utility and its interference with ubiquitous and fundamentally incompatible services. In which case this paper is less a guide than a preview of an environment in which today’s privacy concerns seem impossibly minor — and in which their champions are gradually marginalized. It’s an argument, in other words, that may never need to be made, because it will make itself.